ArchBook: Architectures of the Book

Published February 1, 2017

Corrected and updated April 1, 2019

Search techniques define the limits of the searchable. The concordance illustrates this dynamic better than most other search tools in the history of information technology. In the preface to his 1737 concordance to the Bible, Alexander Cruden defined the tool as "a Dictionary, or an Index to the Bible, wherein all the words used throughout the inspired writings are ranged alphabetically, and all the various places where they occur are referred to, to assist us in finding out passages, and comparing the several significations of the same word."1 While accurate technically, Cruden's domain-specific definition remains unsatisfying because it fails to anticipate the elements that secure the tool's place in intellectual history: its use for literary study and the way its logic underlies the functions of modern information technology.

In the most basic terms, a concordance compiles and organizes all occurrences of each word within a text of interest, allowing the reader to efficiently seek and retrieve each instance of whatever word she or he requires. In this sense, the tool is much like the modern-day index, except that due to their large size, concordances were generally bound on their own, separate from their source texts. Given the tremendous amount of labor required, the first medieval concordances failed to provide related and surrounding words for each entry,2 though thirteenth-century scholars quickly addressed this shortcoming. This added context perfectly fit the scholarly spirit of the age, encouraging the thematic organization of sermons as well as the further theoretical distinctions between theological concepts. Furthermore, the organization of keywords within their context would come to inspire twentieth-century computer scientist H. P. Luhn to build a system for organizing new research literature via keywords to facilitate expedient skimming, thereby forever binding the medieval information technology to its contemporary successor, the Internet search engine.3

In making texts searchable in the first place, concordances inspired new practices of reading and composition, including sermon writing, non-linear reading, and more accurate methods of theological and academic study. Since its heyday in medieval Western manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC culture, the concordance has offered its users the promise of more efficient and complete access to important works.4

The concordance was first widely used in connection with theological study, but since the mid-eighteenth century, it has been adapted for literary and other scholarly purposes. Starting with Shakespeare, the study of most major canonical literary figures is now aided by dedicated concordances. This achievement highlights a major criticism of the tool itself: concordances tend to privilege a corpus divorced from its surroundings, thus overlooking aspects of etymology and intertextuality. Few literary concordances make any reference between authors, leading even ardent supporters of the concordance to stress the fact that "concording a text is neither ideologically innocent nor…methodologically objective."5 To that end, a new generation of scholars are currently reevaluating and theorizing the uses for data gleaned from concordances.

Indeed, relatively recent advances in computation have revolutionized the project and purpose of this nearly eight-hundred-year-old tool. Shortly after the Second World War, Italian Jesuit Priest Roberto Busa teamed with IBM to build an eleven million-word Latin concordance of the works of Thomas Aquinas—a historical event which many point to as the birth of digital humanities, or, more properly, humanities computing.6 What once took the labor of a team of five hundred monks, twenty-six years of an obsessive man's life, or even cutting-edge computing technology, can now be produced on demand for undergraduate term papers.

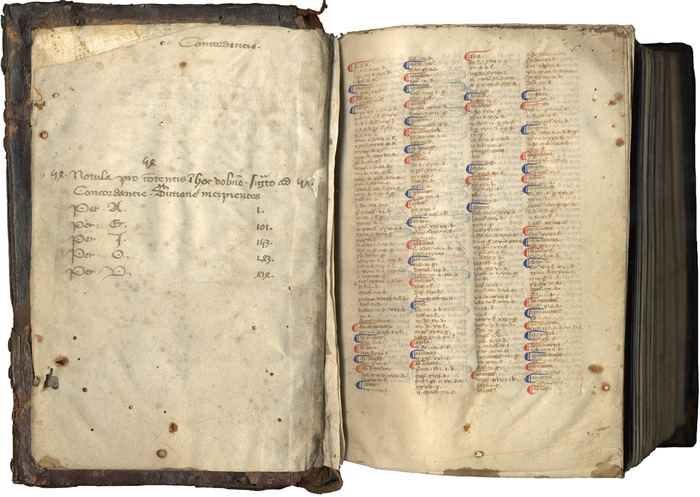

The material history of the concordance can be traced to the 1230s with Hugh of Saint Cher, Friar and leader of a Dominican order famous for "devising, adopting, and adapting" techniques to further their scriptural studies and manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC production.7 The concordance as an idea, however, can be traced back even further, to lists and tables drawn up by Jewish Masoretes at the end of the Masora (the Hebrew text of the Jewish Bible) around the tenth century CE.8 The work of Hugh, along with his team of three hundred to five hundred monks, eventually culminated in the "St. Jacques Concordance" (fig. 1) to the Latin scriptures of the Vulgate Bible, which allowed students to trace scriptural references across multiple locations. Comprised only of single keywords, as opposed to full citations to give context, the St. Jacques Concordance resembles the related index verborum (a tool that helps point out the correct instance of a desired word, fig. 2) and the common place index, an alphabetic list pointing to the passage where the word was found.

Figure 1

Click For Larger Image

Hugh of St. Cher’s St. Jacques Concordance: Concordantie super bibliam [Verbal Concordance of the Scriptures]. In Latin, manuscript on parchment. [France, Abbey of Saint-Jacques?, c. 1250]. This image represents one of just twenty-two surviving manuscript copies of the St. Jacques Concordance. Here you see the short length of each entry, only giving letters that correspond to passages, much like the larger image from Index Verborum Vergilianus (fig.2). Image courtesy of Les Enluminures.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 2

Click For Larger Image

Index Verborum Vergilianus by Monroe Nichols Wetmore (Yale UP, 1911). An alphabetized list of Latin words from the works of Virgil. Image courtesy of the Internet Archive.CLOSE or ESC

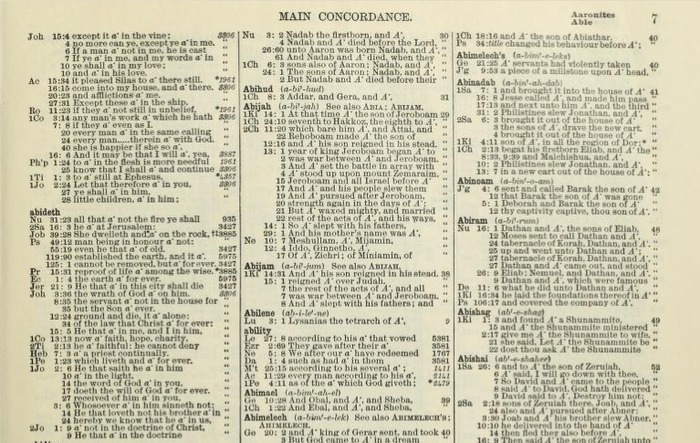

Hugh's St. Jacques Concordance resembles the index that one might find at the end of a contemporary scholarly book, only more rudimentary. A typical modern concordance, on the other hand, lists every occurrence of the word as well as short quotations illustrating the word in context to help direct the reader to the line in question, instead of just the page of each reference (fig. 3).

Figure 3

Click For Larger Image

1890 edition of Robert Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance. Note the length and contents of each entry. "Abideth," for example, takes up nearly half a column. This particular page provides surrounding context for fifteen words (mostly names). In comparison, the analogous page of the St. Jacques Concordance surveys over fifty words. Image courtesy of the Internet Archive.CLOSE or ESC

To fully appreciate the impact of the work of Hugh's monks, one must keep in mind that alphabetization was rare at this point; most theologians believed that man had no right to sort scripture for his convenience, favoring instead the "rational" method of arranging information according to divine order.9 For example, this system required references to God to be listed first. Indeed, preaching in any other succession symbolized an affront to the traditional organization of scripture.10 Nevertheless, a "burgeoning need to find"11 stimulated by the collection of biblical distinctions and alphabetical classification systems supported the growing popularity and import of scholarly tools over the course of the thirteenth century. In fact, by the fourteenth century, preachers were expected to have access to a concordance while composing their sermons.12

The monks of Hugh's order alphabetized the over ten thousand words of the Latin Bible into columns, much like a modern dictionary. After each word, the monks listed each occurrence of it in sequential order. Each reference included Bible book, chapter, and letter (A through G).13 Not surprisingly, this referencing system was not precise enough to make the concordance efficient for use in composing sermons. In the middle of the century (1250-1252), English Dominicans added quotations.14

Contemporary accounts remind us that Hugh's work should only be considered a starting point for the tool's history. The concordance required a more efficiently organized and structured source text to be of any real use. After Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, first introduced chapter divisions to the Bible in the early thirteenth century, "marginal alphabets" were used to break chapters into smaller parts, since verse division had not yet been devised.15 Historians attribute the first systematic attempt at this method to the monks of Hugh's order. Their "Dominican index system" required the reader to mentally divide each chapter and provide a letter corresponding to its relative placement in that chapter, trusting the concordance's producer to have made the same calculation.16

Organizational innovation proceeded rapidly up until and beyond Gutenberg. In the late thirteenth century, an English Dominican, Richard of Stavensby, succeeded in adding at least a sentence of context for each entry in the index. Extant fourteenth-century concordances indicate that their authors were working towards further integrating contextual information, as demonstrated by the move to include full sentences rather than simply listing single words.17 In 1310, Conrad of Halberstadt compressed the size of the concordance by indicating only a selected portion of text, and thus, a modern version of the concordance finally became viable.18 By the fourteenth century, a scholarly book was considered incomplete if it lacked an index.19

Personal Exegesis

Commercial, religious, and political transformations brought on by the Reformation and the spread of movable type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC created a market for Bible study tools in the vernacular, thus allowing the concordance to reach a larger variety of audiences. Rabbi Isaac Nathan ben Kalonymus had already produced the first concordance of the Hebrew Old Testament in 1448.20 Thomas Gybson completed the first English language concordance to the New Testament, impressively titled The Concordance of the New Testament most necessary to be had in the hands of all soche as delight in the communication of any place contained in the new Testament, between 1535 and 1540.21 Shortly thereafter, John Marbeck attempted to expand this treatment to the Old Testament. Marbeck's concordance marks an important milestone: for the first time, the concordance began to be regarded as a tool for personal exegesis, to be used by the lay and the clergy alike. Marbeck was accused of heresy for this transgression, and, not coincidentally, his work was lost to fire, even though he had adorned his title page with images of the King Edward VI in council—an attempt to make the text appear both authoritative and universal.22 Marbeck's work threatened the Church, not just because it detached the word of God from specialized interpretation, but because it simultaneously endangered Latin's supremacy. Despite a death sentence (for which he was later pardoned), Marbeck completed a slightly abridged version in 1550.23

The following years witnessed the ascension of two extremely popular versions of the English language Bible—the Geneva Version ("the Bible of Shakespeare and the Pilgrims"24 ) and the King James Version (KJV). The introduction of modern verse divisions into the Geneva Bible by Robert Stephanus25 simplified concordance usage and thereby increased its popularity. Samuel Newman's A large and compleat concordance to the Bible of the last Translation (1634), the landmark concordance of the King James Version during this period, marked the most comprehensive work in English to date, though it still fell short of all contemporary standards for completeness. Due to time and space constraints, Newman left out many proper nouns, prepositions, and errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC, and thus did not ensure that "every word is cited and at least one passage is indicated for the word."26 Concordances continued to grow in size, authority, and popularity. Robert F. Herrey's 1578 concordance was even bound with the Geneva Bible.27 Multifaceted aids to biblical reading became standard supplements to Bibles written in the vernacular. Armed with new navigational technologies like pagination Pagination the numbering of pages. See: Foliation Page CLOSE or ESC (introduced by Erasmus in 1516) and verse divisions (introduced by Robert Estienne in 1555), the concordance continued to become a more widely accessible search tool.28

Work Enough to Drive One Mad

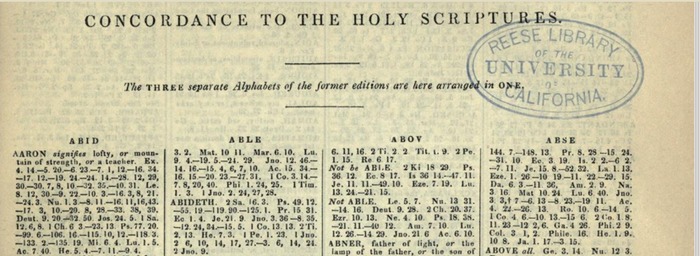

While many intriguing personalities populate the history of the concordance, Alexander Cruden was its mad genius. Cruden dedicated most of his adult life to completing an exhaustive concordance of the KJV Bible and its Apocrypha; his work remains, arguably, the most important and popular English language concordance (fig. 4), though not necessarily the most useful. In print continuously since its original publication in 1737, the work remains relevant to historians, scholars, and theologians today, so much so that the University of California offers on-demand reprint editions of the text.

Figure 4

Click For Larger Image

1849 (?) edition of Cruden’s Complete Concordance to the Bible arranged under one alphabet published by S. Bagster and Sons, London. Notice that Cruden advertises the collapse of three separate languages from former editions into one. Unlike Strong’s later exhaustive concordance, however, these three languages were jumbled together in alphabetical order, not side-by-side to aid comparison. Image courtesy of the Internet Archive.CLOSE or ESC

The biographical details of Cruden's life secure his place in history. After quickly rising in the bookselling trade, he obtained special licensing rights as bookseller to the Queen. From then on, he dedicated himself solely to compiling a concordance to all the words in the KJV Bible, for which no "complete" concordance had yet been produced.29 The undertaking took twenty-six years of eighteen-hour days to index 774,746 words into an almost 2,370,000 word opus.30 The sheer magnitude of this labor does not only sound unbelievable, it sounds crazy, and Cruden's society seems to have concurred. Cruden's herculean labors took their toll, and he was institutionalized multiple times.31 His landmark work, however, changed the face of Bible study and "made 'concordance' a household word."32

As Cruden's concordance attracted wider use, the need for analytical (or multilingual) concordances—in Greek, Hebrew, and English, for example—arose. Robert Young was among the first to embark on such an undertaking, producing in 1879 a concordance which allowed its user to compare Greek, Hebrew, and English citations side by side. Dr. James Strong published his competing "exhaustive" concordance in 1890 (fig. 3), using Greek and Hebrew roots to aid its user's search through the connections between every single word in the English KJV Bible.33

Literary Scholarship

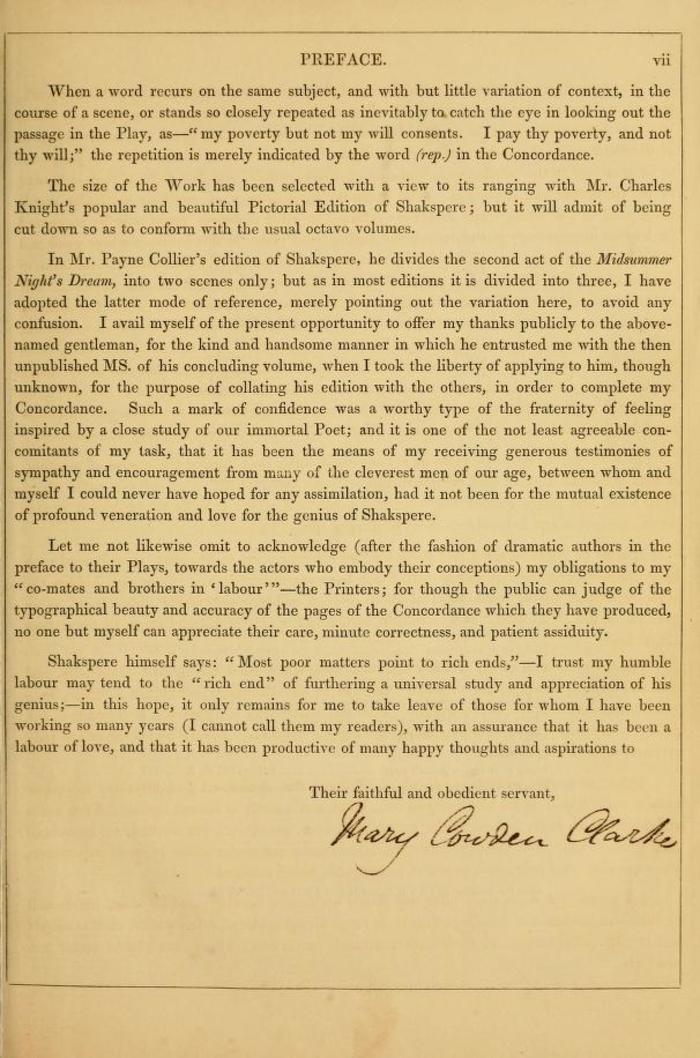

Religious use clearly dominates the history of the concordance, but use of the tool is by no means exclusive to theological research. In 1845, Mary Cowden Clarke completed her concordance on the complete works of Shakespeare (fig. 5), what she referred to as the "Bible of the Intellectual World,"34 adopting theological language to justify her intensive effort. Clarke's participation in the emergent "cult of the Bard" demonstrates, once again, the shifting nature of textual scholarship as well as a desire for search-based information technology for texts. Clarke's work sparked interest in producing complete concordances for other canonical English authors, such as Milton and Pope, and they continued to be regularly published throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—primarily the twentieth,35 on many authors, ranging from Homer and the ancients to Matthew Arnold to Marlowe to Melville, and finally Byron, the subject of "the last handmade concordance" in 1965.36 Notwithstanding all the hard work required to make them, literary concordances have yet to approach anywhere near the demand and popularity of scriptural concordances.

Figure 5

Click For Larger Image

Preface to Mary Cowden Clarke’s Concordance to the Works of Shakspere. Image courtesy of the Internet Archive.CLOSE or ESC

As literary scholarship became institutionalized in the early twentieth century through the appointment of faculty in what we now think of as English literature departments, so did the concordance. Indeed, the Concordance Society was born in 1906 in an attempt to address the need to professionalize methods for literary scholarship because, as Lane Cooper argued at the time, "the best of our modern poets deserve the kind of study that for generations have been lavished upon the poetry of the ancients."37 According to Cooper, the use of the literary concordance is "dual" since the "right sort of index tells us both what the poet chose to utter, and what he unconsciously or purposely refrained from uttering."38 Scholars could now turn their attention towards interpretative strategies that privileged style, using these concordances to make claims about language choice, tropes, and linguistic issues throughout an author's entire body of work.

The most important criticism of the concordance as a tool comes from textual bibliography. Literary editions are usually smaller and more disparate than scripture, and thus the choices of which edition to use as the basis for a concordance can engender scholarly dispute. Though the most advanced biblical concordances refer to multiple editions simultaneously, this ability would have required additional and mostly redundant labor for scholars producing handmade concordances to poetry and drama. Additionally, novels, though clearly not the focus of much concentrated academic scholarship by the early twentieth century, did not lend themselves to concordances due to their large word count. Even contemporary scholars concede that the concordance functions best as a "starting point" for larger inquiry.39

Digital Afterlife

The new kinds of digital scholarship facilitated by the logic underlying concordances might constitute the tool's most lasting achievement. In the late 1940s, in order to investigate the "metaphysics of presence" in the complete works of Thomas Aquinas, Father Roberto Busa persuaded Thomas J. Watson Sr., the president of IBM, to assist him in the construction of a digital concordance, thereby forever changing the relationship of handmade and machine-made scholarly tools in the humanities.40 Busa's Index Thomisticus, not published until the late 1970s, consists of a database of over eleven million words from Aquinas, among others, which Busa spent his lifetime compiling, text-mining, and analyzing in order to address large linguistic problems, such as patterns of word choice, namely the words used by the authors as compared to the set of known words that a writer fails to use. In sum, Busa's work on Aquinas attempted six ambitious goals: 1) an alphabetical list of words with frequencies and definitions; 2) a reverse index including frequencies; 3) a list of word forms with their frequencies arranged under their definitions; 4) a list of the relevant lemmas ("A lexical item as it is presented…in a dictionary entry");41 5) an index locorum (index of passages); and 6) "a concordance with verse line context for each word in the hymns."42 Once immense bodies of text could be efficiently gathered together and processed, Busa hoped that scholars could begin to discern larger connections and imperceptible explanations for the natural rules of poetic and communicative speech, as well as further appreciate the work of Thomas Aquinas.

Scholars appreciated the magnitude of Busa's vision from the beginning; as early as 1957, IBM researcher Paul Tasman noted that his work with Busa might signal a "new era of language engineering" by offering a "comparatively fast method of literature searching" that would generate "improved and more sophisticated techniques in libraries, chemical documents, and abstract preparation, as well as in literary analysis."43 Busa also produced a CD-ROM version of the Aquinas index cheekily now known as "cum hypertextibus" because of the ways it incorporated some hypertextual Hypertext any system which allows the connection and navigation of computer documents through links. CLOSE or ESC features.44 The complete Index Thomisticus is now available online here.

Inspired by Busa's pioneering work, others attempted to build computer-generated concordances. In the early 1950s, Reverend John W. Ellison used the UNIVAC, a famous early computer, to attempt a concordance of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible.45 In 1959, computer scientist H. P. Luhn adapted techniques used to compile concordances to design the Key Word in Context (KWIC) index format. A KWIC index organizes each word in relation to the words surrounding it, thus enabling easier alphabetization. In a sense, the KWIC index format makes automatic indexing more comprehensive and efficient at the same time. Furthermore, this format helps the searcher get more reliable results and to quickly glean the meaning of the searched-for term in relation to its surroundings. The addition of the KWIC format thus spread the underlying logic of the concordance to new tools, which helped create "a variety of indexes that could have never been produced before automation."46 Consequently, Luhn formally linked information science to the history of the book and, in the process, helped direct the evolution of search engines like Google.47

Many tout the fact that Cruden's concordance has never fallen out of print as the best evidence of the tool's continued relevance and power, but its digital afterlife makes an even stronger case. Indeed, a quick Google search returns a host of fully digital concordances including "concordances.org" and "biblez.com" that claim to render the position and relationship between every single word from twelve Bible translations immediately accessible. It is notable that historical examples like Strong's exhaustive concordance serve as the backbone for many of these digital databases.

The migration of concordance technology online has not rendered print versions obsolete. Frederick Danker maintains that, "convenience and circumstance invite use of tools that may seem antiquated next to their electronic relatives,"48 especially in the context of accuracy and reliability. The work of figures such as James Strong, Robert Young, and Alexander Cruden still provide reliable entry points for those who continue to rely upon the KJV, as do recently published print concordances for newer translations, such as the New International Version.

The lag between the promise and the realization of a new relationship between computing and textual scholarship exceeds the history of any single textual feature. The concordance, much like the field of digital humanities it helped inaugurate, finds itself at a moment of reinvention and necessary self-definition.

The Search for Presence: The Birth of the Digital Humanities

Computation in the humanities is almost as old as digital computers themselves. The story of Father Roberto Busa's calls to apply the power of machine tools to the works of Thomas Aquinas, in fact, helps paint part of a larger picture of post-war research and development, which includes some of the most influential players and institutions in the new field: Vannevar Bush of the newly created National Science Foundation (c. 1950), the National Endowment for the Humanities (c. 1965), Thomas J. Watson of IBM, as well as some of the earliest computers such as the UNIVAC.

The fact that in 1949 Busa was able to receive funding from IBM, arguably the most important company in post-War America, foreshadowed a new kind of humanities scholarship beyond the walls of universities: collaborative, funded through large institutions, and, in some ways, modeled on the tenets of scientific research. Busa's work with IBM, therefore, marks a convenient starting for the entrance of "data" into the humanist's working vocabulary. While most histories point back to Busa's work at the formation of the discipline of digital humanities, it is important to appreciate that others, including computer pioneer Andrew Booth, saw the importance of machine translation for aesthetic and interpretative problems even earlier than Busa.49 As Geoffrey Rockwell reminds us, Busa's success required wider networks of inspiration and collaboration in order to come to pass. Busa's status as the father of the digital humanities, then, seems problematic, but useful nevertheless for helping to build a narrative of the development of digital humanities, a "field" that has proven difficult to classify, let alone define.50

For those who have even briefly surveyed the emergent work in digital humanities, it becomes clear why the concordance—an instrument originally developed for scriptural navigation and research—should serve as the inaugural tool in a discipline that self-consciously highlights tool-building. The most obvious and controversial example of this emphasis comes from Stephen Ramsay's declaration at the Modern Language Association Conference of 2011: "I think Digital Humanities is about building things. I'm willing to entertain highly expansive definitions of what it means to build something…. [I]f you aren't building, you are not engaged in the ‘methodologization' of the humanities, which, to me, is the hallmark of the discipline that was already decades old when I came to it."51 There are some important implications in Ramsay's statement for the historical development of the concordance: 1) tool building in the humanities has a long history, preceding computation by centuries; 2) this history stems from both book technology and hermeneutical practice; and 3) this work was often collaborative and experimental in nature. Looking closely at the origin of the digital humanities reinforces what many of its practitioners know well—that the digital humanities needs to use the lessons learned from the history of the book in order to adequately grasp the future of reading and knowledge.52

The concordance itself has morphed in recent years of digital humanities work. More than an end product, the concordance can now best be thought of as an element within a larger system of inquiry. Indeed, the glossary of Literary Scholarship in the Digital Age—hosted at MLA Commons, the MLA's social network and online resource center—defines the concordance with reference to a computer software application of the same name. The entry explains that the program "is a comprehensive application with a number of powerful features, including multiple language support, user-definable alphabets, user-definable contexts, multiple-pane viewing, the ability to statistically analyze selected texts, and the ability to export concordance results as text, [or] HTML."53 The concordance provides a means to an end for producing dynamic approaches to reading the literary texts at hand. Furthermore, the relative ease and availability of programs like these (including free versions) make any reliable, digitized text subject to similar levels of scrutiny as widely accepted greats like Busa's Aquinas or Clarke's Shakespeare.

Two important statistical methods in the digital humanities—principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis—stem partially from the concordance as well. David Hoover explains that "cluster analysis compares the frequencies of all one hundred of the most frequent words simultaneously, determines which two texts are most similar to each other in how they use these words, and joins them into a cluster."54 It is now possible to address many lasting critiques about the use value of the concordance itself due to the newfound ability (and perhaps increased desire) to make larger statistical claims about groups of texts. Indeed, thousands of novels can be analyzed at once.

In terms of the concordance itself, Busa's work helped push the form beyond the medieval, "minimalist" approach of cross-referencing single words, to a hypothetical "interpretative" technique that puts data compiled by concordances to use in illustrating the complex logic of texts and language at work.55 Despite the immense promise of computer-aided interpretation, such methods are still clearly in their infancy, though scholars continue to experiment with techniques such as Franco Moretti's "distant reading" of large swaths of texts with the aid of statistical and algorithmic tools. Along these lines, scholars such as those working with the Literary Lab at Stanford University have begun to make claims about subjects as large as the sum of extant, digitized "nineteenth century novels," as opposed to a preselected canon of well-known texts that often stand in for the century's literary production. This method—sometimes called "quantitative formalism"56 —relies on concordance outgrowths such as PCA and cluster analysis to make greater sense of larger corpora than ever before.

The history of the concordance reflects an uneasy calculus of investment versus reward. Whereas religious audiences continue to find new approaches to making meaning from sacred texts, literary and textual scholars find themselves at a historical moment where, David Leon Higdon argues, "technology for creation of concordances has outstripped understanding of the application of concordances to literary study."57 This is another way of saying that although concordances facilitate improved search functionality, as Geoffrey Rockwell notes, "simply retrieving words doesn't give a sense of their use."58 As information retrieval techniques have become more extensive and immediate, users, including even the most discerning scholars, run the risk of putting undue trust in the accuracy of their tools. Indeed, as Charles Cooney, Glenn Roe, and Mark Olsen contend, "searching for even relatively rare terms in modern textbases can generate many thousands of occurrences. No matter how nicely they are presented in concordances or summarized in other kinds of reports, results can be difficult for a user to grasp."59 Clearly this challenge does not, in itself, undermine the value of the concordance as a tool, but rather suggests that scholars need to remain vigilant about situating their results.

Unresolved debates from the theory and canon wars resurface as well. As Cooney et al. suggest, "studies of individual terms or concepts are certainly useful, but it is difficult to generalize about their results. In particular, these scholars worry that topics like gender and ethnicity may require "different kinds of tools."60 It is reasonable to guess that these different tools could use the concordance as their basis, but only in tandem with other tools and hermeneutic strategies. As we know, the concordance has always been met with skepticism in certain scholarly circles, but now it can more easily be integrated with other approaches and be put to different ends.

Researchers such as Hoover and Ian Lancashire rely on the integration of concordance functions in their software packages to perform many different kinds of analytical and rhetorical feats. They have tried to brand this kind of inquiry as "stylistics," "corpus stylistics," and "cognitive stylistics." Hoover explains the logic behind his method in language that shares assumptions with experimental science: "exploratory tools, and concordances can also be used to test hunches… and can show which texts have unusual frequencies of words of interest."61 What's more, these tools can generate lists of words that occur repeatedly near each other.62 With this capability, scholars can survey themes and thematical variations across the work of one or many authors. This kind of digital humanities research suggests that many of the issues that have plagued concordances since their inception are being addressed by computational solutions and by integrating the power of the concordance into a larger analytical framework.

All the while, digital humanities research projects within the theological community continue to explore and develop the concordance itself. In the last few years, researchers have compiled new scriptural concordances in "Spanish, Swahili, Latvian, Russian, Portuguese (Brazil and Europe), Albanian, Solomosland Pidgin, Burmese languages, Tzotzil, Quechua, Ayamara, Kinyarwanda (Rwandan), and Chichewa."63 Considering the ways that the concordance has already been successfully integrated into a diverse set of analytical approaches, it seems that, thanks to those like Father Busa, its future will be determined by the ways humanists take advantage of computing tools built for humanities scholars by humanities scholars.

Alison, Sarah et al., "Quantitative Formalism: An Experiment." Pamphlets of the Stanford Literary Lab, 15 January 2011. https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet1.pdf

Baker, Roger G. "Baker." SBL Forum. Society of Biblical Literature. http://sbl-site.org/Article.aspx?ArticleID=518

Burton, D. M., "Automated Concordances and Word Indexes: The Fifties." Computers and the Humanities 15 (1981): 1-14.

Burton, Dolores M., "Automated Concordances and Word-Indexes: Machine Decisions and Editorial Revisions." Computers and the Humanities 16 (1982): 195-218.

Busa, Roberto, ed. Thomae Aquinatis Opera Omnia Cum Hypertextibus in CD-ROM. Milan: Editoria Elettronica Editel, 1992.

Cooney, Charles, Glenn Roe and Mark Olsen. "The Notion of the Textbase. Design and Use of Textbases in the Humanities." Literary Studies in the Digital Age. MLA Commons. http://dlsanthology.commons.mla.org/the-notion-of-the-textbase

Cooper, Lane. "The Making and the Use of a Verbal Concordance." The Sewanee Review 27.2 (Apr 1919): 188-206.

Cruden, Alexander. "Preface to the First Edition." A Complete Concordance to the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testament. London: T. Tegg and Son, 1837.

Danker, Frederick W. Multipurpose Tools for Bible Study. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1993.

Fenlon, John Francis. "Concordances of the Bible." In The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04195a.htm

Findlay, Brian. "Concordance." In The Oxford Companion to the Book, edited by Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H. R. Woudhuysen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198606536.001.0001/acref-9780198606536-e-1156.

Galey, Alan, Richard Cunningham, Brent Nelson, Ray Siemens, Paul Werstine, and the INKE Team. "Beyond Remediation: The Role of Textual Studies in Implementing New Knowledge Environments." In Digitizing Material Culture, from Antiquity to 1700, edited by Brent Nelson and Melissa Terras, 21-48. Toronto & Tempe, AZ: Iter/Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2012.

Gold, Matthew K., ed. Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Higdon, David Leon, "The Concordance: Mere Index or Needful Census?" Text: An Interdisciplinary Annual of Textual Studies 15 (2002): 48-68.

Hockey, Susan. "The History of Humanities Computing." In A Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth, 3-19. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

Hoover, David L. "Textual Analysis." Literary Studies in the Digital Age. MLA Commons. http://dlsanthology.commons.mla.org/textual-analysis/

Howard-Hill, Thomas. "The Oxford Old-Spelling Shakespeare Concordances," Studies in Bibliography 22 (1969): 143-64.

Keay, Julia. Alexander the Corrector: The Tormented Genius Whose Cruden's Concordance Unwrote the Bible. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2004.

Liu, Alan, "The End of the End of the Book: Dead Books, Lively Margins, and Social Computing." Michigan Quarterly Review 48 (2009): 499-520.

McKenzie, Kenneth. "Means and Ends in Making a Concordance, with Special Reference to Dante and Petrarch." Annual Reports of the Dante Society 25 (1906): 19-46.

Nelson, Brent, Jon Bath, and the INKE Team. "Old Ways for Linking Texts in the Digital Reading Environment: The Case of the Thompson Chain Reference Bible." Digital Humanities Quarterly 6, no. 2 (2012). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/6/2/000137/000137.html

Neville-Sington, Pamela. "Press, Politics and Religion." In The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. Volume III, 1400-1557, edited by Lotte Hellinga and J. B. Trapp, 576-607. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Powell, Daniel, with Constance Crompton and Ray Siemens. "Glossary." Literary Studies in the Digital Age. MLA Commons. http://dlsanthology.commons.mla.org/ glossary-of-terms/

Ramsay, Stephen. "Who's in and Who's Out." Stephen Ramsay (blog). January 8, 2011. http://stephenramsay.us/text/2011/01/08/whos-in-and-whos-out/.

Rees, Neil. "Dissecting the Bible." The Bible Society. https://www.biblesociety.org.uk/uploads/content/bible_in_transmission/files/2011_summer/BiT_Summer_2011_Rees.pdf

Roberts, Jane, and Pamela Robinson, eds. The History of the Book in the West: 400AD-1455. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010.

Rockwell, Geoffrey. "An Alternate Beginning to Humanities Computing." Theoreti.ca (blog). May 2, 2007 (10:51 a.m.). http://theoreti.ca/?p=1608

Rockwell, Geoffrey. "H. P. Luhn, KWIC and the Concordance." Theoreti.ca (blog). April 2, 2009 (10:51 a.m.). http://theoreti.ca/?p=2435

Rouse, Mary A., and Richard H. Rouse. "Concordances et Index." In Mise en Page et Mise en Texte du Livre Manuscrit. Edited by Henri-Jean Martin and Jean Vezin, 219-28. Paris: Éditions du Cercle De La Librairie - Promodis, 1990.

Rouse, Mary A., and Richard H. Rouse. "Statim invenire: Schools, Preachers, and New Attitudes to the Page." In Authentic Witnesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts, 191-219. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991.

Rouse, Richard H., and Mary A. Rouse. Preachers, Florilegia, and Sermons: Studies on The Manipulus Florum of Thomas of Ireland. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1979.

Smith, Margaret M. "Index." In The Oxford Companion to the Book. Volume I and II. Essays A-Z, edited by Michael F. Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Tasman, Paul. "Literary Data Processing." IBM Journal of Research and Development 1, no. 3 (1956): 249-256.

Weinberg, Bella Haas. "Predecessors of Scientific Indexing Structures in the Domain of Religion." In The History and Heritage of Scientific and Technological Information Systems, edited by W. Boyd Rayward and Mary Ellen Bowden, 126-135. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation, 2002.

Winter, Thomas Nelson, "Roberto Busa, S.J., and the Invention of the Machine-Generated Concordance." Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department, 1999. Paper 70. Republished from The Classical Bulletin 75, no. 1 (1999): 3-20. digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/70/