ArchBook: Architectures of the Book

Published 5 December 2013

Corrected and updated 28 February 2022

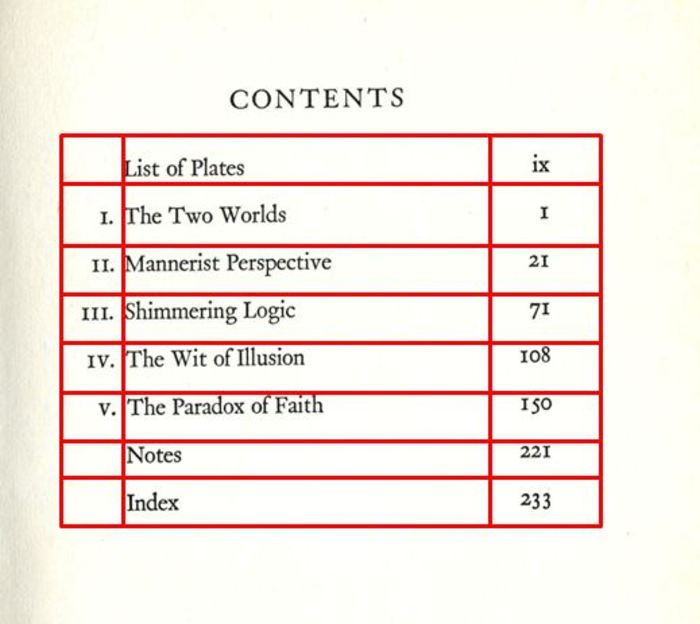

Figure 1

Click For Larger Image

Table of ContentsA typical modern representation of contents in a tabular form. From Murray Roston's The Soul of Wit: a Study of John Donne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974). CLOSE or ESC

A “Table of Contents,” or sometimes simply “Contents,” is a sequenced list of the divisions of a book, most commonly the chapters. It typically provides a division number and title correlated with the first page number of that division. In most English publications, the table of contents is located in front of the elements that it itemizes, after the title page and notice of copyright; but in French publications, for example, it is commonly placed at the end of the book. The page numbers for the preliminaries, or “front matter” (list of illustrations, acknowledgements, list of abbreviations, sometimes the preface), are typically indicated in lower-case Roman numerals, and the principal content (introduction, chapters) and back matter (appendices, notes, bibliography, indices) are indicated in Arabic numerals. The chapter and section headings are represented as they appear at the head of each section, so that the table of contents is directly determined by the explicit structure of the book (fig.1). If the book is a collection of essays by individual authors, for example, the table of contents will typically include the author’s name in addition to the title of the essay. The table of contents is similar to an outline, except that by convention one expects a heading in an outline to communicate something of the content of its section, and this is not always the case with a table of contents: in its simplest form, the table of contents simply reiterates the headings of each chapter as found within the book, and these might not be indicative of the chapter’s content. Chapters, for example, might be titled merely by number (“Chapter One,” “Chapter Two,” etc.). Like an index, the table of contents directs the reader to elements of content, but unlike an index, it indicates the starting points of significant structural breaks, while the index specifies locations where particular topics are addressed. An early precursor of the table of contents, adopted in the third century to aid biblical scholarship, was indeed something much more resembling an index: a list of topic summaries pointing to instances within the biblical text, rather than simply indicating the beginning of each book of the bible.1 The index and table of contents continued to develop in parallel, but over time their functionality became distinct. While they shared a locative function, the table of contents came to represent the content of the book with reference to its structural divisions and to point the reader to the beginning of those divisions. The index developed a more granular representation of the book’s content, pointing to particular instances in a book where certain kinds of content could be found, such as subjects and topics, people, and places.2

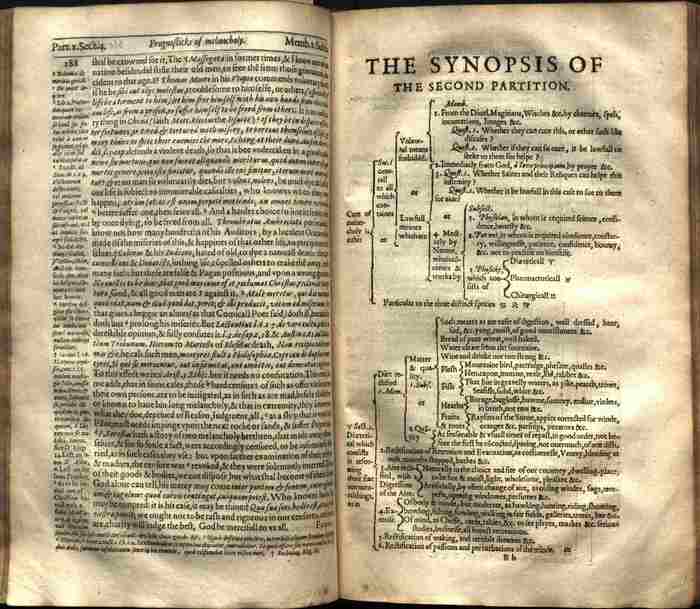

Figure 2

Click For Larger Image

Synoptic DiagramA synoptic diagram from Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy. Image courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

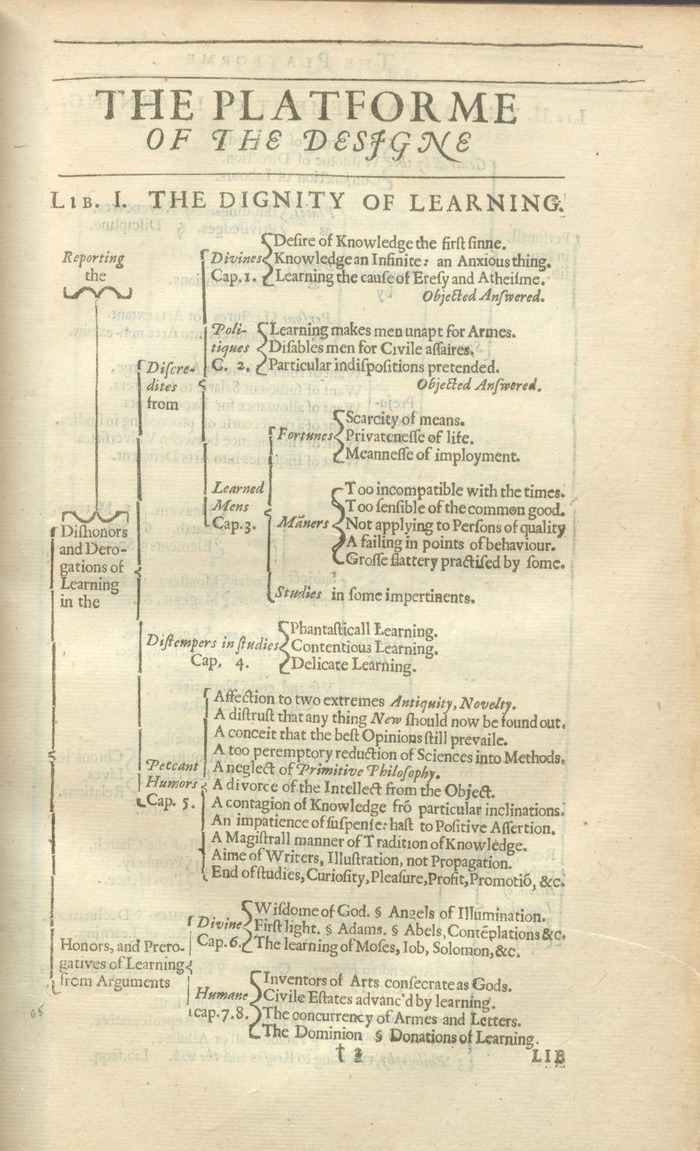

The term table suggests a very particular formal arrangement of information, but as the representation of contents varies in complexity and granularity, so does it in form. In Latin, a tabula could refer to a writing surface or a writing generally, or specifically to a record of accounts that, implicitly, took the form we associate with a table of elements, as in a list of names associated with amounts owing or receivable; or it could simply refer to an illustrated panel or picture. The tabular form for representing content has precedents in manuscript culture. Eusebius (c.260-339 CE), for example, devised a system for identifying and navigating between parallel passages in the Gospels by breaking them into numbered sections (marked in the margins of the text), then correlating these numbers in columns to indicate passages that any four, three, or two of the Gospels had in common.3 Thus Eusebius’s canon table, which became a popular feature in New Testament manuscripts, often elaborately and ornately depicted, was a tabula in two senses: a visual illustration of content that displayed its information in columns and rows. Representations of contents do not always take a tabular form. In early printed books, elaborate title pages and frontispieces often provided detailed accounts of the contents of the book. Tables of contents often work in concert with other navigational devices. In some Bibles, for example, tabs fastened to the edge of the page mark the start of the individual books, so that with an overview of the entire contents in mind, the reader can quickly locate a particular book by looking along the right edge of the Bible without having to flip through pages to find a particular page number. Similarly, running titles Running-Title a repetition of the title at the top of every page above the normal text block. Also called "running-head." See: Headline CLOSE or ESC can be seen as an extension of the table of contents, identifying in the header the section of content on that page. Synoptic tree diagrams were another means of representing content in a relational and discursive rather than structural form, though they often sought to represent the totality of a work purely in terms of intellectual categories and relations, rather than structural ones (fig. 2).4

As an element of paratext Paratext material included in a book or other textual form that is not considered part of the "main" text; e.g. title pages, tables of contents, prefatory letters, advertisements, indices, etc. See: Preliminary Leaves CLOSE or ESC, the table of contents is a threshold to the main body of the text, “announcing” the contents and giving readers opportunity to strategize their approach to the book.5 The primary function of the table of contents is to enable navigation of a book’s content by locating major structural breaks in the text. Insofar as the heading of each section is representative of its content, the table of contents also serves as a kind of summary, giving a brief overview of the broad topics to be discussed. Insofar as the chapter titles represent what the chapters contain, the table of contents also provides a particular conceptualization of the book’s contents.

It is difficult to pinpoint the origin of the table of contents. Before the widespread adoption of the codex Codex a book format made of stacked leaves that are attached together along one edge. See: Binding Edge Format Leaf CLOSE or ESC, labels or tags of clay were sometimes attached to scroll containers to indicate contents,6 and individual scrolls often had markers to indicate the locations of particular content, but a register of contents did not become standard until it was implemented in the codex. Even in the early stage of the codex, the table of contents was uncommon. One of the first references to a table of contents is by Pliny the elder (23-79 CE) in his dedicatory preface addressed to Vespasian Caesar, where he credits Valerius Soranus’s (d. 82 BCE) Epoptides (Lady Initiates) as the predecessor of his own implementation of a table of contents (contineretur libris) for the thirty-seven books of his Natural History. Pliny tells his dedicatee, Vespasian, that he provides this reading device in consideration of the considerable claims upon the emperor’s valuable time, so that he won’t have to read all thirty-seven books in their entirety. He then describes more generally its functionality for readers, who “by these means will . . . not need to read right through them either, but only look for the particular point that each of them wants, and [they] will know where to find it.”7 Indications of contents were used sporadically in late medieval manuscripts and quickly became standard in the printed book. The earliest instances in manuscript were title lists of discrete works bound together into a single codex,8 or sometimes simple lists of chapters of a single work.9

In the cathedral schools of Europe in the middle ages, where bible education was conducted on a shorter timetable than in the monasteries, study aids became the starting point for study, rather than the scriptures themselves. Thus there was a need for students to be able to locate more efficiently passages in the biblical text identified in the commentaries and epitomes they were using. As a consequence, the table of contents became a common fixture of bibles by the middle of the 12th century, serving not simply to summarize the contents of a book, but to aid the reader in locating its major divisions. At this time, location of these divisions typically depended on highlighting techniques used to mark the beginning of each division (capital letters, marginal titles, etc.), rather than the use of page numbers.10 By the late middle ages, the table of contents had become an integral part of book production in all domains.11 More fulsome, synoptic tables of contents providing chapter summaries were commonly used for patristic texts, and detailed tables of contents, or “kalendars,” were devised for professional texts.12 In the early days of print, the table of contents was “foreshadowed by a printed 'register' which in a great many cases was merely a printed list of the first words of the sheets or gatherings in a book, intended mainly to guide the binder in putting the book together correctly.”13 Insofar as the listed divisions coincided with structural divisions in the text, such a register could serve a basic locative function. Precise location improved with the widespread adoption of pagination Pagination the numbering of pages. See: Foliation Page CLOSE or ESC in the sixteenth century.

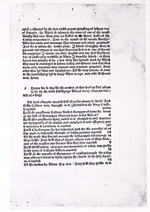

Figure 3

Click For Larger Image

William CaxtonCaxton's printing of Godfrey of Boloyne's conquest of the holy londe of Iherusalem (1481). Image courtesy of The Huntington Library.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 4

Click For Larger Image

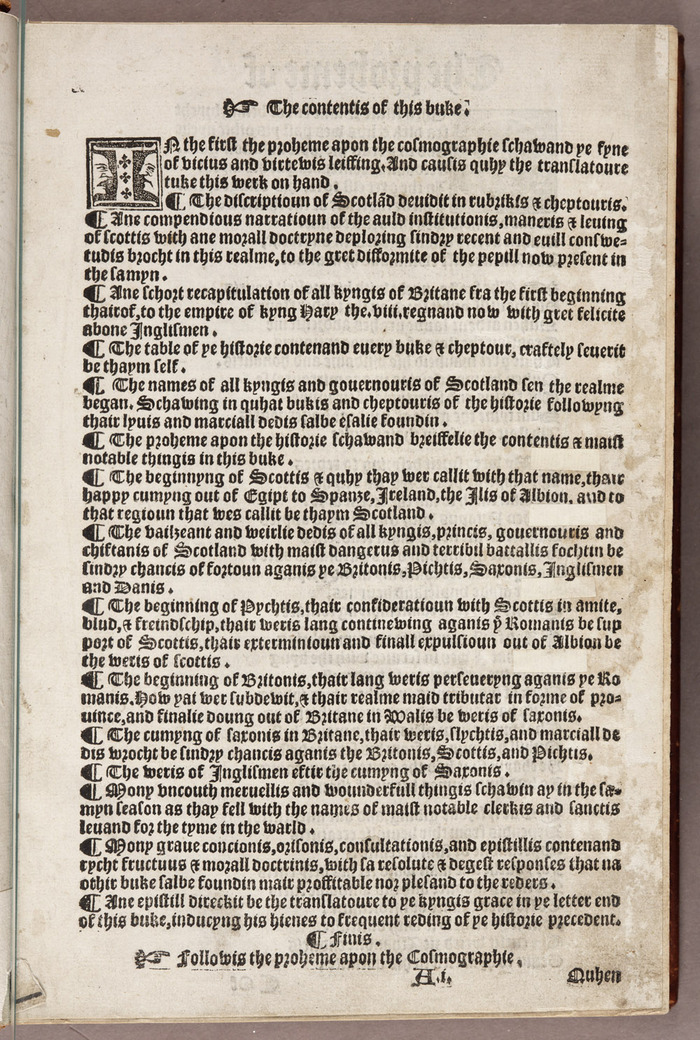

Hector BoeceHector Boece's Scotorum Historiae (c1540). Image courtesy of The Huntington Library.CLOSE or ESC

The first self-identifying table of contents printed in England is in Caxton’s printing of Godfrey of Boloyne’s Conquest of the holy londe of Iherusalem (1481).14 Caxton’s heading declares both its form and its function: “Thenne for to knowe the content of this book, ye shal playnly see by the table folowynge wherof euery chapytre treateth al alonge” ([a4], fig. 3). Indeed, the chapters are neatly summarized and keyed to the chapter number, although corresponding page numbers are not provided. These summaries and numbers are reproduced at the head of each of the short chapters, so it is easy to navigate the book using the table of contents despite the lack of page numbers. Another, though less successful, early print example of what we recognize as a proper table of contents is Hector Boece’s Scotorum Historiae (c. 1540).15 Like Caxton’s it provides brief chapter summaries, but it lacks chapter numbers as well as page numbers, and the wording of the chapter headings is often very different than what is provided in the table of contents, making it much more difficult to navigate (fig. 4). These early representations of contents were relatively simple, and more recently, in the last hundred years or so, simplicity of form has again become standard (see fig. 1); but in the early modern period, as print architectures matured, the table of contents became increasingly complex.

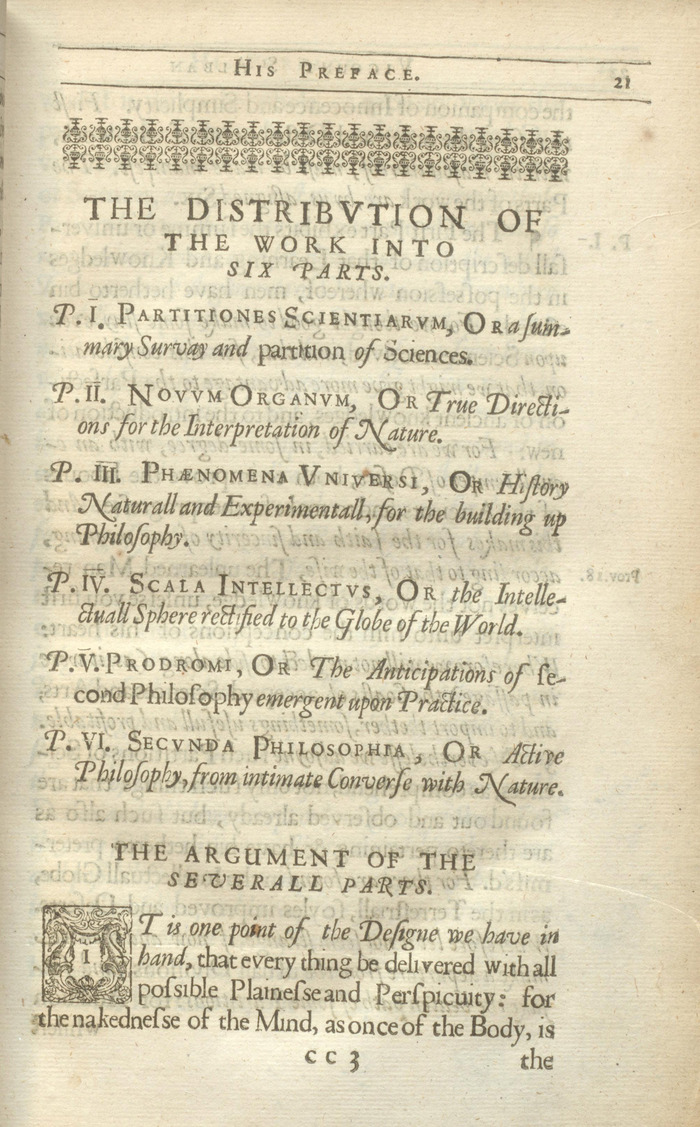

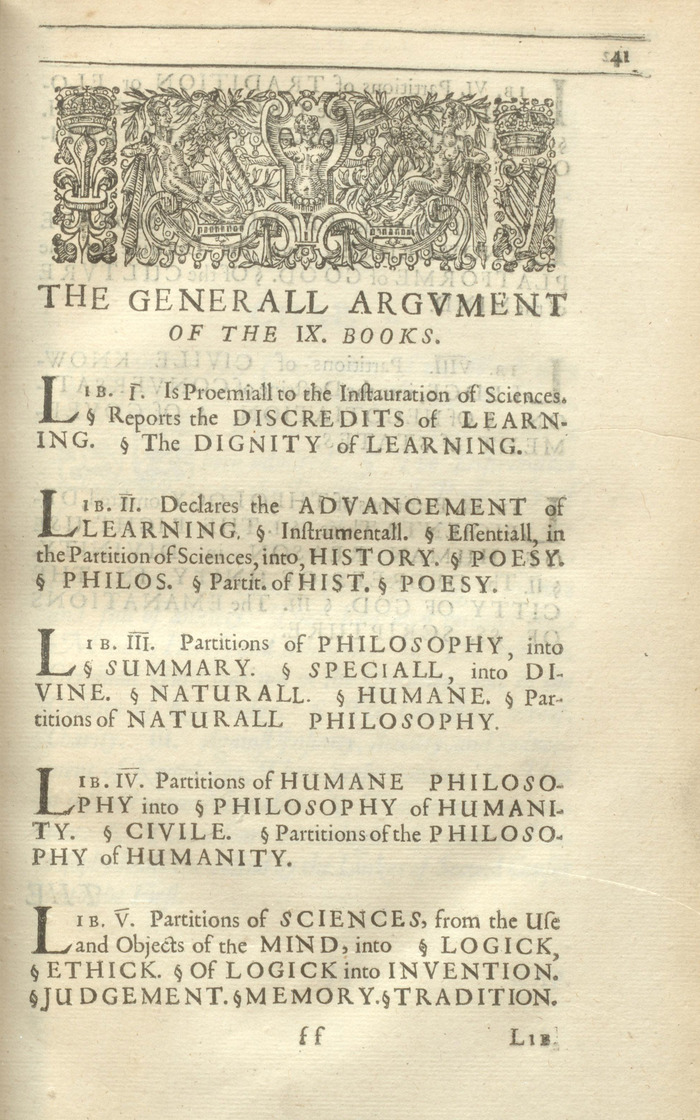

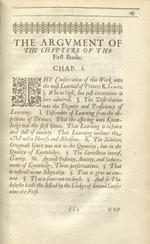

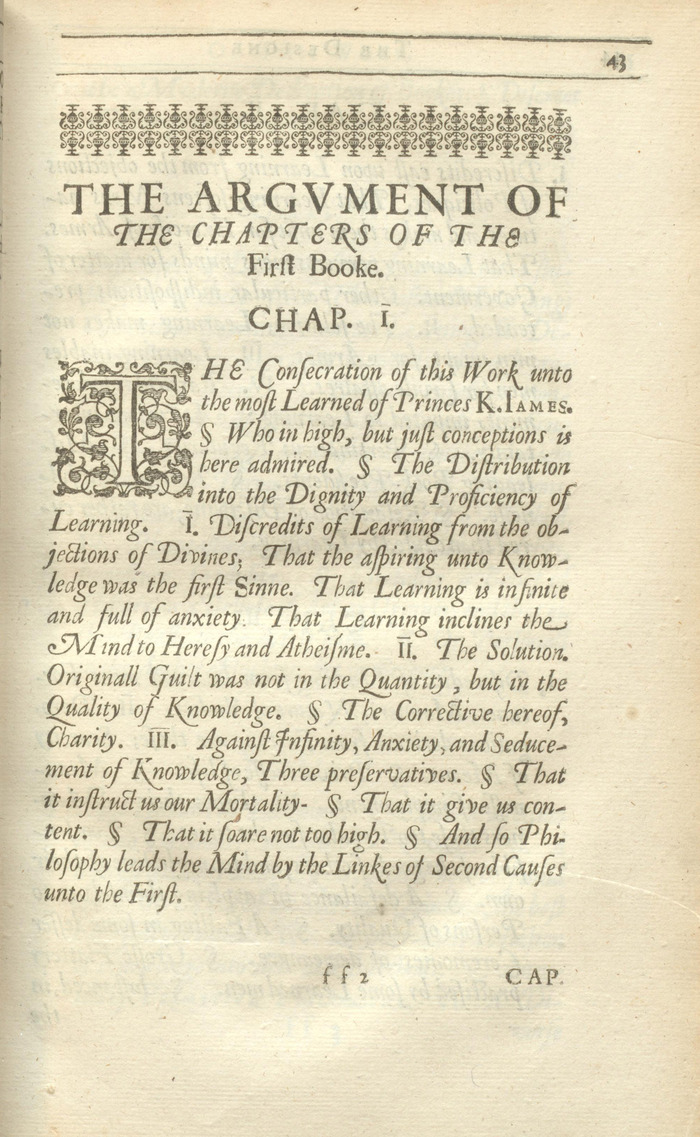

An extreme example is Francis Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning; or, the Partitions of Sciences (1640).16 This was the first installment in a projected six-part project, his “Great Instauration of Learning,” of which only two parts were ever (provisionally) completed. All four extant editions of the Advancement (1605, 1629, 1633, and 1640) are substantially the same in the main body of content, but the fourth of these provides considerably more, one could even say extensive, preliminary material: over a hundred pages of it in a book that totaled around 550 pages. A significant portion of these preliminaries is navigational superstructure, much of which can be considered some variation, elaboration, or reiteration of a table of contents. First, “The Distribution of the Work into Six Partes” outlines the whole Instauration, only the first item of which indicates the current text: “Partitiones Scientiarum,” or Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning (fig. 5). This is a bird’s-eye, conceptual overview of the whole projected work on a single page. What follows, starting at the bottom of the same page, is an elaboration of this table of contents, summarizing the “argument” of each of the six parts, running to twenty pages (fig. 5). Then there is a brief representation of the “General Argument,” i.e. the content of the present volume (the first part of six in the larger project). Here the “argument” takes the form of an outline, itemizing the general content of each book and providing a few subsidiary topics for each (fig. 6). This takes a page and a half. Then we get a reiterated, fuller version setting out in advance the argument of each chapter of each of the nine books, with elaboration, giving a more particularized version of what came before (fig. 7). This runs to eighteen pages. Moving through these “preliminaries,” the reader drills down further and further into the content that will be provided in full within the body of the book. Complementary to these outline representations of content is a series of synoptic diagrams, one for each book, one per page. Rather than representing the major structural breaks of the text, these present a visualized rationalization of the main concepts of the book, focusing not so much on sequential arrangement as on conceptual-hierarchical relationships (fig. 8). (See fig. 2 for the synoptic diagram). In some of its more elaborate manifestations, the table of contents thus provides a conceptual representation of the book’s intellectual content. In the case of the 1640 edition of Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning, the reader can correlate high-level categories with more particular concepts. The various levels of representation give increasingly specific access to highly and explicitly structured material of the book.

Figure 5

Click For Larger Image

"The Distribution of the Work into Six Partes"in Francis Bacon's Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning; or, the Partitions of Sciences (1640). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 6

Click For Larger Image

"The General Argument"in Francis Bacon's Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning; or, the Partitions of Sciences (1640). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 7

Click For Larger Image

"The Argument of the Chapters"in Francis Bacon's Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning; or, the Partitions of Sciences (1640). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 8

Click For Larger Image

Synoptic diagram or "The Platforme of the Designe"in Francis Bacon's Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning; or, the Partitions of Sciences (1640). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

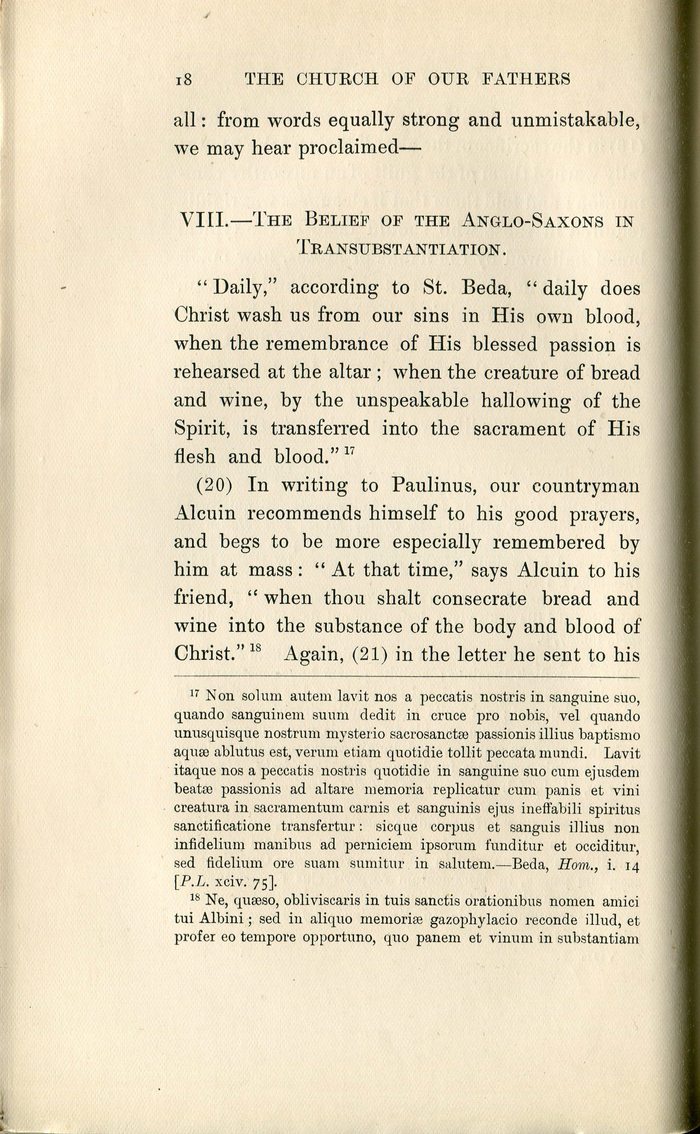

Figure 9

Click For Larger Image

Section on "The belief of the Anglo-Saxons in Transubstantiation"in Daniel Rock's The Church of Our Fathers (1905). CLOSE or ESC

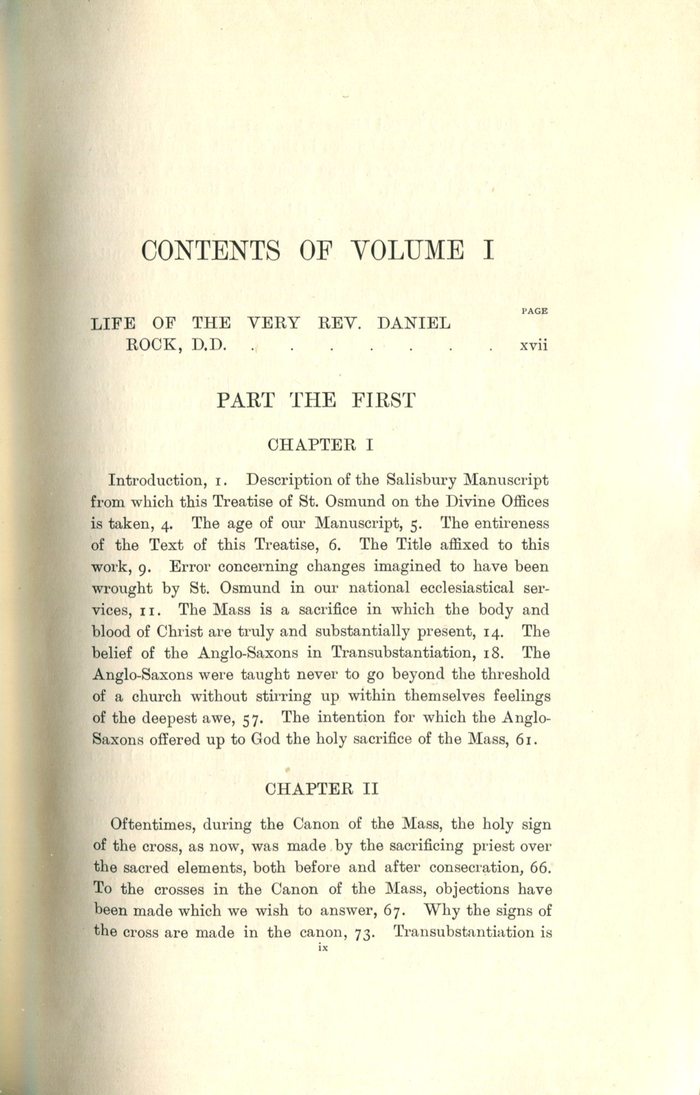

Figure 10

Click For Larger Image

Detail "Contents" for Part one, Chapter onein Daniel Rock's The Church of Our Fathers (1905). CLOSE or ESC

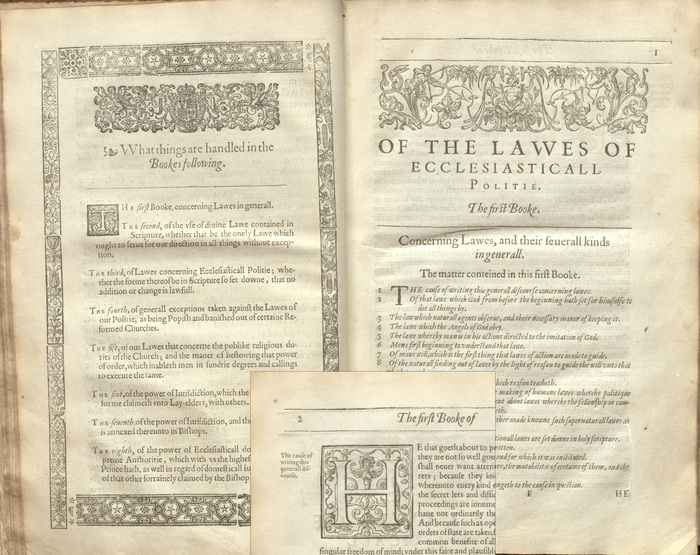

By the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, books of serious non-fiction often represented their contents with fulsome and elaborate descriptions and location aids for surveying and navigating its contents. The second edition of Daniel Rock’s The Church of Our Fathers (1905), for example, provides a summary of the main points of content in each chapter, keyed by reference number to the relevant location in the text.17 On the first page of the “Contents,” for example, one gets a detailed itemization of the nine major topics discussed; these are numbered as section headings in chapter one (fig. 9), comprising a fairly granular account of its contents. Supplied with the “part” number (“THE FIRST”), the chapter number (“1”), and the page number (“18”), one can locate not only where the chapter begins, but also the page on which Rock discusses, for example, “The belief of the Anglo-Saxons in Transubstantiation” (fig. 10). The header of the page indicates the page number, of course, but also, on the recto, the part and chapter number, correlating with the table of contents to provide structural context. The people responsible for the publication of this book were clearly considerate of those who would use it. In addition to these aids in summarizing, locating, and conceptualizing the content of this particular edition, they also provided in parentheses the numbered page breaks of the original edition. For example, on page 18 of the present edition, the beginning of pages 20 and 21 in the previous edition are marked as “(20)” and “(21)” respectively (fig. 9). An earlier instance of a granular representation of contents that serves also as structural markers is Richard Hooker’s Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (1611).18 In this case, a second, summary representation of contents is provided for each chapter, and these summaries then serve as marginal headings to mark each sub-section (fig. 11).

Figure 11

Click For Larger Image

Representation of contents, with inset detail, in Richard Hooker's Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity (1611). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

In the present incunable period of the Web, the table of contents remains a vestige in many online publications, especially in cases where the content of a site is essentially that of a traditional book. The TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) Guidelines, for example, are conceived as a monograph and thus are represented online in a table of contents.19 The chief point of difference between print and Web is that page references are replaced by hyperlinks to the indicated content. While the table of contents persists as residue of print culture, the native form for representing content structure in the Web environment is the menu. Unlike the monograph-based representation of “contents,” the menu typically represents classes or kinds of content, rather than summarized depictions of particular sections. The menu along the top of the page for the TEI guidelines, for example, represents the categories of information provided across the whole TEI site: “Home”; “Guidelines”; “Activities”; “Tools”; “Membership”; “Support”; etc. A typical Website is a repository of disparate but related information, rather than a unified composition, and thus requires a different form and structure for representing its contents.

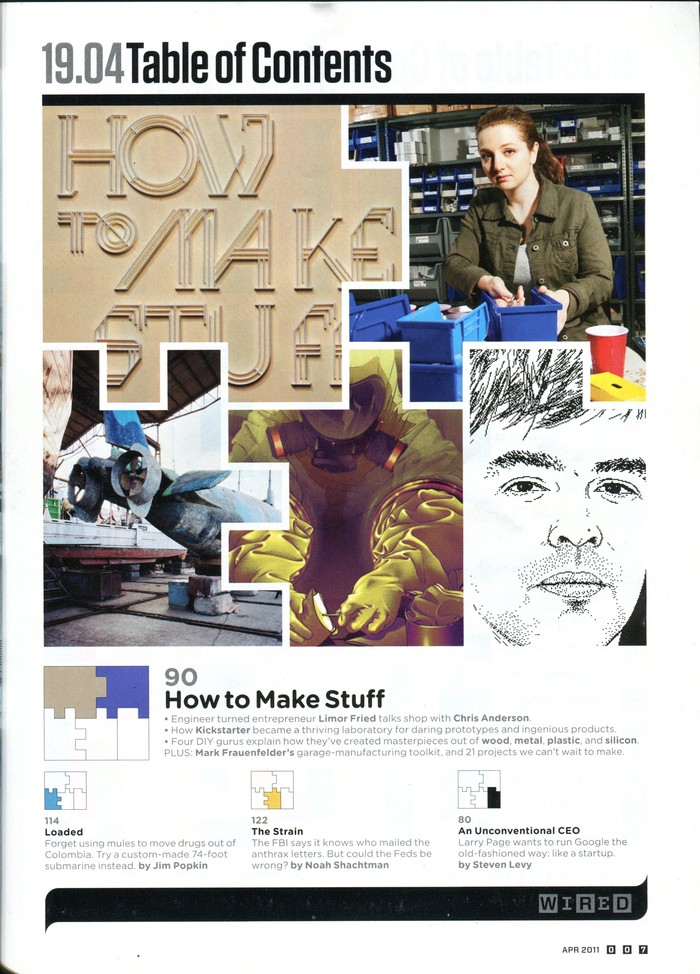

Wired Magazine: from print to digital representation of contents

Figure 12

Click For Larger Image

The first Table of Contents (of the main features)in the print version of Wired 19.04 (Apr 2011) CLOSE or ESC

Figure 13

Click For Larger Image

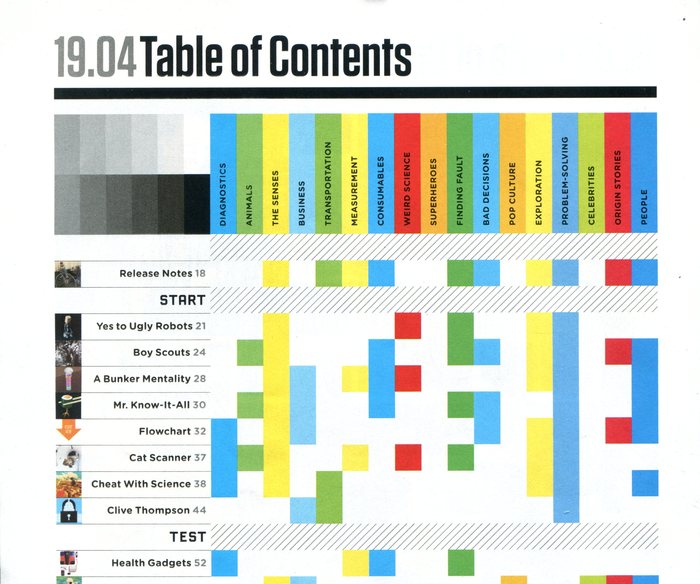

The second Table of Contents (the regular departments)in the print version of Wired 19.04 (Apr 2011) CLOSE or ESC

As is almost always the case in transition from one medium to another, developments in book architecture on the Web have not been uniformly progressive and linear. In most cases, the form of the Web-delivered book precisely mirrors that of print, and so the table of contents remains unchanged. In other instances, representations of contents take on entirely different forms. In some cases, these new forms fall short of the functionality that has been achieved. in print. Although it is not a book per se, Wired magazine is a revealing example of such a case. The 19.04 issue (April 2011) of the print edition provides two “Table[s] of Contents” that, together, provide all the functionality described above, and does so using innovative forms. The first focuses on the four feature articles in the issue, which comprise the back half of the magazine (fig. 12). The top two thirds of the page represent these features pictorially as pieces in a puzzle. The bottom third of the page correlates these images with small schematic diagrams of the same puzzle, colour-coding individual pieces to correlate with the relative piece in the pictorial puzzle above. Each “piece” takes the place of the serial number that is common in the table of contents, and each corresponds to a prose representation of its featured article, providing a title, brief summary, byline, and page number. This use of visualization creates a mnemonic representation of a key concept in each article: a submarine in dry dock epitomizes the article titled “Loaded,” which examines the use of submarines in transporting drugs out of Columbia. A second table of contents represents the contents of the first half of the magazine, using visualization in a very different manner to facilitate conceptualization of content through categorization (fig. 13). The left column of the page supplies a fairly typical list of contents by title and page number, dividing them into sections or “departments.” The bulk of the magazine is divided into three sections: “Start” (which is vague regarding its content); “Test” (which, as the title suggests, contains analysis and assessment of some sort); and “Play” (a section on toys and games of various kinds). These departments are more or less consistent from issue to issue, and the representation of them and their contents is entirely conventional. More interesting is the colour-bar at the top of this table of contents, which extends the columns of the table to the right, beyond the page numbers, to provide a grid that identifies a wide range of topics -- diagnostics; animals; the senses; business; transportation, etc. -- and marks which are treated in each article. This representation of contents borrows some of the locative function of the index, pointing the reader to articles on a particular theme. It uses visualization to provide a graphic conceptualization of the intellectual content of the entire first half or so of the magazine, marking each thematic unit with a colour cube: this gives a quantitative view of the articles that treat each theme and where they concentrate within the structure of the magazine. One can quickly see, for example, that “celebrities” concern a relatively small portion and that the topic of “problem-solving” occurs exclusively in the first half of these contents. In this respect, this table of contents also serves an analytical function.

Figure 14

Click For Larger Image

The representation of contentsin the online version of Wired 19.04 (Apr 2011) CLOSE or ESC

In print, the table of contents is a highly refined element of architecture. It remains to be seen how the affordances of the electronic medium will be exploited to extend further the functionality of representations of contents. In the case of the 19.04 issue of Wired, the electronic expression of the same content in fact loses some of the functionality present in the print edition. First, it should be noted that the Wired website is in many respects a very different publication: although it publishes each issue as a contained object, its homepage represents content in a more aggregated manner, rolling new content out on a continuous basis, while at the same time listing content from its current issue. The emphasis in its representation of contents, however, is the menu that runs through the centre of the screen and provides access to the full contents of past and present issues of the site by category and subcategory. The main concern here is the representation of the single issue and how it compares to its counterpart in print. The Web version lacks the graphical enhancements, and thus the added features of thematic summary, conceptualization, and analysis. The only graphical representation is the title page image, which serves only as a link to the corresponding article in the Web version. The rest of the contents are presented as a simple list that much more resembles the simple table of contents of the twentieth-century book than it does the innovative representation of the print edition of the same issue (fig. 14). One can, of course, use the global menu to navigate the whole site by category and sub-category, but these do not give access to content by theme as the print issue does; and while one can do a global keyword search of the whole site and, perhaps, locate articles related to diagnostics, animals, or the senses, this search will return undigested results from the aggregate, not the particular issue. Above all, there is no corresponding view of the contents of a particular issue that enables the same quantified, visual analysis of the conceptual content of either a single issue or the entire contents of the Wired corpus.

A representation of contents, whatever form it takes, is effective to the degree to which it leverages the affordances of its medium to enable the navigational functions that are required or desired of a text of its type. The best new developments in representing contents seek to leverage the affordances of the new medium to enhance and build upon the functionality that has been achieved in the old. Some inherited mechanisms for representing the contents of old forms, such as the monograph, continue to develop along a trajectory established in print. At the same time, new forms of intellectual content will inspire new means for representing contents.

Avrin, Leila. Scribes, Script, and Books: The Book Arts from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Chicago: American Library Association, 1991.

Bacon, Francis. Of the Advancement and Proficience of Learning; Or, the Partitions of Sciences, IX Bookes. Oxford, 1640.

Boece, Hector. [Heir Beginnis the Hystory and Croniklis of Scotland]. Edinburgh, [1540?].

Caxton, William. [Here begynneth the boke intituled Eracles, and also of Godefrey of Boloyne the whiche speketh of the conquest of the holy londe of Iherusalem]. Westminster, 1481.

Darnton, Robert. "Philosophers Trim the Tree of Knowledge: The Epistemological Strategy of the Encyclopédie." In The Great Cat Massacre: And Other Episodes in French Cultural History, 191-213. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Genette, Gerard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Grafton, Anthony, and Megan Williams. Christianity and the Transformation of the Book: Origen, Eusebius, and the Library of Caesarea. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2006.

Hamesse, Jacqueline. "The Scholastic Model of Reading." In A History of Reading in the West, edited by Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane, 103-19. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1999.

Hooker, Richard. Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. London, 1611.

Martin, Henri-Jean, and Jean Vezin. Mise en Page et Mise en Texte du Livre Manuscrit. Paris: Editions du Cercle de la Librairie-Promodis, 1990.

McMurtrie, Douglas C. The Book: The Story of Printing and Bookmaking. London: Oxford University Press, 1943.

Morgan, Nigel J., and Rodney M. Thomson, eds. The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. Vol. 2, 1100-1400. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Nelson, Brent, et. al. "A Short History and Demonstration of the Dynamic Table of Contexts." Scholarly and Research Communication 13.4 (2012). http://src-online.ca/index.php/src/article/view/55.

Parkes, Malcolm Beckwith. "Layout and Presentation of the Text." In vol. 2 of The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, edited by Nigel Morgan and Rodney M. Thomson, 55-74. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Parkes, Malcolm Beckwith. "The Influence of the Concepts of Ordinatio and Compilatio on the Development of the Book." In Medieval Learning and Literature: Essays Presented to Richard William Hunt, edited by J. J. G. Alexander and M. T. Gibson, 115-41. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Pliny the elder. Natural History. Vol. 1. Edited by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938.

Robinson, Pamela. "The Format of Books - Books, Booklets and Rolls." In The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume 2, 1100-1400, edited by Nigel Morgan and Rodney M. Thomson, 41-54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Rock, Daniel. The Church of Our Fathers as Seen in St. Osmund's Rite for the Cathedral of Salisbury. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. London: John Murray, 1905.

Roston, Murray. The Soul of Wit: A Study of John Donne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Rouse, Mary A., and Richard H. Rouse. "La naissance des index." In Histoire de l'édition française, vol. 1, edited by Henri-Jean Martin and Roger Chartier, 77-85. Paris: Promodis, 1990.

"P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange." TEI: Text Encoding Initiative. http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/index.html

Wiseman, D. J. "Books in the Ancient Near East and in the Old Testament." In The Cambridge History of the Bible. Volume 1, From the Beginnings to Jerome, edited by P. R. Ackroyd and C. F. Evans, 30-48. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.