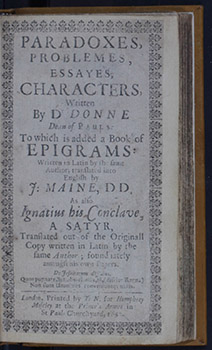

PARADOXES,

PROBLEMES,

ESSAYES,

CHARACTERS,

Written

By Dr DONNE

Dean of PAULS:

To which is added a Book of

EPIGRAMS:

Written in Latin by the same

Author; translated into

English by

I: MAINE, D. D.

As also

Ignatius his Conclave,

A SATYR,

Translated out of the Originall

Copy written in Latin by the

same Author; found

lately amongst his own Papers. Quos pugnare, Scholis, clamāt, hi, (discite Regna) Non sunt Unanimes, conveniuntq;qie nimis.

Printed by T: N: for Humphrey

Moseley at the Prince's Armes in

St Pauls Churchyard, 1652

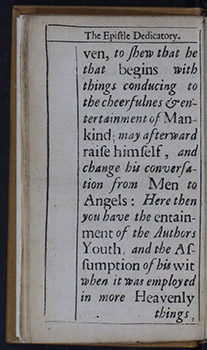

The Table.

PARADOXES.

I.

The Table.

PARADOXES.

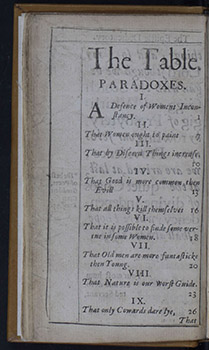

I. A Defence of Womens Incon-

stancy. 1 II.

That Women ought to paint 7 III.

That by Discord Things increase. 10 IV.

That Good is more common then

Evill 13 V.

That all things kill themselves 16 VI.

That it is possible to finde some ver-

tue in some Women. 18 VII.

That Old men are more fantasticke

then Young. 20 VIII.

That Nature is our worst Guide. 23 IX.

That only Cowards dare lye, 26 That

The Table

X.

The Table

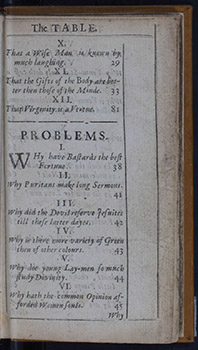

X. That a Wise Man is known by

much laughing. 29 XI.

That the Gifts of the Body are bet-

ter then those of the Minde. 33 XII.

That Virginity is a Vertue. 81 PROBLEMS. I.

WHyWhy have Bastards the best

Fortune. 38 II.

Why Puritans make long Sermons. 41 III.

Why did the Devil reserve Iesuites

till these latter dayes. 42 IV.

Why is there more variety of Green

then of other colours. 43 V.

Why doe young Lay-men so much

study Divinity. 44 VI.

Why hath the common Opinion af-

forded Women souls. 45 Why

The Table

VII.

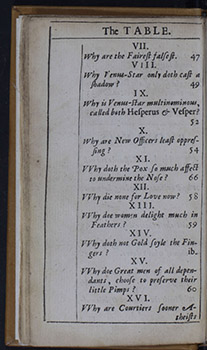

The Table

VII. Why are the Fairest falsest. 47 VIII.

Why Venus-Star only doth cast a

shadow? 49 IX.

Why is Venus-star multinominous,

called both Hesperus & Vesper? 52 X.

Why are New Officers least oppres-

sing? 54 XI.

VVhyWhy doth the Pox so much affect

to undermine the Nose? 66 XII.

VVhyWhy die none for Love now? 58 XIII.

VVhyWhy doe women delight much in

Feathers? 59 XIV.

VVhyWhy doth not Gold soyle the Fin-

gers? ib. XV.

VVhyWhy doe Great men of all depen-

dants, choose to preserve their

little Pimps? 60 XVI.

VVhyWhy are Courtiers sooner A-

theists

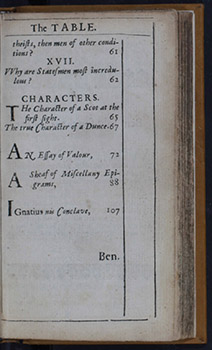

The Table

theists, then men of other condi-

The Table

theists, then men of other condi-tions? 61 XVII.

VVhyWhy are Statesmen most incredu-

lous? 62 CHARACTERS. THeThe Character of a Scot at the

first sight. 65 The true Character of a Dunce. 67 ANAn Essay of Valour, 72 A Sheaf of Miscellany Epi-

grams, 88 IGnatiusIgnatius nis Conclave, 107

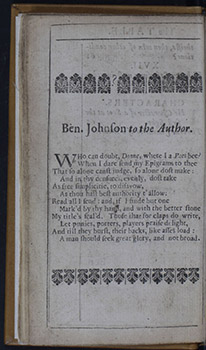

Ben. Johnson to the Author.

WHoWho can doubt, Donne, where I a Poet bee?

When I dare send my Epigrams to thee

That so alone canst judge, so alone dost make:

And in thy censures, evenly, dost take

As free simplicitie, to disavow,

As thou hast best authority t'allow:

Read all I send: and, if I finde but one

Mark'd by thy hand, and with the better stone

My title's seal'd. Those that for claps do write,

Let punies, porters, players praise delight,

And till they burst, their backs, like asses load:

A man should seek great glory, and not broad.

Ben. Johnson to the Author.

WHoWho can doubt, Donne, where I a Poet bee?

When I dare send my Epigrams to thee

That so alone canst judge, so alone dost make:

And in thy censures, evenly, dost take

As free simplicitie, to disavow,

As thou hast best authority t'allow:

Read all I send: and, if I finde but one

Mark'd by thy hand, and with the better stone

My title's seal'd. Those that for claps do write,

Let punies, porters, players praise delight,

And till they burst, their backs, like asses load:

A man should seek great glory, and not broad.

1

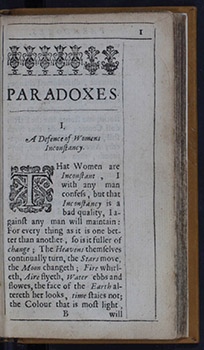

PARADOXES.

I.

1

PARADOXES.

I.

A Defence of Womens

Inconstancy.

THhat Women are

Inconstant, I

with any man

confess, but that

Inconstancy is a

bad quality, I a-

gainst any man will maintain:

For every thing as it is one bet-

ter than another, so is it fuller of

change; The Heavens themselves

continually turn, the Stars move,

the Moon changeth; Fire whirl-

eth, Aire flyeth, Water ebbs and

flowes, the face of the Earth al-

tereth her looks, time staies not;

the Colour that is most light,

2

PARADOXES.

2

PARADOXES.

will take most dyes: so in Men,

they that have the most reason

are the most inalterable in their

designes, and the darkest or most

ignorant, do seldomest change;

therfore Women changing more

than Men, have also more Reason.

They cannot be immutable like

stocks, like stones, like the Earths

dull Center; Gold that lyeth

still, rusteth; Water, corrupt-

eth; Aire that moveth not, poy-

soneth; then why should that

which is the perfection of other

things, be imputed to Women as

greatest imperfection? Because

thereby they deceive Men. Are

not your wits pleased with those

jests, which cozen your expecta-

tion? You can cal it pleasure to be

beguil'd in troubles, and in the

most excellent toy in the world,

you call it Treachery: I would

you had your Mistresses so con-

stant, that they would never

change, no not so much as their

smocks, then should you see what

sluttish vertue, Constancy were.

Inconstancy is a most commenda-

PARADOXES.

3

ble and cleanly quality, and Wo-

PARADOXES.

3

ble and cleanly quality, and Wo-men in this quality are far more

absolute than the Heavens, than

the Stars, Moon, or any thing

beneath it; for long observati-

on hath pickt certainty out of

their mutability. The Learned

are so well acquainted with the

Stars, Signes and Planets, that

they make them but Characters,

to read the meaning of the Hea-

ven in his own forehead. Every

simple fellow can bespeak the

change of the Moon a great while

beforehand: but I would fain

have the learnedst man so skilfull,

as to tell when the simplest Wo-

man meaneth to vary. Learning

affords no rules to know, much

less knowledge to rule the minde

of a Woman: For as Philosophy

teacheth us, that Light things do

always tend upwards, and heavy

things decline downward; Ex-

perience teacheth us otherwise,

that the disposition of a Light

Woman, is to fall down, the na-

ture of women being contrary

to all Art and Nature. Women

4

PARADOXES.

4

PARADOXES.

are like Flies, which feed among

us at our Table, or Fleas sucking

our very blood., who leave not

our most retired places free from

their familiarity, yet for all their

fellowship will they never be ta-

med nor commanded by us. Wo-

men are like the Sun, which is vi-

olently carried one way, yet hath

a proper course contrary: so

though they, by the mastery of

some over-ruling churlish hus-

bands, are forced to his Byas,

yet have they a motion of their

own, which their husbands never

know of: It is the nature of

nice and fastidious mindes to

know things only to be wary of

them: Women by their slye

changeableness, and pleasing dou-

bleness, prevent even the mislike

of those, for they can never be so

well known, but that there is still

more unknown. Every woman

is a Science; for he that plods

upon a woman all his life long,

shall at length finde himself short

of the knowledge of her: they

are born to take down the pride

PARADOXES.

5

of wit, and ambition of wisdom,

PARADOXES.

5

of wit, and ambition of wisdom,

making fools wise in the adventu-

ring to win them, wisemen fools

in conceit of losing their labours;

witty men stark mad, being con-

founded with their uncertainties.

Philosophers write against them

for spight, not desert, that having

attained to some knowledge in all

other things, in them only they

know nothing, but are meerly ig-

norant: Active and Experienced

men rail against them, because

they love in their liveless and de-

crepit age, when all goodness

leaves them. These envious Li-

bellers ballad against them, be-

cause having nothing in themselvs

able to deserve their love, they

maliciously discommend all they

cannot obtain, thinking to make

men believe they know much,

because they are able to dispraise

much, and rage against Inconstan-

cy, when they were never admit-

ted into so much favour as to be

forsaken. In mine opinion such

men are happie that women are

Inconstant, for so may they chance

6

PARADOXES.

to be beloved of some excellent

6

PARADOXES.

to be beloved of some excellent

woman when it comes to their

turn out of their Inconstancy

and mutability, though not out

of their own desert. And what

reason is there to clog any wo-

man with one man, be he never so

singular? Women had rather,

and it is far better and more Ju-

dicial to enjoy all the vertues in

several men, than but some of

them in one, for otherwise they

lose their taste, like divers sorts of

meat minced together in one dish:

and to have all excellencies in

one man (if it were possible) is

Confusion and Diversity. Now

who can deny, but such as are

obstinately bent to undervalue

their worth, are those that have

not soul enough to comprehend

their excellency, women being

the most excellent Creatures, in

that man is able to subject all

things else, and to grow wise in

every thing, but still persists a

fool in woman? The greatest

Scholler, if he once take a wife,

is found so unlearned, that he

PARADOXES.

7

must begin his Horn-book, and

PARADOXES.

7

must begin his Horn-book, and

all is by Inconstancy. To con-

clude therefore; this name of

Inconstancy, which hath so much

been poysoned with slanders,

ought to be changed into variety,

for the which the world is so de-

lightfull, and a woman for that the

most delightfull thing in this

world.

II. That Women ought to Paint.

FOoulness is Lothsome: can that

be so which helps it? who

forbids his beloved to gird in her

waste? to mend by shooing her

uneven lameness? to burnish her

teeth? or to perfume her breath?

yet that the Face be more pre-

cisely regarded, it concerns more:

For as open confessing sinners

are always punished, but the wa-

ry and concealing offenders with-

out witness, do it also without

punishment; so the secret parts

8

PARADOXES.

needs the less respect; but of the

8

PARADOXES.

needs the less respect; but of the

Face, discovered to all Examina-

tions and surveys, there is not too

nice a Jealousie. Nor doth it

only draw the busie Eyes, but it

is subject to the divinest touch of

all, to kissing, the strange and

mystical union of souls. If she

should prostitute her self to a

more unworthy man than thy

self, how earnestly and justly

wouldst thou exclaim? that for

want of this easier and ready

way of repairing, to betray her

body to ruine and deformity (the

tyrannous Ravishers, and sodain

Deflourers of all women) what a

hainous adultery is it? What

thou lovest in her face is colour,

and painting gives that, but thou

hatest it, not because it is, but be-

cause thou knowest it. Fool,

whom ignorance makes happy,

the Stars, the Sun, the Skye

whom thou admirest, alas, have

no colour, but are fair, because

they seem to be coloured: If this

seeming will not satisfie thee in

her, thou hast good assurance of

PARADOXES.

9

her colour, when thou seest her

PARADOXES.

9

her colour, when thou seest her

lay it on. If her face be painted

on a Board or Wall, thou wilt

love it, and the Board, and the

Wall: Canst thou loath it then

when it speaks, smiles, and kisses,

because it is painted? Are we

not more delighted with seeing

Birds, Fruits, and Beasts painted

then we are with Naturals? And

do we not with pleasure behold

the painted shape of Monsters

and Devils, whom true, we durst

not regard? We repair the ruines

of our houses, but first cold tem-

pests warns us of it, and bites us

through it; we mend the wrack

and stains of our apparel, but

first our eyes, and other bodies

are offended; but by this pro-

vidence of Women, this is pre-

vented. If in Kissing or breath-

ing upon her, the painting fall

off, thou art angry, wilt thou be

so, if it stick on? Thou didst love

her, if thou beginnest to hate

her, then 'tis because she is not

painted. If thou wilt say now,

thou didst hate her before, thou

10

PARADOXES.

didst hate her and love her toge-

10

PARADOXES.

didst hate her and love her toge-ther, be constant in something,

and love her who shews her great

love to thee, in taking this pains

to seem lovely to thee. III.

That by Discord things in-

crease.

Nullos esse Deos, inane Cœlum

Affirmat Cœlius, probatqque

quod se

Factum vidit, dum negat hæc,

beatum.

SOo I assevere this the more

boldly, because while I main-

tain it, and feel the Contrary re-

pugnancies and adverse fightings

of the Elements in my Body,

my Body increaseth; and whilst I

differ from common opinions by

this Discord, the number of my

Paradoxes increaseth. All the

rich benefits we can frame to our

selves in Concord, is but an Even

PARADOXES.

11

conservation of things; in which

PARADOXES.

11

conservation of things; in which

Evenness vvwe can expect no

change, no motion; therefore no

increase or augmentation, which

is a member of motion. And if

this unity and peace can give in-

crease to things, how mightily is

discord and war to that purpose,

which are indeed the only ordi-

nary Parents of Peace. Discord

is never so barren that it affords

no fruit; for the fall of one e-

state is at the worst the increaser

of another, because it is as im-

possible to finde a discommodity

without advantage, as to finde

Corruption without Generation:

But it is the Nature and Office of

Concord to preserve onely, which

property when it leaves, it differs

from it self, which is the greatest

discord of all. All Victories and

Emperies gained by war, and

all Judiciall decidings of doubts

in peace, I do claim children of

Discord. And who can deny but

Controversies in Religion are

grown greater by Discord, and

not the Controversie, but Religion

12

PARADOXES.

it self: For in a troubled misery

12

PARADOXES.

it self: For in a troubled misery

men are always more Religious

then in a secure peace. The num-

ber of good men, the only chari-

table nourishers of Concord, we

see is thin, and daily melts and

wains; but of bad discording it

is infinite, and growes hourly.

We are ascertained of all Dispu-

table doubts, only by arguing and

differing in Opinion, and if for-

mal disputation (which is but a

painted, counterfeit, and dissem-

bled discord) can work us this be-

nefit, what shall not a full and

main discord accomplish? True-

ly me thinks I owe a devotion, yea

a sacrifice to discord, for casting

that Ball upon Ida, and for all

that business of Troy, whom

ruin'd I admire more then Baby-

lon, Rome, or Quinzay, removed

Corners, not only fulfilled with

her fame, but with Cities and

Thrones planted by her Fugi-

tives. Lastly, between Cowar-

dice and despair, Valour is gen-

dred; and so the Discord of Ex-

treams begets all vertues, but of

PARADOXES.

13

PARADOXES.

13

the like things there is no issue

without a miracle:

VUxor pessima, pessimus maritus

Miror tam malè convenire.

He wonders that between two so

like, there could be any discord,

yet perchance for all this discord

there was ne're the less increase. IV.

That Good is more common

then Evil.

I Havehave not been so pittifully

tired with any vanity, as with

silly Old Mens exclaiming against

these times, and extolling their

own: Alas! they betray them-

selves, for if the times be changed,

their manners have changed

them. But their senses are to

pleasures, as sick mens tastes are

to Liquors; for indeed no new

thing is done in the world, all

things are what, and as they were,

and Good is as ever it was, more

plenteous, and must of necessity

14

PARADOXES.

14

PARADOXES.

be more common then Evil, because

it hath this for nature and per-

fection to be common. It makes

Love to all Natures, all, all af-

fect it. So that in the worlds

early Infancy, there was a time

when nothing was evil, but if

this world shall suffer dotage in

the extreamest crookedness there-

of, there shall be no time when

nothing shall be good. It dares

appear and spread, and glister in

the world, but evil buries it self

in night and darkness, and is chas-

tised and suppressed when good

is cherished and rewarded. And

as Imbroderers, Lapidaries, and

other Artisans, can by all things

adorn their works; for by ad-

ding better things, the better

they shew in Lush and in emi-

nency; so good doth not only

prostrate her amiableness to all,

but refuses no end, no not of her

utter contrary evil, that she may

be the more common to us. For

evil manners are parents of good

Laws; and in every evil there is

an excellency, which (in common

PARADOXES.

15

speech) we call good. For the

PARADOXES.

15

speech) we call good. For the

fashions of habits, for our mo-

ving in gestures, for phrases in

our speech, we say they were good

as long as they were used, that is

as long as they were common;

and we eat, we walk, only when

it is, or seems good to do so. All

fair, all profitable, all vertuous, is,

good, and these three things I

think imbrace all things, but

their utter contraries; of which

also fair may be rich and vertu-

ous; poor may be vertuous and

fair; vitious may be fair and

rich; so that good hath this good

means to be common, that some

subjects she can possess intirely;

and in subjects poysoned with e-

vil, she can humbly stoop to ac-

company the evil. And of in-

different things many things are

become perfectly good by being

common, as customs by use are

made binding Laws. But I re-

member nothing that is therefore

ill, because it is common, but wo-

men, of whom also; They that

are most common, are the best

16

PARADOXES.

of that Occupation they pro-

16

PARADOXES.

of that Occupation they pro-fess.

V.

That all things kill themselves.

TOo affect, yea to effect their

own death all living things

are importuned, not by Na-

ture only which perfects them,

but by Art and Education, which

perfects her. Plants quickened

and inhabited by the most un-

worthy soul, which therefore nei-

ther will nor work, affect an end,

a perfection, a death; this they

spend their spirits to attain, this

attained, they languish and wi-

ther. And by how much more

they are by mans Industry war-

med, cherished and pampered;

so much the more early they

climb to this perfection, this

death. And if amongst men not

to defend be to kill, what a hai-

PARADOXES.

17

nous self-murther is it, not to de-

PARADOXES.

17

nous self-murther is it, not to de-fend itself. This defence because

Beasts neglect, they kill them-

selves, because they exceed us in

number, strength, and a lawless li-

berty: yea, of Horses and other

beasts, they that inherit most cou-

rage by being bred of gallantest

parents, and by Artificial nursing

are bettered, will run to their

own deaths, neither sollicited by

spurs which they need not, nor by

honour which they apprehend

not. If then the valiant kill him-

self, who can excuse the Coward?

Or how shall man be free from

this, since the first man taught us

this, except we cannot kill our

selves, because he kill'd us all.

Yet least something should repair

this common ruine, we daily kill

our bodies with surfeits, and our

minds with anguishes. Of our

powers, remembring kils our me-

mory: Of affections, Lusting

our lust; Of vertues, Giving kils

liberality. And if these kil them-

selves, they do it in their best and

supream perfection: for after per-

18

PARADOXES.

fection immediately follows ex-

18

PARADOXES.

fection immediately follows ex-cess, which changeth the natures

and the names, and makes them

not the same things. If then the

best things kill themselves soon-

est, (for no affection endures, and

all things labour to this perfecti-

on) all travel to their own death,

yea the frame of the whole world,

if it were possible for God to be

idle, yet because it began, must

die. Then in this idleness imagin-

ed in God, what could kill the

world but it self, since out of it,

nothing is?

VI.

That it is possible to finde some ver-

tue in some Women.

I Aam not of that seard Impu-

dence that I dare defend Wo-

men, or pronounce them good,

yet we see Physitians allow some

vertue in every poyson. Alas!

why should we except Women?

since cerrtainly they are good for

PARADOXES.

19

Physick at least, so as some wine

PARADOXES.

19

Physick at least, so as some wine

is good for a feaver. And though

they be the Occasioners of many

sins, they are also the Punishers

and Revengers of the same sins:

For I have seldom seen one which

consumes his substance and body

upon them, escape diseases, or

beggery; and this is their Justice.

And if suum cuique dare, be

the fulfilling of all Civil Justice, they

are most just; for they deny that

which is theirs to no man.

Tanquam non liceat nulla

puella negat.

And who may doubt of great

wisdome in them, that doth but

observe with how much labour

and cunning our Justicers and o-

ther dispensers of the Laws studie

to imbrace them: and how zea-

lously our Preachers dehort men

from them, only by urging their

subtilties and policies, and wisdom,

which are in them? Or who can

deny them a good measure of

Fortitude, if he consider how va-

liant men they have overthrown,

and being themselvs overthrown,

20

PARADOXES.

how much and how patiently

20

PARADOXES.

how much and how patiently

they bear? And though they be

most intemperate, I care not, for

I undertook to furnish them with

some vertue, not with all. Ne-

cessity, which makes even bad

things good, prevails also for

them, for we must say of them,

as of some sharp pinching Laws;

If men were free from infirmities,

they were needless. These or

none must serve for reasons, and

it is my great happiness that Ex-

amples prove not Rules, for to

confirm this Opinion, the World

yeilds not one Example.

VII.

That Old men are more Fantastick

then Young.

WHho reads this Paradox

but thinks me more fan-

tastick now, than I was yester-

day, when I did not think thus:

And if one day make this sensible

change in men, what will the bur-

then of many years? To be fan-

PARADOXES.

21

tastick

in young men is conceit-

PARADOXES.

21

tastick

in young men is conceit-full distemperature, and a witty

madness; but in old men, whose

senses are withered, it becomes na-

tural, therfore more full and per-

fect. For as when we sleep our fan-

cy is most strong; so it is in age,

which is a slumber of the deep sleep

of death. They tax us of Inconstan-

cy, which in themselves young they

allowed; so that reproving that

which they did approve, their In-

constancy exceedeth ours, because

they have changed once more then

we. Yea, they are more idlely bu-

sied in conceited apparel than we;

for we, when we are melancholy,

wear black; when lusty, green;

when forsaken, tawny; pleasing

our own inward affections, lea-

ving them to others indifferent;

but they prescribe laws, and con-

strain the Noble, the Scholler, the

Merchant, and all Estates to a

certain habit. The old men of our

time have changed with patience

their own bodies, much of their

laws, much of their languages;

yea their Religion, yet they accuse

22

PARADOXES.

us. To be Amorous is proper and

22

PARADOXES.

us. To be Amorous is proper and

natural in a young man, but in an

old man most fantastick. And that

ridling humour of Jealousie,

which seeks and would not finde,

which requires and repents his

knowledg, is in them most com-

mon, yet most fantastike. Yea,

that which falls never in young

men, is in them most fantastike

and naturall, that is, Covetous-

nesse; even at their journeys end

to make great provision. Is any

habit of young men so fantastike,

as in the hottest seasons to be dou-

ble-gowned or hooded like our El-

ders? Or seemes it so ridiculous

to weare long haire, as to weare

none. Truely, as among the Phi-

losophers, the Skeptike, which

doubts all, was more contentious,

then either the Dogmatick which

affirmes, or Academike which de-

nies all; so are these uncertain

Elders, which both cals them fan-

tastick which follow others in-

ventions, and them also which

are led by their own humorous

suggestion, more fantastick then

other.

PARADOXES.

23

VIII.

PARADOXES.

23

VIII.

That Nature is our Worst Guid.

SHhall she be guide to all Crea-

tures, which is her self one?

Or if she also have a guide, shall

any Creature have a better guide

then we? The affections of lust

and anger, yea even to err is na-

tural, shall we follow these? Can

she be a good guide to us, which

hath corrupted not us only but

her self? was not the first Man,

by the desire of knowledge, cor-

rupted even in the whitest inte-

grity of Nature? And did not Na-

ture, (if Nature did any thing)

infuse into him this desire of

knowledge, and so this corrupti-

on in him, into us? If by Nature

we shall understand our essence,

our definition or reason, nobleness,

then this being alike common to

all (the Idiot and the Wizard be-

ing equally reasonable) why should

not all men having equally all one

nature,follow one course? Or if we

shall understand our inclinati-

24

PARADOXES.

ons: alas! how unable a guide

24

PARADOXES.

ons: alas! how unable a guide

is that which follows the tempe-

rature of our slimie bodies? for

we cannot say that we derive our

inclinations, our minds, or souls

from our Parents by any way:

to say that it is all from all, is er-

ror in reason, for then with the

first nothing remains, or is a part

from all, is error in experience,

for then this part equally impar-

ted to many children, would like

Gavel-kind lands, in few genera-

tions become nothing: or to say

it by communication, is error in

Divinity, for to communicate the

ability of communicating whole

essence with any but God, is utter

blasphemy. And if thou hit thy

Fathers nature and inclination, he

also had his Fathers, and so

climbing up, all comes of one

man, and have one nature, all

shall imbrace one course; but that

cannot be, therefore our com-

plexions and whole bodies, we in-

herit from Parents; our inclina-

tions and minds follow that: For

our minde is heavy in our bodies

PARADOXES.

25

afflictions, and rejoyceth in our

PARADOXES.

25

afflictions, and rejoyceth in our

bodies pleasure: how then shall

this nature governe us that is go-

verned by the worst part of us?

Nature though oft chased away,

it will return; 'tis true, but those

good motions and inspirations

which be our guides must be woo-

ed, courted, and welcomed, or else

they abandon us. And that old

Axiome, nihil invita, &c. must not

be said thou shalt, but thou wilt

doe nothing against Nature; so

unwilling he notes us to curbe our

naturall appetites. Wee call our

bastards alwayes our naturall issue

and we define a Foole by nothing

so ordinary, as by the name of na-

turall. And that poore know-

ledg whereby we conceive what

rain is, what wind, what thunder,

we call Metaphysicke, supernatu-

rall; such small things, such no

things do we allow to our pliant

Natures apprehension. Lastly,

by following her we lose the plea-

sant, and lawfull commodities of

this life, for we shall drinke water

and eate rootes, and those not

26

PARADOXES.

sweet and delicate, as now by

26

PARADOXES.

sweet and delicate, as now by

Mans art and industry they are

made: we shall lose all the neces-

sities of societies, lawes, arts, and

sciences, which are all the worke-

manship of Man: yea we shall

lack the last best refuge of misery,

death, because no death is naturall:

for if yee will not dare to call all

death violent (though I see not

why sicknesses be not violences)

yet causes of all deaths proceed

of the defect of that which nature

made perfect, and would preserve;

and therefore all against nature.

IX.

That only Cowards dare die.

EXxtreames are equally remo-

ved from the meane; so that

headlong desperatenesse asmuch

offends true valour, as backward

Cowardice: of which sort I rec-

kon justly all un-inforced deaths.

When will your valiant man die

of necessity? so Cowards suffer

what cannot be avoided: and to

PARADOXES.

27

run into death unimportun'd is to

PARADOXES.

27

run into death unimportun'd is to

run into the first condemned de

sperateness. Will he die when he

is rich and happie? then by living

he may do more good: and in affli-

ctions and miseries, death is the

chosen refuge of Cowards.

Fortiter ille facit qui miser

esse potest.

But it is taught and practised a-

mong our Gallants, that rather

than our reputations suffer any

maim, or we any misery, we shall

offer our breasts to the Cannons

mouth, yea to our swords points:

And this seems a very brave and a

very climbing (which is a Cow-

ardly, earthly, and indeed a very

groveling) spirit. vvwhy do they

chain these slaves to the Gallies,

but that they thrust their deaths,

and would at every loose leap in-

to the Sea? vvwhy do they take

weapons from condemned men,

but to barr them of that ease

which Cowards affect, a speedy

death. Truely this life is a tem-

pest, and a warfare, and he which

dares die, to escape the anguish of

28

PARADOXES.

it, seems to me, but so valiant, as

28

PARADOXES.

it, seems to me, but so valiant, as

he which dares hang himself, least

he be prest to the wars. I have

seen one in that extremity of Me

lancholy, which was then become

madness, to make his own breath

an Instrument to stay his breath,

and labour to choak himself; but

alas! he was mad. And we knew

another that languished under

the oppression of a poor disgrace,

so much, that he took more pains

to die, then would have served

to have nourished life and spirit

enough to have out-liv'd his dis-

grace. vvwhat Fool will call this

Cowardlyness, Valour? or this

Baseness, Humility? And lastly,

of these men which die the Alle-

goricall death of entring into Re-

ligion, how few are found fit for

any shew of valiancy? but one-

ly a soft and supple metal, made

only for Cowardly solitariness.

PARADOXES.

29

X.

PARADOXES.

29

X.

That a Wise Man is known by

much laughing.

RIidi, si sapis, ô puella ride; If

thou beest wise, laugh: for

since the powers of discourse, rea-

son, and laughter, be equally pro-

per unto Man only, why shall not

he be only most wise, which hath

most use of laughing, as well as

he which hath most of reasoning

and discoursing? I always did,

and shall understand that Adage;

Per risum multum possis cogno-

scere stultum,

That by much laughing thou

maist know there is a fool, not,

that the laughers are fools, but

that among them there is some

fool, at whom wise men laugh:

which moved Erasmus to put this

as his first Argument in the

mouth of his Folly, that she made

Beholders laugh: for fools are the

most laughed at, and laugh the

least themselves of any. And

30

PARADOXES.

Nature saw this faculty to be so

30

PARADOXES.

Nature saw this faculty to be so

necessary in man, that she hath

been content that by more causes

we should be importuned to

laugh, than to the exercise of any

other power; for things in them-

selves utterly contrary, beget this

effect; for we laugh both at wit-

ty and absurd things: At both

which sorts I have seen men

laugh so long, and so earnestly,

that at last they have wept that

they could laugh no more. And

therefore the Poet having descri-

bed the quietness of a wise retired

man, saith in one, what we have

said before in many lines; Quid

facit Canius tuus? ridet. We

have received that even the extre-

mity of laughing, yea of weeping

also, hath been accounted wis-

dom: and that Democritus and

Heraclitus, the lovers of these

Extreams, have been called lo-

vers of Wisdom. Now among

our wise men I doubt not but ma-

ny would be found, who would

laugh at Heraclitus weeping, none

which weep at Democritus laugh-

PARADOXES.

31

PARADOXES.

31

ing. At the hearing of Comedies

or other witty reports, I have no-

ted some, which not understan-

ding jests; &c. have yet chosen

this as the best means to seem

wise and understanding, to laugh

when their Companions laugh;

and I have presumed them igno-

rant, whom I have seen unmoved.

A fool if he come into a Princes

Court, and see a gay man leaning

at the wall, so glistring, and so

painted in many colours that he is

hardly discerned from one of the

Pictures in the Arras, hanging his

body like an Iron-bound chest, girt

in and thick rib'd with broad gold

laces, may (and commonly doth)

envy him. But alas! shall a wise

man, which may not only not en-

vy, but not pitty this Monster, do

nothing? Yes, let him laugh. And

if one of these hot cholerick fire-

brands, which nourish them-

selves by quarrelling, and kind-

ling others, spit upon a fool

one sparke of disgrace, he, like a

thatcht house quickly burning,

may be angry; but the wise man,

32

PARADOXES.

as cold as the Salamander, may

32

PARADOXES.

as cold as the Salamander, may

not only not be angry with him,

but not be sorry for him; there-

fore let him laugh: so he shall be

known a Man, because he can

laugh, a wise Man that he knows

at what to laugh, and a valiant

Man that he dares laugh: for he

that laughs is justly reputed more

wise, then at whom it is laughed.

And hence I think proceeds that

which in these later formal times

I have much noted; that now

when our superstitious civilitie

of manners is become a mutuall

tickling flattery of one another,

almost every man affecteth an

humour of jesting, and is content

to be deject, and to deform himself,

yea become fool to no other end

that I can spie, but to give his

wise Companion occasion to laugh;

and to shew themselves in prompt-

ness of laughing is so great in

wise men, that I think all wise men,

if any wise man do read this Pa-

radox, will laugh both at it and

me.

PARADOXES.

33

XI.

PARADOXES.

33

XI.

That the Gifts of the Body

are better then those

of the Minde.

I Ssay again, that the body makes

the minde, not that it crea-

ted it a minde, but forms it a

good or a bad minde; and this

minde may be confounded with

soul without any violence or in-

justice to Reason or Philosophy:

then the soul it seems is enabled

by our Body, not this by it. My

Body licenseth my soul to see the

worlds beauties through mine

eyes: to hear pleasant things

through mine ears; and affords it

apt Organs for the convenience

of all perceivable delight. But

alas! my soul cannot make any

part, that is not of it self dispo-

sed to see or hear, though with-

out doubt she be as able and as

willing to see behinde as before.

Now if my soul would say, that

34

PARADOXES.

she enables any part to taste these

34

PARADOXES.

she enables any part to taste these

pleasures, but is her selfe only

delighted with those rich sweet-

nesses which her inward eyes and

senses apprehend, shee should

dissemble; for I see her often

solaced with beauties, which shee

sees through mine eyes, and with

musicke which through mine

eares she heares. This perfection

then my body hath, that it can

impart to my minde all his plea-

sures; and my mind hath still

many, that she can neither teach

my indisposed part her faculties,

nor to the best espoused parts shew

it beauty of Angels, of Musicke,

of Spheres, whereof she boasts

the contemplation. Are chastity,

temperance, and fortitude gifts of

the minde? I appeale to Physiti-

ans whether the cause of these be

not in the body; health is the gift

of the body, and patience in sick-

nesse the gift of the minde: then

who will say that patience is as

good a happinesse, as health,

when wee must be extremely

PARADOXES.

35

miserable to purchase this happi-

PARADOXES.

35

miserable to purchase this happi-nesse. And for nourishing of ci-

vill societies and mutuall love a-

mongst men, which is our chief

end while we are men; I say, this

beauty, presence, and proportion

of the body, hath a more mascu-

line force in begetting this love,

then the vertues of the minde: for

it strikes us suddenly, and pos-

sesseth us immoderately; when

to know those vertues require

some Judgement in him which

shall discerne, a long time and

conversation between them. And

even at last how much of our

faith and beleefe shal we be driven

to bestow, to assure our selves

that these vertues are not counter-

feited: for it is the same to be,

and seem vertuous, because that

he that hath no vertue can dissem-

ble none, but he which hath a

little, may gild and enamell, yea

and transforme much vice into

vertue: For allow a man to be

discreet and flexible to complaints,

which are great vertuous gifts of

the minde, this discretion will be

36

PARADOXES.

to him the soule and Elixir of all

36

PARADOXES.

to him the soule and Elixir of all

vertues, so that touched with this

even pride shall be made humili-

ty; and Cowardice, honourable

and wise valour. But in things

seen there is not this danger, for

the body which thou lovest and

esteemest faire, is faire: certain-

ly if it be not faire in perfection,

yet it is faire in the same degree

that thy Judgment is good. And

in a faire body, I do seldom sus-

pect a disproportioned minde, and

as seldome hope for a good in a

deformed. When I see a goodly

house, I assure my selfe of a wor-

thy possessour, from a ruinous wea-

ther-beaten building I turn away,

because it seems either stuffed

with varlots as a Prison, or hand-

led by an unworthy and negligent

tenant, that so suffers the wast

therof. And truly the gifts of

Fortune, which are riches, are on-

ly handmaids, yea Pandars of

the bodies pleasure; with their ser-

vice we nourish health, and pre-

serve dainty, and wee buy delights

so that vertue which must be lov-

PARADOXES.

37

ed for it selfe, and respects no

PARADOXES.

37

ed for it selfe, and respects no

further end, is indeed nothing:

And riches, whose end is the good

of the body, cannot be so perfectly

good, as the end whereto it le-

vels.

38

PROBLEMS.

38

PROBLEMS.I.

Why have Bastards best Fortune?

BEecause Fortune her

self is a Whore, but

such are not most

indulgent to their

issue; the old na-

tural reason (but

those meeting in stoln love are

most vehement, and so contribute

more spirit then the easie and

lawfull) might govern me, but

that now I see Mistresses are be-

come domestick and in ordinary,

and they and wives wait but by

turns, and agree as well as they

had lived in the Ark.

The old Moral reason (that Ba-

PROBLEMES.

39

PROBLEMES.

39

stards inherit wickedness from

their Parents, and so are in a bet-

ter way to preferment by having a

stock before-hand, then those

that build all their fortune upon

the poor and weak stock of Origi-

nal sin) might prevail with me,

but that since we are fallen into

such times, as now the World

might spare the Devil, because

she could be bad enough without

him. I see men scorn to be wick-

ed by example, or to be beholding

to others for their damnation. It

seems reasonable, that since Laws

rob them of succession in civil be-

nefits, they should have something

else equivalent. As Nature

(which is Laws pattern) having

denyed Women Constancy to

one, hath provided them with

cunning to allure many; and so

Bastards de jure should have bet-

ter wits and experience. But be-

sides that by experience we see

many fools amongst them,

we should take from them one

of their chiefest helps to prefer-

ment, and we should deny them

40

PROBLEMES.

40

PROBLEMES.

to be fools: and (that which is

only left) that women chuse wor-

thier men then their husbands, is

false de facto: either then it must

be that the Church having remo-

ved them from all place in the

publick Service of God, they have

better means than others to be

wicked, and so fortunate: Or else

because the two greatest powers

in this world, the Devil and Prin-

ces concur to their greatness: the

one giving bastardy, the other

legitimation: As Nature frames

and conserves great bodies of con-

traries. Or the cause is, because

they abound most at Court, which

is the forge where fortunes are

made, or at least the shop where

they be sold.

PROBLEMES.

41

II.

PROBLEMES.

41

II.

Why Puritans make long

Sermons

ITt needs not for perspicuousness,

for God knows they are plain

enough: nor do all of them use

Sem-brief-Accents, for some of

them have crotchets enough. It

may be they intend not to rise like

glorious Tapers and Torches, but

like Thin-wretched-sick-watching-

Candles, which languish and are

in a Divine Consumption from the

first minute, yea in their snuff, and

stink, when others are in their

more profitable glory. I have

thought sometimes, that out of

conscience, they allow long measure

to course ware. And sometimes,

that usurping in that place a li-

berty to speak freely of Kings,

they would reigne as long as they

could. But now I think they do

it out of a zealous imagination,

that, It is their duty to Preach

on till their Auditory wake.

42

PROBLEMES.

III.

42

PROBLEMES.

III.

Why did the Divel reserve Jesuites

till these latter dayes.

DIid he know that our Age

would deny the Devils pos-

sessing, and therefore provided by

these to possesse men and king-

domes? Or to end the disputation

of Schoolmen, why the Divel could

not make lice in Egypt; and whe-

ther those things hee presented

there, might be true; hath he sent

us a true and reall plague, worse

than those ten? Or in ostentati-

on of the greatness of his King-

dome, which even division cannot

shake, doth he send us these which

disagree with all the rest? Or

knowing that our times should

discover the Indies, and abolish

their Idolatry, doth he send these

to give them another for it? Or

peradventure they have been in

the Roman Church these thousand

yeeres, though we have called

them by other names.

PROBLEMES.

43

IV.

PROBLEMES.

43

IV.

Why is there more Variety of Green

then of other Colours?

ITt is because it is the figure of

Youth wherin nature would

provide as many green, as youth

hath affections; and so present a

Sea-green for profuse wasters in

voyages; a Grasse-green for sud-

den new men enobled from Grasi-

ers; and a Goose-green for such

Polititians as pretend to preserve

the Capitol. Or else Propheti-

cally foreseeing an age, wherein

they shall all hunt. And for such

as misdemeane themselves a Willo-

green; For Magistrates must as-

well have Fasces born before

them to chastize the small offen-

ces, as Secures to cut off the great.

44

PROBLEMES.

V.

44

PROBLEMES.

V.

Why do young Lay-men so much

study Divinity.

ISs it because others tending bu-

sily Churches preferment, neg-

lect study? Or had the Church of

Rome shut up all our wayes, till

the Lutherans broke down their

uttermost stubborn doores, and the

Calvinists picked their inwardest

and subtlest lockes? Surely the

Devill cannot be such a Foole to

hope that he shall make this stu-

dy contemptible, by making it

common. Nor that as the Dwel-

lers by the River Origus are said

(by drawing infinite ditches to

sprinkle their barren Country) to

have exhausted and intercepted

their main channell, and so lost

their more profitable course to

the sea; so we, by providing eve-

ry ones selfe, divinity enough for

his own use, should neglect our

Teachers and Fathers. He can-

not hope for better heresies then

hee hath had, nor was his King-

PROBLEMES.

45

PROBLEMES.

45

dome ever so much advanced by

debating Religion (though with

some aspersions of Error) as by a

dull and stupid security, in which

many gross things are swallowed.

Possible out of such an ambition

as we have now, to speake plainly

and fellow-like with Lords and

Kings, we thinke also to acquaint

our selves with Gods secrets: or

perchance when we study it by

mingling humane respects, It is

not Divinity.

VI.

Why hath the common Opinion af-

forded Women Soules?

ITt is agreed that we have not so

much from them as any part of

either our mortal soules of sense

or growth; and we deny soules to

others equall to them in all but

in speech for which they are be-

holding to their bodily instruments

For perchance an Oxes heart, or

a Goates, or a Foxes, or a Serpents

would speake just so, if it were in

46

PROBLEMES.

46

PROBLEMES.

the breast, and could move that

tongue and jawes. Have they so

many advantages and means to

hurt us (for, ever their loving de-

stroyed us) that we dare not dis-

please them, but give them what

they will? And so when some call

them Angels, some Goddesses, and

the Palpulian Hereticks made

them Bishops, we descend so much

with the stream, to allow them

Soules? Or do we some-

what (in this dignifying of them)

flatter Princes and great Per-

sonages that are so much gover-

ned by them? Or do we in that

easiness and prodigality, wherein

we daily lose our own souls to

we care not whom, so labour

to perswade our selves, that sith

a woman hath a soul, a soul is no

great matter? Or do we lend

them souls but for use, since they

for our sakes, give their souls

again, and their bodies to boot?

Or perchance because the Devil

(who is all soul) doth most

mischief, and for convenience

and proportion, because they

PROBLEMES.

47

PROBLEMES.

47

would come nearer him, we al-

low them some souls; and so as

the Romans naturalized some

Provinces in revenge, and made

them Romans, only for the bur-

then of the Common-wealth;

so we have given women souls on-

ly to make them capable of dam-

nation?

VII.

Why are the fairest falsest.

I Mmean not of fals Alchimy beau-

ty, for then the question should

be inverted, Why are the falsest

fairest? It is not only because

they are much solicited and sought

for, so is gold, yet it is not so com-

mon; and this suit to them, should

teach them their value, and make

them more reserved. Nor is it

because the delicatest blood hath

the best spirits, for what is that to

the flesh? perchance such constitu-

tions have the best wits, and there is

48

PROBLEMES.

48

PROBLEMES.

no proportionable subject, for wo-

mens wit, but deceit? doth the

minde so follow the temperature

of the body, that because those

complexions are aptest to change,

the mind is therefore so? Or as

Bels of the purest metal retain

their tinkling and sound largest;

so the memory of the last pleasure

lasts longer in these, and dispo-

seth them to the next: But sure

it is not in the complexion, for

those that do but think themselvs

fair, are presently inclined to

this multiplicity of loves, which

being but fair in conceit are false

in deed: and so perchance when

they are born to this beauty, or

have made it, or have dream'd it,

they easily believe all addresses

and applications of every man, out

of a sense of their own worthi-

ness to be directed to them, which

others less worthy in their own

thoughts apprehend not, or dis-

credit. But I think the true rea-

son is, that being like gold in many

properties (as that all snatch at

them, but the worst possess them,

PROBLEMES.

49

PROBLEMES.

49

that they care not how deep we

dig for them, and that by the

Law of nature, Occupandi conce-

ditur) they would be like also in

this, that as Gold to make it self

of use admits allay, so they, that

they may be tractable, mutable,

and currant, have to their allay

Falshood.

VIII.

Why Venus-star only doth cast a

shadow?

ISs it because it is nearer the

earth? But they whose profes-

sion it is to see that nothing be

done in heaven without their

consent (as Re--- says in him-

self of Astrologers) have bid Mer-

cury to be nearer. Is it because

the works of Venus want shadowing,

covering, and disguising? But those

of Mercury need it more; for Elo-

quence, his occupation, is all sha-

dow and colours; let our life be a

sea, and then our reason and even

50

PROBLEMES.

50

PROBLEMES.

onspassions are winde enough to carry us

whether we should go, but Elo-

quence is a storm and tempest

that miscarries: and who doubts

that Eloquence which must per-

swade people to take a yoke of

soveraignty (and then beg and

make Laws to tye them faster,

and then give money to the in-

vention, repair and strengthen it)

needs more shadows and colou-

ring, then to perswade any man

or woman to that which is natu-

ral. And Venus markets are so

natural, that when we solicite

the best way (which is by marri-

age) our perswasions work not so

much to draw a woman to

us, as against her nature

to draw her from all other be-

sides. And so when we go a-

gainst nature, and from Venus-

work (for marriage is chastitie)

we need shadowes and colours,

but not else. In Seneca's time it

was a course, an un-Roman and a

contemptible thing even in a

Matron, not to have had a Love

PROBLEMES.

51

PROBLEMES.

51

beside her husband, which

though the Law required not at

their hands, yet they did it zea-

lously out of the Councel of

Custom and fashion, which was

venery of supererrogation:

Et te spectator plusquam de-

lectat Adulter,

saith Martial: And Horace, be-

cause many lights would not shew

him enough, created many Ima-

ges of the same Object by wain-

scoting his chamber with looking-

glasses: so that Venus flies not

light, so much as Mercury, who

creeping into our understanding,

our darkness would be defeated,

if he were perceived. Then ei-

ther this shadow confesseth that

same dark Melancholy Repen-

tance which accompanies; or

that so violent fires, needs some

shadowy refreshing and inter-

mission: Or else light signifying

both day and youth, and shadow

both night and age, she pronoun-

ceth by this that she professeth

both all persons and times.

52

PROBLEMES.

IX.

52

PROBLEMES.

IX.

Why is Venus-star multinominous,

called both Hesperus and Vesper.

THhe Moon hath as many

names, but not as she is a

star, but as she hath divers go-

vernments; but Venus is multi-

nominous to give example to her

prostitute disciples, who so often,

either to renew or refresh them

selves towards lovers, or to

disguise themselves from Magi-

strates, are to take new names.

It may be she takes new names af-

ter her many functions, for as she

is supream Monarch of all Suns

at large (which is lust) so is she

joyned in Commission with all

Mythologicks, with Juno, Diana,

and all others for marriage. It

may be because of the divers

names to her self, for her affecti-

ons have more names than any

vice: scilicet, Pollution, Fornica-

tion, Adultery, Lay-Incest, Church-

Incest, Rape, Sodomy, Mastupra-

PROBLEMES.

53

tion, Masturbation, and a thou-

PROBLEMES.

53

tion, Masturbation, and a thou-sand others. Perchance her di-

vers names shewed her applia-

bleness to divers men, for Nep-

tune distilled and wet her in love,

the Sun warms and melts her,

Mercury perswaded and swore

her, Jupiters authority secured,

and Vulcan hammer'd her. As

Hesperus she presents you with

her bonum utile, because it is whol-

somest in the morning: As Vesper

with her bonum delectabile, because

it is pleasantest in the evening.

And because industrious men rise

and endure with the Sun in their

civil businesses, this Star cals them

up a little before, and remem-

bers them again a little after for

her business; for certainly,

Venit Hesperus, ite capellæ:

was spoken to Lovers in the per-

sons of Goats.

54

PROBLEMES.

X.

54

PROBLEMES.

X.

Why are new Officers least oppres-

sing?

MUust the old Proverb, that

Old dogs bite sorest, be

true in all kinde of dogs? Me

thinks the fresh memory they

have of the money they parted

with for the place, should hasten

them for the re-imbursing: And

perchance they do but seem ea-

sier to their suiters; who (as all

other Patients) do account all

change of pain, easie. But if it

be so, it is either because the so-

dain sense and contentment of the

honor of the place, retards and

remits the rage of their profits,

and so having stayed their sto-

macks, they can forbear the se-

cond course a while: Or having

overcome the steepest part of the

hill, and clambered above Com-

petitions and Oppositions they

dare loiter, and take breath: Per-

chance being come from places,

PROBLEMES.

55

PROBLEMES.

55

where they tasted no gain, a lit-

tle seems much to them at first,

for it is long before a Christian con-

science overtakes, or straies into an

Officers heart. It may be that

out of the general disease of all

men not to love the memory of a

predecessor, they seek to disgrace

them by such easiness, and make

good first impressions, that so ha-

ving drawn much water to their

Mill, they may afterwards grind

at ease: For if from the rules of

good horsemanship, they thought

it wholsome to jet out in a mode-

rate pace, they should also take

up towards their journeys end,

not mend their pace continually,

and gallop to their Inns-dore, the

grave; except perchance their con-

science at that time so touch them

that they think it an injury & da-

mage both to him that must sell,

and to him that must buy the Of-

fice after their death, and a kind

of dilapidation if they by conti-

nuing honest should discredit the

place, and bring it to a lower

rent, or under-value.

56

PROBLEMES.

XI.

56

PROBLEMES.

XI.

Why doth the Poxe soe much affect

to undermine the Nose?

PAaracelsus perchance saith

true, That every Disease hath

his Exaltation in some part cer-

taine. But why this in the Nose?

Is there so much mercy in this di-

sease, that it provides that one

should not smell his own stinck?

Or hath it but the common for-

tune, that being begot and bred

in obscurest and secretest places,

because therefore his serpentine

crawling and insinuation should

not be suspected, nor seen, he

comes soonest into great place,

and is more able to destroy the

worthiest member, then a Di-

sease better born? Perchance as

mice defeat Elephants by knaw-

ing their Proboscis, which is

their Nose, this wretched Indian

Vermine practiseth to doe the

same upon us. Or as the ancient

furious Custome and Connivency

of some Lawes, that one might cut

off their Nose whome he depre-

PROBLEMES.

57

hended in Adulterie, was but a

PROBLEMES.

57

hended in Adulterie, was but a

Tipe of this; And that now more

charitable lawes having taken a-

way all Revenge from particular

hands, this common Magistrate

and Executioner is come to doe

the same Office invisibly? Or

by withdrawing this conspicu-

ous part, the Nose, it warnes us

from all adventuring upon that

Coast; for it is as good a marke

to take in a flag as to hang one

out. Possibly heate, which is more

potent and active then cold,

thought her selfe injured, and the

Harmony of the world out of

tune, when cold was able to shew

the high-way to Noses in Musco

via, except she found the meanes

to doe the same in other Coun-

tries. Or because by the consent of

all, there is an Analogy, Proporti-

on and affection between the Nose

and that part where this disease is

first contracted, and therefore He-

liogabalus chose not his Minions

in the Bath but by the Nose; And

Albertus had a knavish meaning

when he preferd great Noses;

58

PROBLEMES.

58

PROBLEMES.

And the licentious Poet was Na-

so Poeta. I think this reason is

nearest truth, That the Nose is

most compassionate with this

part: Except this be nearer, that

it is reasonable that this Disease

in particular should affect the

most eminent and perspicuous

part, which in general doth af-

fect to take hold of the most e-

minent and conspicuous men.

XII.

Why die none for Love now?

BEecause women are become ea-

syer. Or because these la-

ter times have provided mankind

of more new means for the de-

stroying of themselves and one

another, Pox, Gunpowder, Young

marriages, and Controversies in

Religion. Or is there in true Hi-

story no Precedent or Example

of it? Or perchance some die

so, but are not therefore worthy

the remembring or speaking of?

PROBLEMES.

59

XIII.

PROBLEMES.

59

XIII.

Why do Women delight much in

Feathers?

THhey think that Feathers imi-

tate wings, and so shew their

restlessness and instability. As

they are in matter, so they would

be in name, like Embroiderers,

Painters, and such Artificers of

curious vanities, which the vul-

gar call Pluminaries. Or else

they have feathers upon the same

reason, which moves them to

love the unworthiest men, which

is, that they may be thereby ex-

cusable in their inconstancy and

often changing.

XIV.

Why doth not Gold soyl the fingers?

DOoth it direct all the venom

to the heart? Or is it because

bribing should not be discover-

ed? Or because that should pay

purely, for which pure things

are given, as Love, Honor, Justice

60

PROBLEMES.

60

PROBLEMES.

and Heaven? Or doth it seldom

come into innocent hands, but in-

to such as for former foulness you

cannot discern this?

XV.

Why do great men of all dependants,

chuse to preserve their little Pimps?

ITt is not hecause they are got

nearest their secrets, for they

whom they bring come nearer.

Nor because commonly they and

their bawds have lain in one belly,

for then they should love their

brothers aswel. Nor because they

are witnesses of their weakness,

for they are weak ones. Either it is

because they have a double hold

and obligation upon their masters

for providing them surgery and

remedy after, aswel as pleasure be-

fore, and bringing them always

such stuff, as they shal always need

their service? Or because they

may be received and enter-

tained every where, and Lords

fling off none but such as they

PROBLEMES.

61

PROBLEMES.

61

may destroy by it. Or perchance

we deceive our selves, and every

Lord having many, and, of neces-

sity, some rising, we mark

only these.

XVI.

why are Courtiers sooner Atheists

then men of other conditions?

ISs it because as Physitians con-

templating Nature, and finding

many abstruse things subject to

the search of Reason, thinks ther-

fore that all is so; so they (seeing

mens destinies, mad at Court,

neck out and in joynt there, War,

Peace, Life and Death derived

from thence) climb no higher? Or

doth a familiarity with greatness,

and daily conversation and ac-

quaintance with it breed a con-

tempt of all greatness? Or because

that they see that opinion or need

of one another, and fear makes

the degrees of servants, Lords

and Kings, do they think

that God likewise for such

62

PROBLEMES.

62

PROBLEMES.

Reason hath been mans Creator?

Perchance it is because they see

Vice prosper best there, and, bur-

thened with sinne, doe they not,

for their ease, endeavour to put

off the feare and Knowledge of

God, as facinorous men deny

Magistracy? Or are the most A-

theists in that place, because it is

the foole that said in his heart,

There is no God.

XVII.

Why are statesmen most incre-

dulous?

ARre they all wise enough to

follow their excellent Pat-

tern Tiberius, who brought the

senate to be diligent and industri-

onus to believe him, were it never

so opposite or diametricall, that

it destroyed their very ends to be

believed, as Asinius Gallus had

almost deceived this man by be-

lieving him, and the Major and

Aldermen of London in Richard

the Third? Or are businesses (a-

PROBLEMES.

63

bout which these men are con-

PROBLEMES.

63

bout which these men are con-versant) so conjecturall, so sub-

ject to unsuspected interventions

that they are therefore forc'd to

speake oraculously, whisperingly,

generally, and therefore escap-

ingly, in the language of Alma-

nack-makers for weather? Or

are those (as they call them)

Arcana imperii, as by whom the

Prince provokes his lust, and by

whom he vents it, of what Cloath

his socks are, and such, so deep,

and so irreveald, as any error in

them is inexcusable? If these

were the reasons, they would not

only serve for state-business. But

why will they not tell true, what

a Clock it is, and what weather,

but abstain from truth of it, if it

conduce not to their ends, as

Witches which will not name Je-

sus, though it be in a curse? ei-

there they know little out of

their own Elements, or a Custom

in one matter begetts an habite

in all. Or the lower sort imitate

Lords, they their Princes, these

their Prince. Or else they be

64

PROBLEMES.

64

PROBLEMES.

lieve one another, and so never

hear truth. Or they abstain

from the little Channel of truth,

least, at last, they should finde the

fountain it self, God.

The true Character of a Scot

56

The Character of

The true Character of a Scot

56

The Character of

a Scot at the first

sight.

ATt his first ap-

pearing in the

Charterhouse, an

Olive colou-

red Velvet suit

owned him,

which since became mous-colour,

A pair of unskour'd stockings-

gules, One indifferent shooe, his

band of Edenburgh, and cuffs of

London, both strangers to his

shirt, a white feather in a hat that

had bin sod, one onely cloak for

the rain, which yet he made serve

him for all weathers: A Barren-

half-acre of Face, amidst where-

of an eminent Nose advanced

66

at the first sight.

66

at the first sight.

himself, like the new Mount at

Wansted, over-looking his Beard,

and all the wilde Countrey there-

abouts; He was tended enough,

but not well; for they were cer-

tain dumb creeping Followers,

yet they made way for their Ma-

ster, the Laird.---At the first pre-

sentment his Breeches were his

Sumpter, and his Packets, Trunks,

Cloak-bags, Portmanteau's and

all; He then grew a Knight-

wright, and there is extant of his

ware at 100l. 150l. and 200l.

price. Immediately after this,

he shifteth his suit, so did his

Whore, and to a Bear-baiting

they went, whither I followed

them not, but Tom. Thorney did.

67

The True Chara-

67

The True Chara-cter of a Dunce.

HEe hath a Soule

drownd in a lump

of Flesh, or is a

piece of Earth that

Prometheus put not

half his proportion of Fire into,

a thing that hath neither edge of

desire, nor feeling of affection in

it, The most dangerous creature

for confirming an Atheist, who

would straight swear, his soul

were nothing but the bare tem-

perature of his body: He sleeps

as he goes, and his thoughts sel-

dom reach an inch further then

his eyes; The most part of the

faculties of his soul lye Fallow,

or are like the restive Jades that

no spur can drive forwards to-

8666

The true Character of a Dunce.

wards the pursuite of any worthy

8666

The true Character of a Dunce.

wards the pursuite of any worthy

design; one of the most unprofita-

ble of all Gods creatures, being as

he is, a thing put clean besides his

right use, made fitt for the cart &

the flail, and by mischance Entan-

gled amongst books and papers, a

man cannot tel possible what he

is now good for, save to move up

and down and fill room, or to serv

as Animatum Instrumentum for

others to work withal in base Im-

ployments, or to be a foyl for bet-

ter witts, or to serve (as They say

monsters do) to set out the variety

of nature, and Ornament of the

Universe, He is meer nothing of

himself, neither eates, nor drinkes,

nor goes, nor spits but by imita-

tion, for al which, he hath set forms

& fashions, which he never varies,

but sticks to, with the like plod-

ding constancy that a milhors fol-

lows his trace, both the muses and

the graces are his hard Mistrisses,

though he daily Invocate them,

though he sacrifize Hecatombs,

they stil look a squint, you shall

note him oft (besides his dull eye

The true Character of a Dunce.

69

The true Character of a Dunce.

69

and louting head, and a certain

clammie benum'd pace) by a fair

displai'd beard, a Nightcap and a

gown, whose very wrincles pro-

claim him the true genius of for-

mality, but of al others, his discours

and compositions best speak him,

both of them are much of one stuf

& fashion, he speaks just what his

books or last company said unto

him without varying one whit &

very seldom understands himself,

you may know by his discourse

where he was last, for what he read

or heard yesterday he now dis-

chargeth his memory or notebook

of, not his understanding, for it ne-

ver came there; what he hath he

flings abroad at al adventurs with-

out accomodating it to time, place

persons or occasions, he commonly

loseth himself in his tale, and flut-

ters up and down windles without

recovery, and whatsoever next pre-

sents it self, his heavie conceit sei-

zeth upon and goeth along with,

however Heterogeneal to his mat-

ter in hand, his jests are either old

flead proverbs, or lean-starv'd-

70

The true Character of a Dunce.

70

The true Character of a Dunce.

hackny-Apophthegm's, or poor verball

quips outworn by Servingmen,

Tapsters and Milkmaids, even

laid aside by Balladers, He as-

sents to all men that bring any

shadow of reason, and you may

make him when he speaks most

Dogmatically, even with one

breath, to averr pure contra-

dictions, His Compositions differ

only terminorum positione from

Dreams, Nothing but rude heaps

of Immaterial-inchoherent dros-

sie-rubbish-stuffe, promiscuous-

ly thrust up together, enough

to Infuse dullness and Barrenness

of Conceit into him that is so

Prodigall of his eares as to give

the hearing, enough to make a

mans memory Ake with suffering

such dirtie stuffe cast into it, as

unwellcome to any true conceit,

as Sluttish Morsells or Wallo-

wish Potions to a Nice-Stomack

which whiles he empties himselfe

of, it sticks in his Teeth nor can

he be Delivered without Sweate

and Sighes, and Humms, and

Coughs enough to shake his

The true Character of a Dunce.

71

The true Character of a Dunce.

71

Grandams teeth out of her head;

Heel spitt, and scratch, and yawn,

and stamp, and turn like sick men

from one elbow to another, and

Deserve as much pitty during

this torture as men in Fits of Ter-

tian Feavors or selfe lashing Peni-

tentiaries; in a word, Rip him

quite asunder, and examin every

shred of him, you shall finde him

to be just nothing, but the sub-

ject of Nothing, the object of

contempt, yet such as he is you

must take him, for there is no

hope he should ever become bet-

ter.

72

An Essay of Valour.

72

An Essay of Valour.

I Aam of opinion that

nothing is so potent

either to procure or

merit Love, as Va-

lour, and I am glad I am so, for

thereby I shall do my self much

ease, because Valour never needs

much wit to maintain it: To speak

of it in it self, It is a quality

which he that hath, shall have

least need of, so the best League

between Princes is a mutual fear

of each other, it teacheth a man

to value his reputation as his life,

and chiefly to hold the Lye un-

sufferable, though being alone,

he finds no hurt it doth him, It

leaves it self to others censures,

for he that brags of his own va-

lour, disswades others from be-

An Essay of Valour.

73

An Essay of Valour.

73

lieving it, It feareth a word no

more then an Ague, It always

makes good the Owner, for