ArchBook: Architectures of the Book

Published 20 January 2012

Corrected and updated 9 March 2022

The variorum commentary notes are those appended to the primary text of a work (be it a poem or collection of poems, a play, or a prose work) in a variorum edition. The term variorum alludes to the Latin phrase editio cum notis variorum, that is, “an edition with the notes of the various [editors and commentators],” a phrase indicating the chief purpose of a variorum edition: namely, to collect and present what has been written by various commentators, critics, and editors on a particular text. Variorum editions are necessary only for works that have attracted detailed comment, explanation, and interpretation over a long period of time and that remain of interest. The sheer volume of writing about these denies a reader the opportunity to access it all without expending enormous resources of time and effort. However, a reader who values the primary text will want to engage with it in the most informed way, that is, in the way that a scholar would. The commentary of a variorum edition permits a reader to do so by assembling all significant comment and associating it with the particular words, lines, or passages to which it applies. When the comments have reference to the work as a whole, they are organized by topic in appendices. With access to this accumulation, the reader can then proceed to determine if there is an opportunity to add anything original. Variorum editions are also of use to editors of less exhaustive editions in providing, in useable form, many of the texts needed.

Because compilation of variorum commentary is a great labour, it has traditionally been preserved in the form of the book, which has proved durable over hundreds of years. More recently, though, the processes of compilation of such commentary have been digital. There is nothing in the nature of variorum commentary to forbid its preservation and dissemination in digital form, provided that its encoding is sufficiently rich to capture the wide range of special characters Character any single meaningful mark that occurs in graphological communication; any single letter, punctuation mark, or special mark such as an asterisk, ampersand or question mark is a character, regardless of whether it is written by hand, printed, or manifested on a computer screen. See: Glyph CLOSE or ESC and formats that necessarily accumulate as it draws together writing from many different times and places. Extensible Mark-up Language (XML) made to conform to the Textual Encoding Initiative (TEI) has proved equal to the task. Now that humanities scholars work as often in digital media as in print, the value of variorum commentary offered digitally will be as great as it has been in print. What remains to be determined is whether the digital medium will prove to be as sustainable over time as the book has proved to be.

The earliest scholar credited with the creation of variorum commentaries is Didymos Khalkenteros (who flourished in the latter half of the first century BCE in Alexandria). His nickname Khalkenteros means “he of the brazen guts,” apparently referring to his prodigious capacity for reading and writing books, his output estimated at 3500 books. He edited works by, among others, Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, Aiskhylos, Sophokles, Euripides, Aristophanes, and Menander.1 His few extant works are written on papyrus that survives in a fragmentary state.

In the Middle Ages, it is scripture and canon law that attract such voluminous commentary as to challenge scribes to achieve layout Layout a plan for the appearance of a piece of printed work. See: PDF Page CLOSE or ESC that can present readers with the excerpt from the text on the same page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC as the accumulated commentary on it;2 such a challenge continues to confront these scribes’ successors whether they publish in book or digital forms. Scribes have to write a signe-de-renvoi at the bottom of a page to link an incomplete commentary note or gloss to its continuation on the next page.3 The Glossa Ordinaria (“the ordinary interpretation/explanation” of scripture) shows the scribe using all four margins Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC surrounding the passage for the commentary. The Catholic Encyclopedia entry “Glosses, Glossaries, Glossarists” describes the growth of the commentary notes accompanying the body of canon law from brief interlinear Interlinear written or printed between the normal lines of text. CLOSE or ESC annotations that come to overflow into the margins. As the number of commentators increases, these notes assume the variorum shape of small essays providing the views of each, with their successors subtending their own remarks, each “placing a significant abbreviation after his gloss, thus: Hug. or H. (Huguccio); Jo. Fa. or F. (Joannes Faventinus).”4

The scribal method of displaying glosses on scripture was subsequently adapted by Early Modern printers to their presentation of the texts of classical writers. Take, for example, a 1519 edition of Horace’s works: Opera Q. horatti Flacci Poetae amoenissimi: cum quatuor comme [n] tariis. Acronis. Porphyrionis. Anto. Mancinelli. Iodoci Badii Ascensii accurate repositis. Cu [m] q[ue] adnotationibus Matthaei Bonfini (“The works of the most delightful poet Q. Horatius Flaccus with the four commentaries of Acro, Porphyrio, Anto. Manciello, Jodocus Badius Ascensius, carefully edited. With the annotations of Mattheus Bonfino”).5 All of Horace’s text that appears on the edition’s first page is the title of his poem and the first two lines. The rest of the page is occupied by commentary, which entirely frames this text. The printer Badius Ascenius, who also functions as editor, collects in his margins all the available commentary on the Horatian text, beginning with that of the “Pseudo-Acro, a grammarian thought to be of the 4th century A.D., and Pomponious Porphyrio, a second- or third-century grammarian.”6 On the variorum principle, and as in the commentary on canon law, each commentator’s notes are distinguished by an abbreviation of his name: for example “ACR.” for Acro.

There have subsequently been variorum editions of many vernacular writers: some of single authors (such as Ruggiers’ The Variorum Chaucer), some of a genre in the oeuvre of an author (Stringer et al.’s Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne), some consisting only of commentary without a text (Hughes et al.’s A Variorum Commentary on the Poems of John Milton), some dealing only with a single work of an author (Peckham’s The Origin of Species: A Variorum Text or Steffan and Pratt’s Byron’s “Don Juan”: A Variorum Edition).7 A variorum in Chinese of the collected writings of Mao Zedong to 1949 is Mao Tse-tung chi, ed. by Minoru Takeuchi, 10 vols. (1970-72), completed by a set of supplements, Mao Tse-tung chi pu chüan (1983-85).8

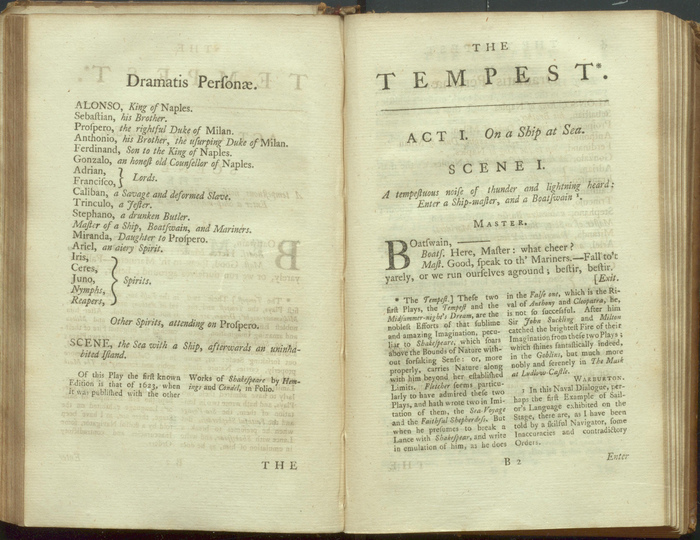

Figure 1

Click For Larger Image

The Plays of William Shakespeare, 1765.Shakespeare, William. The plays of William Shakespeare in eight volumes, with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators; to which are added notes by Sam Johnson. Vol. 1, ed. Samuel Johnson. London: Printed for J. and R. Tonson, etc., 1765. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

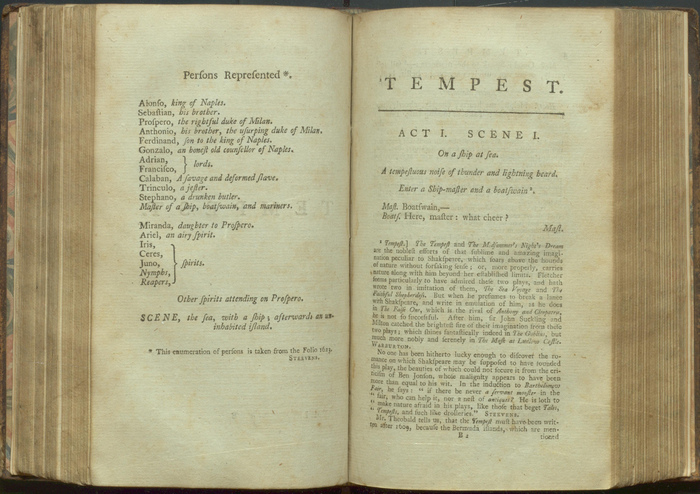

Figure 2

Click For Larger Image

The Plays of William Shakespeare, 1785. Shakespeare, William. The plays of William Shakespeare: in ten volumes: with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators. Vol. 1, ed. Samuel Johnson, George Steevens, and Isaac Reed. London: Printed for C. Bathurst, J. Rivington and Sons ... [and 28 others], 1785. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

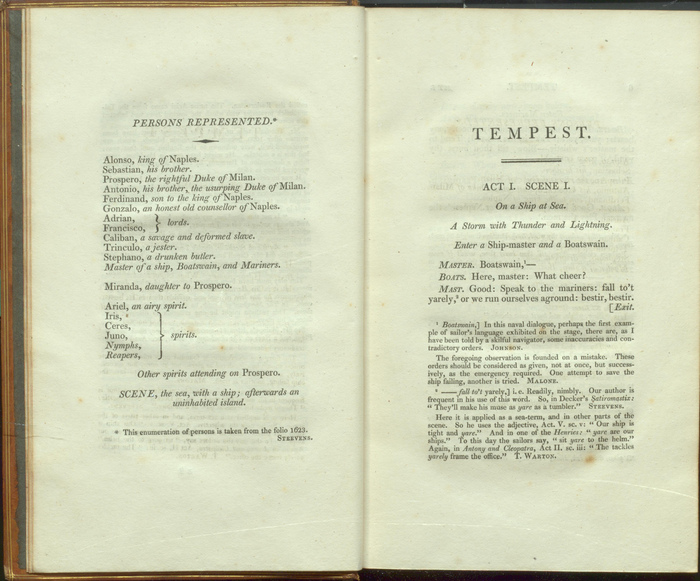

Figure 3

Click For Larger Image

The Plays of William Shakespeare, 1813. Shakespeare, William. The plays of William Shakespeare: in twenty-one volumes, with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators. Vol. 4, ed. Isaac Reed, Samuel Johnson, George Steevens, et al. London: Printed for J. Nichols and Son, 1813. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

However, it is Shakespeare’s plays, and later his plays and poems, that have been most persistently edited in the variorum format. The 1773 edition of the plays is generally thought to be the first variorum edition of Shakespeare, inaugurating an editorial tradition sustained until 1821. The 1773 edition is entitled The plays of William Shakespeare. In ten volumes. With the corrections and illustrations of various commentators; to which are added notes by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens.9 Its phrase “with the corrections and illustrations of various commentators” alludes to the Latin phrase editio cum notis variorum from which the term “variorum edition” derives. (Johnson’s use of the same language in the titles of his 1765 editions indicates an ambition to produce a variorum edition that he did not quite achieve).10 Such an edition offers its readers all that has been written about these Shakespeare texts for as long as they have been the object of study. A second variorum Shakespeare, again by Johnson and Steevens, appeared in 1778, expanded in 1780 by Edmond Malone’s two-volume Supplement, including Pericles and a number of the apocryphal plays.11 Expansion is the persistent pattern, as the commentary notes grow in the 1785 edition (by Johnson, Steevens, and Isaac Reed), the 1793 (by Steevens and Reed), the 1803, and 1813 (by Reed alone), and finally the 1821 (by James Boswell, completing the work he had shared with the late Malone), the last in twenty-one volumes.12

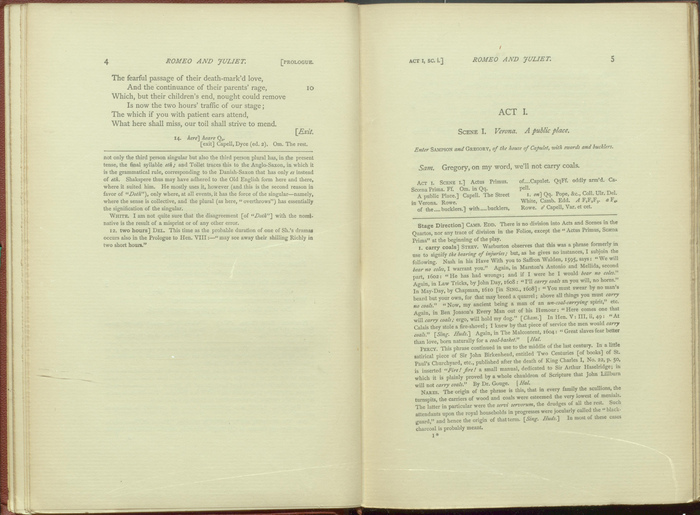

Figure 4

Click For Larger Image

Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare, 1871 Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. ed. H. H. Furness. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1871. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 5

Click For Larger Image

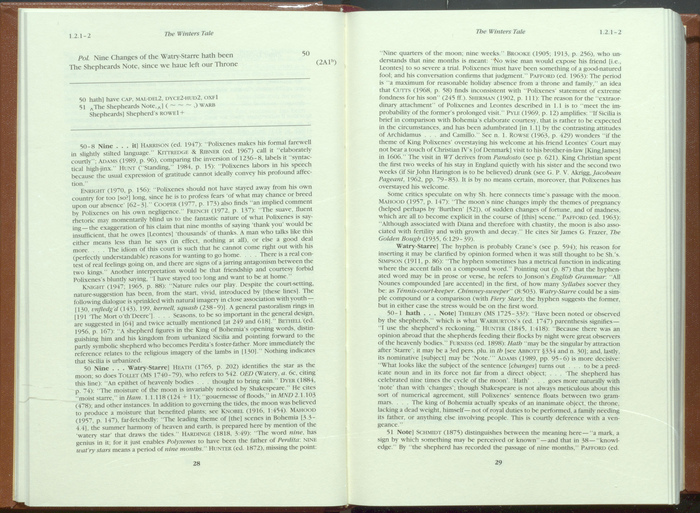

The Winter’s Tale, William Shakespeare, 2005. Shakespeare, William. The Winter’s Tale. ed. Robert Kean Turner, Virginia Westling Haas, Robert A. Jones, Andrew J. Sabol, and Patricia Elizabeth Tatspaugh. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2005. CLOSE or ESC

The New Variorum Shakespeare (NVS) was founded in 1871 by the Philadelphia lawyer Horace Howard Furness (1833-1912) and today continues to be published by the Modern Language Association (MLA). Furness called it new to distinguish it from the Boswell-Malone edition of 1821. The NVS had its genesis in the meetings of the Shakspere [sic] Society of Philadelphia, a gentlemen’s club first devoted to reading a Shakespeare play in an evening, but developing into a group bent upon establishing a text of Shakespeare by reference to the complete reception history of a work. Without a variorum edition more recent than the Boswell-Malone of 1821 and with subsequent writing about Shakespeare dispersed among hundreds of individual publications, Furness experienced only frustration in his attempts to collect and arrange commentary since 1821 in thick scrapbooks. Hence his resolution again to publish Shakespeare in variorum.13 Furness began with Romeo and Juliet.14 Altogether, he and his son, Howard Horace Furness, Jr., who started work in 1901 and succeeded his father in 1912, brought out nineteen plays, including a two-volume Hamlet, before Furness, Jr.’s death in 1930.15 In 1933 the series became an MLA project, and from 1936 to 1955, professional scholars produced seven more volumes, including Hyder E. Rollins’s great two-volume edition of The Sonnets.16 Lack of funding led to a hiatus, but the series resumed publication in the 1970s. In 1977 the MLA published Richard Knowles’s As You Like It, in 1980 Mark Eccles’s Measure for Measure, Marvin Spevack’s Antony and Cleopatra in 1990, and Robert Turner and Virginia Haas’s The Winter’s Tale in 2005.17 Scholars in North America and Europe are actively at work on many more volumes, which will be published, like the 2005 Winter’s Tale, both as books and electronic editions (i.e., PDFs with cross-references as hypertext Hypertext any system which allows the connection and navigation of computer documents through links. CLOSE or ESC links).

Perhaps it is the long history of editing Shakespeare in the variorum format that leads noted textual theorist David Greetham to take the NVS as the example of editing in this format and to regard its arrangement of text, textual notes, and commentary notes as standard. Here is Greetham’s description of a page in NVS:

The text-page of the Variorum is divided into three sections. The upper section presents [a slightly edited] old-spelling reprint of the copy-text Copy Text manuscript or typescript that is to be set in type and printed. CLOSE or ESC. . . . The middle section records the textual emendations to the copy-text made by previous editors . . . , and the lower section lists the commentary . . . by editors and critics.18This core is followed by a number of appendices providing, in the form of excerpts, paraphrases, and summaries, all discussion of the play’s textual problems, date, sources, criticism and history of production on stage, followed by a bibliography of all items cited. These appendices digest a great deal of material in a severely limited compass and lavishly employ cross-references (especially to the bibliography).

Today’s NVS editions therefore represent a transformation of both the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Shakespeare variorums, including Furness’s. In spite of the expansion of commentary on Shakespeare in these earlier centuries, variorum editors were still able to assemble verbatim quotations of their predecessors’ views, either in commentary notes appended to the text of the plays or in appendices. However, with the explosion of writing about Shakespeare since the end of the Second World War, the NVS can no longer accommodate full quotation of the commentators but must resort to excerption, paraphrase, and summary as modes of representation. Therefore when there appears in the NVS series an edition of a play like The Winter’s Tale, a play also edited by Furness, the editors of the new edition do not present their work as supplanting Furness’s, but only as supplementing it, because Furness had the space to include far more of the words of the commentators included in both the 1898 and the 2005 editions.19

Figure 6

Click For Larger Image

The Poetry of John Donne, 1995.Donne, John. The variorum edition of the poetry of John Donne. ed. Gary A. Stringer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995. CLOSE or ESC

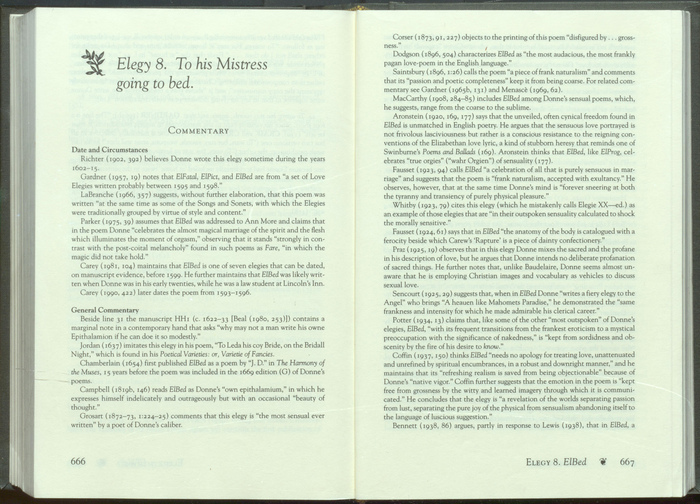

Although Greetham takes the NVS as representative of the variorum edition as a scholarly genre, in practice variorum editing is highly variable. While the variorum edition of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer uses the same format for the core of its volumes found in the NVS, it varies from NVS in locating in its introductions what the NVS includes in its appendices.20 Other variorum editions vary more widely from the NVS. The Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne first prints its text of a poem in its entirety, then places on subsequent pages the whole of the textual apparatus regarding that poem, and, only after having presented the texts and apparatuses for each of the poems, does it collect the whole of the commentary on all the poems in a volume at the end of that volume.21 Steffan and Pratt's edition of Byron's Don Juan provides the text of its poem canto by canto in its second and third volumes, offering the textual notes to each canto after the canto itself, but reserves the commentary on the poem for its fourth volume.22 The Milton variorum is, as identified in its title, A Variorum Commentary on the Poems of John Milton and therefore includes no text or textual notes.23 In contrast, Peckham's work on Darwin's Origin is, according to the characterization of it provided in its own introduction, “a variorum text,” not “a variorum edition,” insofar as it provides in readable form only the text of the 1859 edition, together with all the changes to it introduced by Darwin himself in the subsequent five editions he prepared.24

Electronic transformation

There are available several examples of variorum commentary in electronic form. They provide an opportunity to assess the extent to which the electronic medium has afforded editors opportunities to address the challenges that have dogged variorum editors over the millennium and more in which they have been confined to the codex—and especially the challenge of providing the reader with simultaneous access to text and relevant commentary. hamletworks.org is an open-source site on which the current editors of the in-progress NVS Hamlet—Editor Eric Rasmussen and Assistant Editors Hardin Aasand and Frank Nicholas Clary, together with former Editor the late Bernice W. Kliman—have put up the notes they have compiled in the preparation of their edition, as well as other essays and resources independent of that edition. They address the challenge of displaying text together with commentary through an incremental mode of organization. The reader can access commentary notes on a screen containing a single line from the play subtended by the notes relevant to that line by a number of commentators from across the history of reception of the play, each note associated with its author and date of publication, some containing full bibliographical information. As the reader proceeds through the commentary, the line of the text quickly disappears, but it can be quickly, if not instantly, recovered by scrolling backward through the commentary the reader has already surveyed. Ironically, this form of display uses the electronic medium that has succeeded the codex to return the reader to the medium that preceded the codex—the scroll Scroll a textual form made of a single rolled substrate. Read by unrolling horizontally See: Roll Pagina CLOSE or ESC, which had its own commendable features.

The reader of the University of Oxford’s Thomas Gray Archive (thomasgray.org—a site discussed in detail by Lavagnino), has no opportunity to view the primary text and annotation at precisely the same time, but this apparent disadvantage is offset by the electronic medium's hypertext links.25 Navigating this site, the reader is taken from a screen containing the relevant primary text to one containing only the commentary notes on it. These notes, quoted in full, are each subtended by the full bibliographical information for their sources. The reader can instantly switch back and forth between text and commentary, thereby bringing the one into relation with the other.

The NVS Winter’s Tale and Comedy of Errors, the most recent publications in that series, appeared both in book form and on a CD in a pocket inside the back cover. The electronic version of the edition on the CD consists of a PDF of the book, with cross-references, including all those to the bibliography and the bibliographical plan of the work, as hypertext links. This volume has also been encoded in TEI-conformant XML by Julia Flanders. Such encoding offers still other opportunities to manage the voluminousness of variorum commentary, a problem that has dogged us since scribes copied the Glossa Ordinaria. For example, in one prototype interface mode devised by Alan Galey, the text of the play alone appears. In this mode, each line can be clicked in order to open in a box beside the text the commentary notes associated with that particular line. If the commentary note is extensive (as is often the case in the NVS), the box in which it appears is scrollable so that the reader never loses sight of the line of text in reading the commentary on it. In a second interface mode, the reader can choose to fill the screen with commentary notes alone, together with the lines of text to which they refer. For illustrations of this prototype interface, see Werstine.26

Byron (George Gordon, Lord Byron). Byron's "Don Juan": A Variorum Edition. Edited by Truman Guy Steffan and William W. Pratt. 4 vols. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1957.

The Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. "Glosses, Glossaries, Glossarists." Accessed May 18, 2012. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06588a.htm.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Variorum Chaucher. Edited by Paul Ruggiers. Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 1979.

Darwin, Charles. The Origin of Species: A Variorum Text. Edited by Morse Peckham. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1959.

Donne, John. Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne. Edited by Gary Stringer et al. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Gibson, James M. The Philadelphia Shakespeare Story: Horace Howard Furness and the Variorum Shakespeare. New York: AMS Press, 1990.

Grafton, Anthony. The Footnote: A Curious History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Greetham, David. Textual Scholarship: An Introduction. New York: Garland, 1994.

Harding, Philip. Didymos on Demosthenes: Introduction, Text, Translation, and Commentary. Oxford: Clarendon, 2006.

Lavagnino, John. "Two Varieties of Digital Commentary." In Textual Performances: The Modern Reproduction of Shakespeare's Drama. Edited by Lukas Erne and Margaret Jane Kidnie, 194-209. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Mao Zedong. Mao Tse-tung chi. Edited by Minoru Takeuchi. 10 vols. Supplements: Mao Tse-tung chi pu chuan. 1970-1972 and 1983-1985.

Milton, John. A Variorum Commentary on the Poems of John Milton. Edited by Merritt Y. Hughes et al. 6 vols. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970-75.

Parkes, Malcolm Beckwith. "Layout and Presentation of the Text." In vol. 2 of The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, edited by Nigel Morgan and Rodney M. Thomson, 55-74. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by Samuel Johnson. 8 vols. London, 1765.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. 10 vols. London, 1773.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. 10 Vols. With Supplement. Edited by Edmond Malone. 2 Vols. London, 1778 and 1780.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by Samuel Johnson, George Steevens and Isaac Reed. 10 vols. 1785.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by George Steevens and Isaac Reed. 15 vols. 1793.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by Isaac Reed. 21 vols. 1803.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays of William Shakespeare. Edited by Isaac Reed. 21 vols. 1813.

Shakespeare, William. The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare. Edited by James Boswell and Edmond Malone. 21 vols. London: RC & J Rivington (etc.), 1821.

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by H. H. Furness. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1871.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by H. H. Furness. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1877.

Shakespeare, William. The Winter's Tale. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by H. H. Furness. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1898.

Shakespeare, William. The Sonnets. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by Hyder E. Rollins. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1944.

Shakespeare, William. As You Like It. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by Richard Knowles. New York: MLA, 1977.

Shakespeare, William. Measure for Measure. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by Mark Eccles. New York: MLA, 1980.

Shakespeare, William. Antony and Cleopatra. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by Marvin Spevack, et al. New York: MLA, 1990.

Shakespeare, William. The Winter's Tale. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Edited by Virginia Westling Haas and Robert Kean Turner. New York: MLA, 2005.

Thomas Gray Archive. http://www.thomasgray.org/.

Tribble, Evelyn B. Margins and Marginality. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993.

Werstine, Paul. "Past is Prologue: Electronic New Variorum Shakespeares." Shakespeare 4, no. 3 (2008): 224-36.

Berger, Thomas L. "Press Variants in Substantive Shakespearian Dramatic Quartos." The Library. 6th ser. 10 (1988): 231-41.

Best, Michael. "Shakespeare and the Electronic Text." A Concise Companion to Shakespeare and the Text, edited by Andrew Murphy, 145-61. Oxford: Blackwell, 2007.

Branmuller, A. R. "Shakespeares Various." In In Arden: Editing Shakespeare, edited by Ann Thompson and Gordon McMullan, 3-16. London: Arden Shakespeare - Thompson Learning, 2003.

Clary, Frank Nicholas. "Charles Gildon's Editorial Apparatus and Nicholas Rowe's Hamlet." Hamlet Studies 25 (2003): 156-74.

Crane, Gregory. "In a Digital World, No Book is an Island: Designing Electronic Primary Sources and Reference Works for the Humanities." In Creation, Use, and Deployment of Digital Information, edited by Herre Van Oostendorp, Leen Breure, and Andrew Dillon, 11-26. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005.

Crane, Gregory, et al. "Drudgery and Deep Thought." Communications of the ACM 44, no. 5 (2001): 34-40.

Gondris, Joanna. "'All This Farrago': The Eighteenth-Century Shakespeare Variorum Page as a Critical Structure." In Reading Readings: Essays on Shakespeare Editing in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Joanna Gondris, 123-39. Madison, WI: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1998.

Hunt, Maurice. "New Variorum Shakespeares in the Twenty-First Century." Yearbook of English Studies 29 (1999): 57-68.

Kliman, Bernice W. "Print and Electronic Editions Inspired by the New Variorum Hamlet Project." Shakespeare Survey 59 (2006): 157-67.

Knowles, Richard. "Variorum Commentary." TEXT 6 (1994): 35-47.

Knowles, Richard. "What's New In the New Variorum?" Shakespearean International Yearbook 2 (2002): 143-9.

Knowles, Richard. Shakespeare Variorum Handbook: A Manual of Editorial Practice. New York: MLA, 2003.

Murphy, Andrew. Shakespeare in Print: A History and Chronology of Shakespeare Publishing. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Smith, David Nichol. Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928.