ArchBook: Architectures of the Book

Published May 15, 2015Corrected and updated July 10, 2019

Corrections, broadly defined, can be understood as any focused effort to remove error from written, printed, and digital texts. Textual errors are inevitable and often unpredictable; they may appear in the form of unintentional mistakes such as misspellings, misrepresented facts and names, or misplaced and missing information. Correctors may be authors, editors, printers, readers, and even, to an extent, censors. Although formally speaking “to correct” typically means “to set right,” corrections can (and often do) lead to further errors. In the process of correction, miscorrections and new errors may be introduced by authors themselves, their editors, typesetters Typesetter the person responsible for manually placing pieces of type on a forme line by line to prepare the text for print. See: Forme Type CLOSE or ESC, and even readers.

Although corrections can sometimes be chaotic—occurring as a last-minute response to the completed first-run of an edition, or as a rhetorical move to showcase the printer’s labor—the act of correction and revision progressively developed into a more methodical practice. This entry explores different types of correction, which may occur as a result of:

- editorial standards like copyediting Copyeditor the person who is responsible for reviewing proofs and making corrections. See: Proof CLOSE or ESC and proofreading, to ensure the text accurately represents the best and final draft or copy

- collation Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC and comparison, aiming at stability across multiple copies

- textual criticism, performed to identify states State variation among copies of the same edition, typically due to the correction or reintroduction of errors. See: Variant CLOSE or ESC of textual transmission or return to a (real or imaginary) “original” text

- ideological or content-based corrections, at the edges of what we might formally define as a “correction,” since they may be subjective and dependent on a particular context. These include, to an extent, acts of censorship and redactions.

Corrections have appeared in various forms (and under different names) throughout the history of writing and textual transmission, and may be structured and systematic or reactive and chaotic. Although many mechanical and formalized methods for correction were a byproduct of technologies like the printing press and, later, the computer, the identification, study, and occasional correction of errors is concurrent with the invention of writing itself: there is arguably no such thing as a perfect text.

Although errors are inherent to any form of communication, their corrections can become sites for discussion of authorial intent, collaboration, and the subsequent (intentional or accidental) textual interpretations. The study of errors and their corrections have given rise to many productive academic fields such as textual criticism, philology, and paleography. Corrections thus have the power to shift our understanding of error as a necessary yet valuable consequence of textual production.

Manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC Corrections from Antiquity through the Middle Ages

The history of textual criticism and early forms of correction are in many ways intertwined. Signs of correction have been preserved as early as the papyri of ancient Egypt. Indeed, the scholarship undertaken at the library of Alexandria continues to be carefully studied in order to bring to light early critical practices of textual transmission and preservation. Corrections in antiquity typically appear in the form of: comparison across copies (collating Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC); correction by looking at another exemplar; identification and (occasional) removal of corrupt passages; and correction by conjectural emendation. At each subsequent level of textual copying and transmission, these methods were crucial—not just for the correction of errors, but indeed for the development of accurate forms of identifying and pointing out errors for future scholars, copyists, and scribes.

Corrections in the ancient period could be performed by scribes or professional copyists, but they were also very commonly done by book owners seeking to amend a text by comparing it to another exemplar. For many of these corrections, the emendator sought to either correct or provide alternate readings for the purpose of achieving a more readable text, rather than to create an “edition” that represented the best possible copy.1 Yet it can be difficult to formally distinguish different kinds of corrections in these early manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC. For example, the Greek word διόρθωσις could alternately refer to collations Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC, corrections against an exemplar, or conjecture, as well as being more broadly used to describe an edition or publication of a text.2 Hence, it is hard to ascertain the particular goals of ancient correctors, since “in many cases they make no distinction between a correction, a variant Variant a manuscript or printed text that contains textual variations (such as different words or spelling) from another known copy; can also refer to the textual variation itself. See: State CLOSE or ESC reading, and a marginal Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC annotation.”3

To complicate matters further, scribal reproductions often led to contamination (also called “horizontal transmission”): during textual transmission (copying one manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC into another) additions and corrections were transcribed as part of the text, making it difficult if not impossible to discern how many textual traditions, correctors, and scribes had been recorded in a single witness Witness a copy or edition of a text, or a citation referring back to an original text, which can be used to reconstruct that work's composition history. CLOSE or ESC. The potential for errors was therefore great but nonetheless taken in stride. Readers seeking to own a reliable and corrected manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC copy of any given text typically had to perform “routine operations” such as “correcting slips of the pen (and sometimes graver corruptions), where possible by comparison with other, putatively if not actually, more reliable copies (emendare); by dividing words and punctuating (distinguere); and … by equipping his text with critical signs (adnotare).”4

Marginal Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC notes marked by an obelus (÷), an asterisk (*), or a dagger († and ‡) were used by scribes to identify suspicious passages and helped critics call attention to potential alternate readings instead of simply correcting or writing over the text.5 Ancient scholars like Galen (123 AD–c.200 AD) were often reluctant to alter a text with a correction, preferring simply to mark it and signal the need to go back to earlier texts for reference. This was particularly true when it came to editing the Old and New Testaments, as questions regarding who had the right to emend sacred texts became crucial. The existence of several competing Greek translations for the Old Testament naturally resulted in discrepancies that were often difficult to correct, as few scholars had enough knowledge of Hebrew to ascertain minute differences in the original texts. In addition, corrections needed to be done carefully so as to not disturb accepted readings and practices that had become the foundation of religious devotion.6 The study of errors and differences in the transmission of Biblical texts (and the inevitable controversies around this topic) in many ways gave rise to paleography—the study of writing traditions and dating of historical documents by discerning differences in handwriting.7

From the perspective of critical scholarship, the study of emendations and errors in ancient texts and textual transmissions has a long history. Aristarchus (c. 301–c. 230 BC) and Galen were among the more remarkable editors of early antiquity who practiced collation Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC and correction by comparing manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC sources, and sought to eliminate common scribal errors such as confusions between shapes and letters, skipped words, or missing lines. Later, early modern critics such as Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457), Poliziano (1454–1494), and Joseph Scaliger (1540–1609), have been credited as some of the first textual philologists of classical literature. For these critics and their successors, the question of how to identify errors became a crucial part of building an authentic and reliable history of ancient literature.8

Throughout the manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC period, books were produced through a variety of methods: authors might compose and prepare their own copy or employ a scribe to either take dictation or to copy from a final draft; libraries and monasteries used scribes to reproduce manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC for preservation and transmission; and universities similarly employed scribes to copy and distribute an approved copy of required texts (a tradition known as the “pecia system”). Scribes were thus crucial figures in the labor of textual transmission. The practice Harold Love has termed “scribal publication” effectively enhanced and expanded the circulation of texts among a more private and controlled network of readers both before and after the development of print.9 Scribes had systems in place for dictating and proofreading texts, usually involving aural as well as ocular revision: texts were often dictated to the scribe and then read back to check for errors.10

When copying the original manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC, scribes often acted as both editors and proofreaders. The correction process was recursive and continuous: corrections happened during the act of writing (drafting and revising to prepare a fair copy Fair Copy the final draft of a text (presumably free of errors) provided by the author to prepare a text for publication. CLOSE or ESC); in the process of copying texts (as the scribe might make conjectures about straightforward errors like misspellings); and after texts had been copied (wherein corrections might happen interlineally Interlinear written or printed between the normal lines of text. CLOSE or ESC or in the margins Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC).

Figure 1

Click For Larger Image

Caret mark, used to indicate passage or individual letters to be inserted in the text. CLOSE or ESC

An author’s manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC might go over multiple drafts in order to create a “fair copy Fair Copy the final draft of a text (presumably free of errors) provided by the author to prepare a text for publication. CLOSE or ESC” that would be ready for scribal publication. In order to make revisions clear and separate them from the text, the author or the scribe might indicate with a caret mark what words or lines needed to be inserted (see figure 1). The caret mark is still used in modern copyediting, as are many other types of scribal shorthand like brackets to add spaces between words or subpuncting to indicate words to be deleted.11

Figure 2

Click For Larger Image

Harley MS 1280, f. 313v. See on top right insertions made via Signe de Renvoi. Image courtesy of The British Library's Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.CLOSE or ESC

Corrections could be made by the scribe, by another hired scribe, or an official corrector at the scriptorium. Lines could be silently rearranged or edited at the scribe or corrector’s own discretion depending on the size of the page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC or what they perceived as errors in the manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC copy.12 Because several scribes were often responsible for copying the same text, a comparison of even a single copy against an authorial manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC (where those have survived and have been positively identified) can show discrepancies and errors such as a skipped word or line. Errors by omission were indicated by the use of a signe de renvoi (signal of return), with the text to be inserted added in the margins Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC (see figure 2). When it came to errors by addition—misspellings, repeated words or letters—scribes, correctors or, in the case of early drafts, authors themselves, could erase individual letters by using a scraping knife or pumice and manually inserting character Character any single meaningful mark that occurs in graphological communication; any single letter, punctuation mark, or special mark such as an asterisk, ampersand or question mark is a character, regardless of whether it is written by hand, printed, or manifested on a computer screen. See: Glyph CLOSE or ESCs where needed.

Scribal errors were common enough; in transmitting words from one manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC to another, a scribe might mistake a letter for another, miss a catchword Catchword a word printed in the lower right of the last page of a section. It is the first word of the next section and is used to assemble the sections in the correct order. Frequently, catchwords will appear on each page, as a means of ensuring, in the proofing stage, that all type pages have been imposed in the correct orientation in the forme. The line on the page in which the catchword appears is called the direction line. See: Collate CLOSE or ESC at the end of the line, or skip over a line entirely. Nonetheless, scribes also made thoughtful and detailed corrections, acting as both editors and critics. As we have seen above, scribal interventions by means of corrections represent some of the earliest evidence of textual reception and even, as Daniel Wakelin has recently detailed, literary criticism.13 Beyond his duty to mechanically transmit words from one page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC to another, a particularly dedicated scribe would strive to make corrections with an eye to honing his craft as well as preserving the work’s textual integrity.

In manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC and paleography studies, corrections help with dating and with ascertaining the transmission history of texts.14 Critics such as Eugene Vinaver, Anthony Grafton, Bernhard Bischoff, and Orietta Da Rold, among others, have chosen to study and identify a wide and distinct variety of scribal corrections and their ties to manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC transmission. These may include elements such as “units of errors: spelling changes, whole-word changes, and suspensions,” timely corrections (“simultaneously with the copying process” or after the book had been copied), and finally unintentional errors such as “‘miscounts, rewriting of Roman numerals, [or] wrong pronoun numbers.’”15

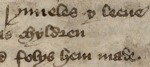

Figure 3

Click For Larger Image

William Langland, Piers Plowman (written c. 1370-90), f113r. Image courtesy of The Piers Plowman Electronic Archive.CLOSE or ESC

By collating Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC surviving copies, critics are able to use scribal corrections to investigate the degree to which the scribe(s) intervened in and altered textual meaning. The study of errors, as well as variants Variant a manuscript or printed text that contains textual variations (such as different words or spelling) from another known copy; can also refer to the textual variation itself. See: State CLOSE or ESC across copies of manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC, allows for contemporary scholars to reconstruct an “authoritative text” or to trace corrections back to a long-lost original. Such is the case for Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: each manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC organized the tales in a different order, and entire sections had been added or removed.16 Another famous example is the manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC of Piers Plowman, which bear correction marks in nearly every page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC, sometimes in three different hands (see figure 3). These manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESCs have provided fodder for much critical contention about the role of corrections in the search for an authoritative text.17 Even a scribe’s methods for self-correction can be of particular critical interest, as they reveal details about the scribe’s education, their tendency toward particular errors (such as confusion of letters like m and n), and common errors they consistently looked for. By identifying types of corrections such as striking out and rewriting, superscript writing, or conversion of one letter to another, a textual critic can become intimately familiar with individual scribes, which in turn helps identify future manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC copied by that same person.18 More recently, critics like Roger Chartier, Margaret Ezell, and David McKitterick have aimed to steer away from authorial intention and the dream of a perfect copy, focusing instead on what D. F. McKenzie famously termed the “sociology of texts.” This argument suggests that the text’s entire history, including its many errors, corrections, and new errors made in the process, is uniquely valuable for understanding the “social, economic, and political motivations of publishing.”19

Corrections in Print

The invention of the hand-press in the fifteenth century demanded that editors and printers develop new protocols for error correction. Following what Elizabeth Eisenstein identifies as “the printing revolution,” textual corrections could occur through amendments, stop-prints, proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC-corrections, cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESC page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs, and errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC.20 As in the case of manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC, corrections occurred during the process of preparing a text for print (by authors, printers, and compositors Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC), during the print-run (by printers, the author, or a professional corrector), after the edition had been completed (via errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESCs, stamping Stamping the practice of using an inked stamp to transfer text onto a page, typically after it had been through the press. Stamping could also be used to add borders, signatures, or catchwords. See: catchwords. CLOSE or ESC in new words or letters, or pasting over the text), and even beyond publication in the hands of zealous readers.

Authors were responsible for sending clear, “fair” copies of their work to the printer ideally as close to error-free as possible. Nonetheless, this did not always take place: printers’ notes in errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC frequently blamed poorly written copies for errors in the edition, as typesetters Typesetter the person responsible for manually placing pieces of type on a forme line by line to prepare the text for print. See: Forme Type CLOSE or ESC had a difficult time making out garbled hands or corrections subscripted over the text.21 Even when an author employed a professional scribe to produce a fair copy Fair Copy the final draft of a text (presumably free of errors) provided by the author to prepare a text for publication. CLOSE or ESC, such transcriptions likewise offered the possibility of new errors being introduced.

Once in the printing house, manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC were typically read over and corrected prior to typesetting and printing. The compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC, responsible for setting the manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC in type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC, was expected to not only carefully avoid potential omissions or additions but also make small corrections where necessary. Yet this process also introduced new errors, such as mismatched catchwords Catchword a word printed in the lower right of the last page of a section. It is the first word of the next section and is used to assemble the sections in the correct order. Frequently, catchwords will appear on each page, as a means of ensuring, in the proofing stage, that all type pages have been imposed in the correct orientation in the forme. The line on the page in which the catchword appears is called the direction line. See: Collate CLOSE or ESC, skipped lines, or “foul case Foul Case a type case containing one or more letter types accidentally placed in the wrong letter box. See: Type Type Case CLOSE or ESC” errors, which occurred when a piece of type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC had been accidentally placed in the wrong letter box. Once again, these surviving traces of errors, in addition to compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESCs’ idiosyncratic spelling choices, have proven extremely helpful for modern critics. Charlton Hinman’s highly detailed collation Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC of fifty-five copies of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s collected works helped show that five compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESCs had worked on producing the edition (broadly referred to as Compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESCs A, B, C, D, and E). Scholars such as T. H. Howard-Hill, Gary Taylor, and Paul Werstine built on Hinman’s work by singling out which compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESCs worked on which parts of the collection and even identified four new compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESCs—F (Howard-Hill) and H, I, and J (Taylor).22 Their often-unique errors and type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC choices allow scholars to identify (to varying degrees of certainty) from what copies each compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC may have worked.

As Anthony Grafton notes, corrections in the hand-press period were always discontinuous. Unlike in modern publishing houses, which typically print an entire copy of a text to be reviewed for corrections, early modern proofs Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC happened at the start as well as throughout an edition’s run. After some of the text had been set in type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC, the printer would produce a forme Forme the page or pages of type locked into position in a chase and ready for printing. This term can also refer to the printed matter that results from the impression of a single forme, i.e., one side of a printed sheet. See: Stereotype Electrotype Typesetter CLOSE or ESC (one side of a sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESC with a group of page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs) to be given to the corrector and the author to look over. This work, whenever possible, was done at the printing house or close by, although authors sometimes were sent proofs Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC and took a long time to return their corrections, potentially delaying the printing process (see “Spotlight,” below). Professional correctors, especially in continental printing houses, were employed to go over proofs Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC as copyeditor Copyeditor the person who is responsible for reviewing proofs and making corrections. See: Proof CLOSE or ESCs, fixing issues of punctuation and spelling. This work was expensive, however, and more likely to be called upon when the printer and compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC were unfamiliar with languages or styles used in a specialized text. Not unlike the manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC correctors and scribes who came before them, these correctors saw their labor as “both mechanical and intellectual”: correctors could be called upon to create indexes, look over graphic design choices, and work with authors on issues of content and meaning.23 In smaller printing houses, the corrector would typically be a master or senior journeyman, who would take over for the compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC to check the proofs Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC for errors (as the compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC was likely to overlook errors that might take long to correct). In collaboration with a “reading boy,” who typically read from the manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC out loud (with special inflections for punctuation), the corrector would then check the proofs Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC against the compositor’s copy.

The printer would then perform a “stop-press Stop-Press common abbreviation for a stop-press correction inserted at the last minute while the text is being printed. This often results in variant copies, where some might contain errors and others have been corrected. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESC” correction, stopping the printing to make corrections on the forme Forme the page or pages of type locked into position in a chase and ready for printing. This term can also refer to the printed matter that results from the impression of a single forme, i.e., one side of a printed sheet. See: Stereotype Electrotype Typesetter CLOSE or ESC and if necessary send the corrections back to the compositor Compositor the person responsible for arranging the type in the proper order so that it can be printed. CLOSE or ESC for resetting the type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC before continuing the print run Print Run the number of copies produced in a single edition or issue. See: Stop-Press Cancel CLOSE or ESC. Much of this process happened continuously throughout the run, however, as new errors were found and new corrections introduced. This effectively ensured that even in the run of a single edition few copies would be identical to one another.

Elizabeth Eisenstein suggests that this reproduction of errors was uniquely important for scholarly debate since manuscripts Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC did not allow for larger-scale comparisons and discussion at the level that print could. The mass-production of the printing press ensured that the errors present in a first edition (especially of classical texts for which, as we have seen, there was a growing body of scholarship) could help create what she terms “‘textus receptus’—a text that provided a common base for later disputes among scholars.” Because scholars could collectively access (more or less) the same copy of the text, “the persistence of learned quarrels over each edition had the additional benefit of stimulation of fresh findings bearing on classical studies and natural history.”24 As we will see below, this kind of community-driven correction is, in many ways, echoed in the types of collaborative editing scholars and readers perform on online texts.

Figure 4

Click For Larger Image

John 6:67, Geneva Bible (London: 1610), STC 2212. Image courtesy of Trevor Bond/WSU Libraries and The Collation.CLOSE or ESC

After the print run Print Run the number of copies produced in a single edition or issue. See: Stop-Press Cancel CLOSE or ESC was completed, any remaining errors could be corrected by cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESC-leaves Leaf the sheet of paper or parchment with one page on its front side (recto) and another on its back (verso). See: Recto Verso Page Codex CLOSE or ESC (typical) or cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESC-sheets Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESC (less common): the original leaf Leaf the sheet of paper or parchment with one page on its front side (recto) and another on its back (verso). See: Recto Verso Page Codex CLOSE or ESC or sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESC would be destroyed and a corrected version would be typeset and either substituted by breaking up the binding Binding Edge the bound edge of a book. See: Back Back Margins Codex CLOSE or ESC (in the case of cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESC-sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESCs) or pasted over a page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC on the book to replace it (cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESC-leaf Leaf the sheet of paper or parchment with one page on its front side (recto) and another on its back (verso). See: Recto Verso Page Codex CLOSE or ESC). A trimmed slip could also be pasted to replace a single word or line, as in the infamous case of the 1610 Geneva Bible, in which a passage meant to quote Jesus said “Judas” instead25 (see figure 4).

We may note at this point that all the examples have so far addressed the correction of errors caught during the process of preparing the text for (scribal or print) publication. The idea of generating a list of errors to be corrected post-publication (errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC) seems to have been a product of the printing house. The first known errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESC appeared in Juvenal (Venice 1478), potentially signifying the expectation that readers might play a larger role in the lifecycle of printed books.26

Errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESCs, as Seth Lerer has argued, are a rich “place holder in the ongoing narratives of bookmaking and book reading”—acting as both a product of their immediate moment and a reminder of readers’ role in correcting and responding to the book in front of them.27 Errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC might precede invitations for the reader to act as editor, not simply correcting errors found by the printer but also undertaking the task of locating uncatalogued mistakes. Although there is evidence that many readers did indeed follow the instructions in errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC lists, Henry S. Bennett suggests that the majority never “persevered beyond the first fifty or sixty pages Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC.”28 Readers could (and often did) resist printed instructions, but they also corrected books to fit their own needs, manually adding folio Folio a sheet of paper folded in half to make two leaves / four pages. Can also refer to the leaf number of a foliated book. See: Format CLOSE or ESC numbers to a provided table of contents, for example, or making notes next to passages they intended to copy.29

Playful notes on errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESCs may have offered attentive readers a reward for locating errors. For example, in The King of Utopia his Letter to the Citizens of Cosmopolis (1647), an anonymous author uses the idea of textual corrections as a political argument:

page 103. Line 50. For a good thing read a true subject. Page 883. Line 75. For Tyranny, read Taxations. Page 68. Line 15 for Burglary read Plunder, Page 94. Line 101. For Common-wealth read Committee. Page 115 for Service read Sacriledge. Page 40. line 100. For Bishop read Presbyter. Page 56 line 80 for Pulpit read Tub. Page 37. Line 64 for Preaching read Prating.30

Here the author equates textual correction with the correction of ideological mistakes, reminding readers that “tyranny,” for instance, should be more accurately defined as “taxations” which were unfairly placed on the populace. The errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC list similarly criticizes errors in assuming that bishops (and the pulpit from which they preached) were doing anything but “prating.” These intentionally fake errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC lists suggest that even if readers did not bother with corrections, they did at least read through the list of errors. In this case, the author equates textual corrections with political subversion—by intervening in the text, the reader might, in theory, be setting the country right.31

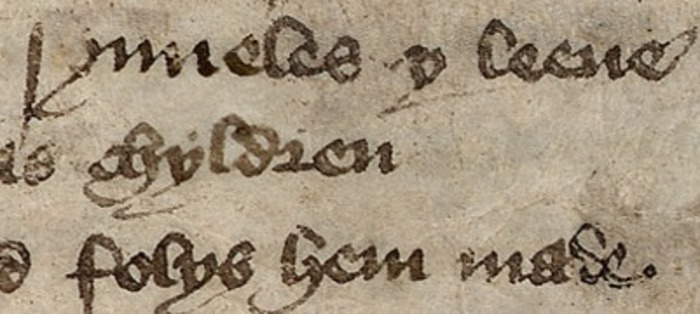

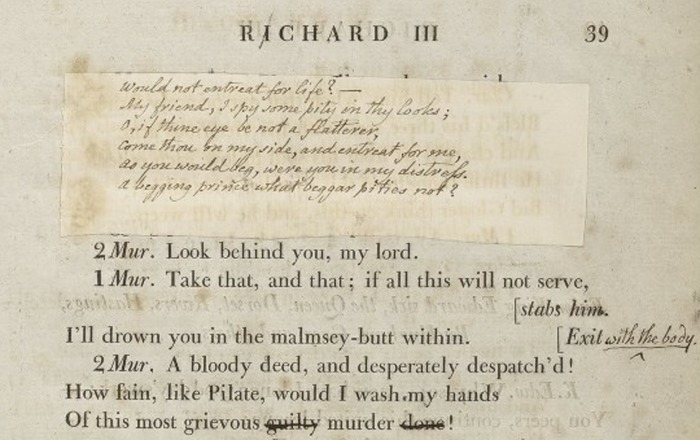

Figure 5

Click For Larger Image

William Shakespeare, Richard III (London: 1791). Image courtesy of Folger Shakespeare Library.CLOSE or ESC

Corrections to printed texts are not necessarily synonymous with error—there is evidence that publishers, editors, and even theater directors used existing printed editions as a basis for new editions, marking the text for necessary changes32 (see figure 5). As Stephen Dobranski argues, the act of finding and correcting errors connected readers, authors, and printers in a “shared authority”; readers in particular “could still approach both printed and manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC works as something not entirely complete, on which they could—and were encouraged to—collaborate.”33 Unfortunately, such collaboration was relegated almost exclusively to male readers, as women were far less likely to annotate and mark books.34

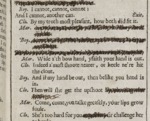

Figure 6

Click For Larger Image

William Shakespeare, Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (London: 1632). A copy censored thanks to the Spanish Inquisition. Image courtesy of The Folger Shakespeare Library.CLOSE or ESC

At the margins of what we might formally call a textual correction, the early modern period also produced some of the earliest evidence of “institutionalized press corrections” that were, arguably, a call for censorship. In response to Archbishop Niccolo Perrotti’s request for accurate corrections of highly specialized books, the Council of Trent (1545) was charged with putting together an ever-growing list of works considered offensive to Catholic devotional practices. The list would later split into two parts: the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which listed books and authors to be banned from circulation, and the Index Librorum Expurgatorius, which catalogued books that could eventually be sold and printed following extensive correction.35 In the late sixteenth century, the Pope employed both scholars and laymen to go over the list of corrections and help place the ever-growing number of books on the Index Expurgatorius back into circulation. According to Ugo Rozzo, however, some correctors were reticent to alter or disrupt texts they admired, while others simply felt that by the time the books were back in circulation they would no longer have a market of readers, making the corrections ultimately pointless.36 As a result, works were often held in a suspended state away from the public for long periods of time. Even when books were allowed through such strict censorship, there is evidence that devout readers or publishers could take it upon themselves to correct or redact publications they found to be offensive whether or not they were included in the Index. Although from a bibliographical perspective these redactions may not constitute a textual correction (because they deal in ideological disputes over content, rather than the type-setting and clarity of the text itself), it is clear that the line between control, correction, and censorship was and continues to be a tenuous one (see figure 6).

By the nineteenth century, the invention of the steam-powered press in 1814 and, later, the rotary press in 1843 helped stabilize and accelerate the printing process. Texts printed in this period did not necessarily contain fewer errors, but those errors could be much more quickly corrected with minimal disruption to the print run Print Run the number of copies produced in a single edition or issue. See: Stop-Press Cancel CLOSE or ESC. The development of monotype Monotype a twentieth-century machine used to produce metal types used for relief printing. See: Linotype CLOSE or ESC and linotype Linotype a machine that casts a line of hot-metal type used primarily to print newspapers. See: Monotype CLOSE or ESC machines in the late nineteenth century introduced a mechanized process for setting type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC. This process made error correction faster— especially in the case of monotype Monotype a twentieth-century machine used to produce metal types used for relief printing. See: Linotype CLOSE or ESC, where a single letter could be replaced without ruining the entire cast row. Stereotyping Stereotype a common method of printing in the 19th century where molds, made from complete formes of type, were used to re-print a work without having to set the type again. See: Forme CLOSE or ESC (1811) and electrotyping Electrotype a process by which a plate for printing in relief is created by coating a forme with a conductive material and adding copper or nickel to the surface. See: Forme CLOSE or ESC (1841) eventually allowed for a metal plate Plate the surface, usually metal, that carries an image to be printed. CLOSE or ESC to be produced from a previously set type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC, which reduced the number of errors introduced by resetting type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC for new editions.

The most significant change during the nineteenth-century is perhaps the professional proofreader: an in-house worker charged with checking proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCs against the set type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC and the provided manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC in order to identify and correct errors. This was especially the case for newspaper presses and burgeoning university presses, although proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCs were still sent to the author for correction as well. After the text had been set, lines of type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC would be moved to the galley Galley a wood or metal tray with one or two open sides used to gather composed lines of type. See: Type CLOSE or ESC, a long metal tray capable of holding large amounts of text. Depending on the size of the work and the amount of corrections the printers anticipated, the printer might pull galley Galley a wood or metal tray with one or two open sides used to gather composed lines of type. See: Type CLOSE or ESC-proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCs for review before the matter was made into page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs. A galley Galley a wood or metal tray with one or two open sides used to gather composed lines of type. See: Type CLOSE or ESC-proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESC or “slip” was typically a long strip of text to be sent for the author’s review.37 For smaller jobs, however, the practice of imposing the text onto page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs and making up page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCs was still common.38

After the metal plate Plate the surface, usually metal, that carries an image to be printed. CLOSE or ESC had been created from the set type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC, corrections could be made by cutting or punching out the mistake and soldering in corrected pieces of type Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC (“botching”) or soldering in corrected pieces of a plate Plate the surface, usually metal, that carries an image to be printed. CLOSE or ESC (“mends”). This could be a painstaking process that involved carefully chiseling out the correct size for the new insertion or drilling a hole where the plate Plate the surface, usually metal, that carries an image to be printed. CLOSE or ESC was to be mended.39 In possession of a fully-corrected plate Plate the surface, usually metal, that carries an image to be printed. CLOSE or ESC, however, a printer could make several reprints and reuse the same plate Plate the surface, usually metal, that carries an image to be printed. CLOSE or ESCs for many years to come. This process, then, helped ensure that new errors were less likely to be introduced in the process of preparing reprints.

The study of errors, corrections, and textual transmission practices in nineteenth-century texts has been the focus of scholars such as Fredson Bowers, G. Thomas Tanselle, and Peter Shillingsburg. Much of this discussion has surrounded the role of the editor and the “ideal copy,” particularly in regard to what W. W. Greg termed “accidentals Accidentals term used by W. W. Greg to define errors that do not typically affect author\'s meaning, such as spelling variation and punctuation errors. CLOSE or ESC” and the material history of printed books. Tanselle, for example, differentiates between the role of the editor and the bibliographer. According to him, the editor may wish to put together an edition that offers a textual reconstruction, using several copies in order to achieve the best possible version of a given text—a version which, regardless of its history of corrections, represents both the author’s intentions and the print shop’s final version. The bibliographer, however, should be generally concerned with studying the text as physical object, considering its diverse “states State variation among copies of the same edition, typically due to the correction or reintroduction of errors. See: Variant CLOSE or ESC”—issues of the same edition that contain variations due to corrections or overlooked errors. In this sense, whereas a critical edition may concern itself with the careful process of selecting corrected states State variation among copies of the same edition, typically due to the correction or reintroduction of errors. See: Variant CLOSE or ESC from various copies to produce the “best” overall text, the “ideal copy” may itself be an abstraction, as it seeks to describe the ideal state State variation among copies of the same edition, typically due to the correction or reintroduction of errors. See: Variant CLOSE or ESC of the book that “encompasses all states State variation among copies of the same edition, typically due to the correction or reintroduction of errors. See: Variant CLOSE or ESC of an impression or issue.”40 Building on this, Shillingsburg suggests that the advent of computer-assisted editing and hypertext Hypertext any system which allows the connection and navigation of computer documents through links. CLOSE or ESC editions should allow editors to think about variants Variant a manuscript or printed text that contains textual variations (such as different words or spelling) from another known copy; can also refer to the textual variation itself. See: State CLOSE or ESC and corrections as part of an edition’s history. In other words, creating the “best” possible edition risks robbing readers of the rich history of texts and should thus be considered more carefully.41

Corrections in the Digital Age

The advent of the internet and the development of the personal computer have brought along new kinds of errors and new approaches to correction. We may find digital corrections in the form of “dynamic content Dynamic Content web content that is subject to change over time. CLOSE or ESC” (ever-changing and always subject to alteration), or even as crowd-sourcing and open peer-editing. Electronic composition and correction are of course not immune to the problems of transmission identified above. The automated process has in some cases replaced human-eye transcription and facilitated approaches to collation Collate to gather sheets or gatherings so that the pages are in proper sequence. Hence, the collation formula, which is a bibliographic description of the gatherings and the order in which they are gathered. This term is also used in the sense of a close comparison between two similar or ostensibly identical copies with the goal of identifying differences between copies. See: Signature Catchword CLOSE or ESC and proofreading, but it is likewise prone to error. Indeed, the problem of horizontal transmission and contamination persists, as editors use previous texts from other publishers to create their copy and, in the process, accidentally reproduce old errors and introduce new ones. For example, the 1981 Penguin edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin derives from an earlier Harvard edition (1962) which, itself, is based on the 1852 Jewett edition. In preparing their edition without returning to the 1852 copy, the Penguin editors inherited errors from the Harvard edition and, in the process, introduced further errors. Many of these were then compounded by Optical Character Recognition (OCR) issues when the edition was later digitized.42

The benefits of digital editing and publishing, however, cannot be overstated. Thanks to modern technology, scholars have managed to not only transcribe and digitize (and therefore preserve) rare books but also to make them available to an unprecedented audience online. These transcriptions often involved (and many continue to involve) careful, manual work. While we may expect the human eye to be more naturally prone to error, computational technologies like OCR come with their own set of issues. Particularly in the case of pre-nineteenth-century texts, the OCR reader often confuses the long S character Character any single meaningful mark that occurs in graphological communication; any single letter, punctuation mark, or special mark such as an asterisk, ampersand or question mark is a character, regardless of whether it is written by hand, printed, or manifested on a computer screen. See: Glyph CLOSE or ESC for the letter F, misinterprets catchword Catchword a word printed in the lower right of the last page of a section. It is the first word of the next section and is used to assemble the sections in the correct order. Frequently, catchwords will appear on each page, as a means of ensuring, in the proofing stage, that all type pages have been imposed in the correct orientation in the forme. The line on the page in which the catchword appears is called the direction line. See: Collate CLOSE or ESCs at the bottom of page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs, and often cannot recognize simple differences like distinguishing between the letter “m” and “rn” (e.g. “um” vs. “urn”). These confusions may perhaps recall the work of scribes and the problem with inconsistent handwriting or jumbled letters. Unlike the practices honed by print culture, however, the process of proofreading and correcting OCR has yet to be regularized. Projects such as Early English Books Online’s Text Creation Partnership have worked on double-keyed transcriptions followed by additional (human) proofreading, while the ongoing Early Modern OCR Project (EMOP) has been teaching their machines to recognize early typeface Typeface a particular design of type. See: Face Type x-height Ascenders CLOSE or ESCs and other idiosyncrasies of the period, implementing corrections to the code along the way.43

Thanks to OCR and other digitizing techniques, websites such as the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) have provided readers with thousands of copyright-free, open-access texts. For the sake of speed and cost, however, the majority of these texts were published as is—with minimal to no correction or proofing. Diana Kichuk asks: “is accuracy no longer a major reader expectation?”44 If the hundreds of readers who visit Project Gutenberg daily are any evidence, perhaps the answer is “no.” At best, the average reader may be willing to overlook errors in favor of a good argument or entertainment value.45 As Kichuk demonstrates, however, plenty of e-texts have such a high frequency of errors as to make them nearly unintelligible. Thankfully, the digital age allows for ongoing (and often not cost-prohibitive) corrections and quality-control. Websites like Project Gutenberg, academic repositories like 18thConnect, and newspaper archives around the world have come to rely on anonymous crowdsourcing as well as individually-identified contributors for mass-scale corrections. Gutenberg’s own Distributed Proofreaders benefits from thousands of volunteer members and has proofread over 30,000 books.46

If the printing press helped usher in new kinds of systematic corrections, digital technologies have similarly brought about the need for medium-specific corrections, such as addressing errors in metadata Metadata descriptive information about a given document, such as place of publication, author, imprint. See: CLOSE or ESC. Metadata Metadata descriptive information about a given document, such as place of publication, author, imprint. See: CLOSE or ESC refers to the descriptive information which allows search engines and websites to encode and catalogue front-end data. If the metadata Metadata descriptive information about a given document, such as place of publication, author, imprint. See: CLOSE or ESC on a given book is incorrect, that book may not come up on a targeted search or may be incorrectly catalogued by the system. Such corrections can only be performed on the back end of the website, typically by its developers. OCR and other digitized methods of textual transcription and data gathering also allow for a wholly different type of correction: the modernization of spelling. Editors working on materials printed before English spelling was formally standardized in the eighteenth-century sometimes choose to modernize titles as well as names of printers, publishers, and other collaborators. While not formally a correction in the sense we have discussed so far, these alterations can, in theory, facilitate the inclusion of variants Variant a manuscript or printed text that contains textual variations (such as different words or spelling) from another known copy; can also refer to the textual variation itself. See: State CLOSE or ESC in search engines. Yet, many researchers find that such editorial choices are misleading.47 A scholar attempting to understand textual variation and spelling choices might be unable to perform accurate research due to such modernizations. Worse yet, because these modifications are often not done transparently, for many digital repositories it would be difficult or impossible to know how the search results have been impacted by modernized metadata Metadata descriptive information about a given document, such as place of publication, author, imprint. See: CLOSE or ESC.

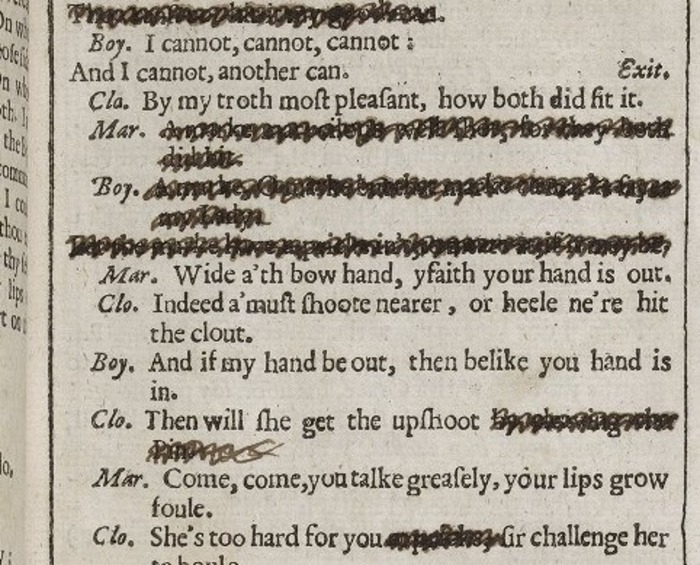

Figure 7

Click For Larger Image

Production Drawing (October 2013; March 2015). Full text available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Production_drawing. CLOSE or ESC

Wikipedia is arguably the best modern example of the power corrections have to influence readership and reception. Thriving on user input to create, edit, and amend its entries, Wikipedia once had a reputation as an unreliable and untrustworthy source. For example, in 2006 several United States Congress staff members were accused of editing page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs for politicians such as Marty Meehan and Joe Biden to remove undesirable facts.48 But Wikipedia corrections have also helped expose deeply problematic issues within the study of the literary canon. In 2013, a Wayne State University graduate student in history, John Pack Lambert, began systematically removing women writers from the “American Novelists” category and placing them in the “American Woman Novelists” category he had newly created. The change (to call them “corrections” might qualify as a political move of its own) caught the attention of novelist Amanda Fillipacchi and soon sparked a larger debate among Wikipedia editors on the validity of Lambert’s (arguably sexist) editorial choices.49 Although a critical scholar might accurately perceive these changes as deeply ideological and therefore not technically “corrections,” Lambert claimed his goal was to facilitate searching at the granular level of metadata Metadata descriptive information about a given document, such as place of publication, author, imprint. See: CLOSE or ESC—by making a distinction between “women novelists” and “American novelists,” he intended to correct ambiguities in the search engine. Of course, his work was arguably motivated by larger and more problematic distinctions between what counts as traditional canonic literature. Much like our example regarding the Council of Trent, this demonstrates that the notion of “correction” may be used as a smoke screen to disavow certain kinds of ideological changes at the level of textual content. Despite these issues, Wikipedia is nonetheless an interesting model for transparency in the correction process: at the same rate as erroneous information might be created, it can just as quickly be caught, discussed, and corrected—or at least marked for correction in anticipation of more knowledgeable editors (see figure 7).

With the advent of the internet and social media, texts and ideas are markedly unfinished, open to interpretation, and subject to correction. Although some may argue that this has made the twenty-first century an age of unstable, unreliable information, as we have seen in this historical overview, readers have always perceived texts as open to corrections and revisions in one way or another.

A Discovery of Errors (1622) and the Correction Feuds between Brooke, Vincent, and Jaggard

As has been demonstrated throughout this overview, errors are inevitable to and inextricable from the cycle of textual production and reproduction. Yet being error-prone or insensitive to the process of correction could tarnish a printer’s reputation. Or at least that is what William Jaggard, the printer famous for Shakespeare’s First Folio, conveys in his preface to Augustine Vincent’s A Discovery of Errors in the First Edition of the Catalogue of Nobility (1622). Although A Discovery of Errors has become notorious as the publication that “interrupted” the printing of the First Folio, the work—as well as three publications by Ralph Brooke, with whom Vincent clearly had an ideological feud—offer a fascinating glimpse into how authors and printers reacted to accusations regarding uncorrected errors in print.50

The controversy dealt with the correct attribution of lineage and heraldry of English nobility, and seems to have been ignited by the publication of William Camden’s Brittania in 1577. Brooke was extremely vexed by the mistakes Camden had made in his historical account of the British nobility—perhaps he felt particularly offended that he had not been consulted for the publication, despite having (so he claims) fifty years’ experience as a herald. In response, Brooke took it upon himself to publish in 1594 A Discouerie of Certaine Errours Published in Print in the Much Commended Britannia. In it, Brooke claims he feels a duty to identify the errors in Camden’s work for the sake of defending their profession. The publication is set up dialogically with small segments from Brittania followed by two to three page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESCs in which Brooke attacks Camden personally. For example, in correcting a reference about Lord Berkley, he tells Camden: “in this title of Berkley, you make Morice the sonne of Robert Fitz-Harding to be sonne to his owne wife: which unnatural marriages, though well liked of by your selfe, yet never knowne nor allowed of by any others.”51

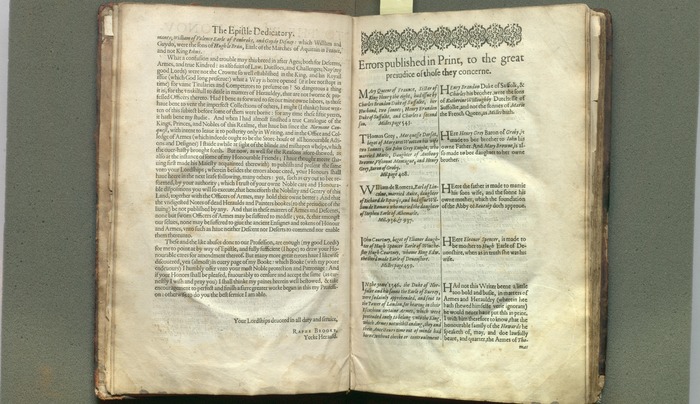

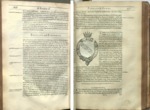

Figure 8

Click For Larger Image

Ralph Brooke, A Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, and Viscounts (London: 1619). Uncorrected version. For the cancel leaf printed to substitute missing text in this page, see Figure 11. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

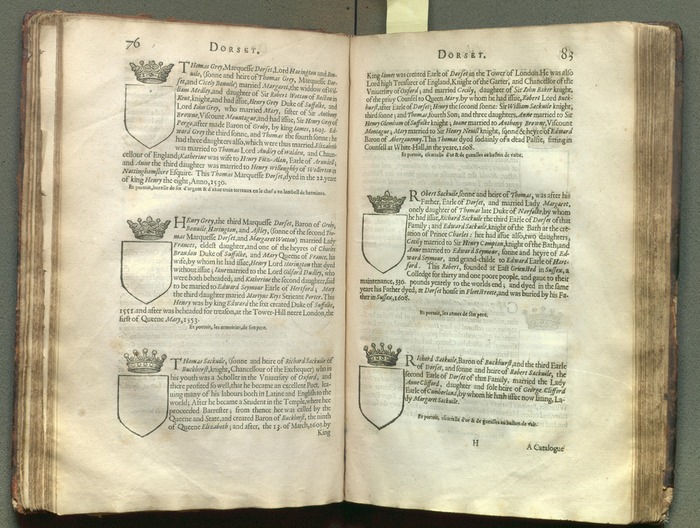

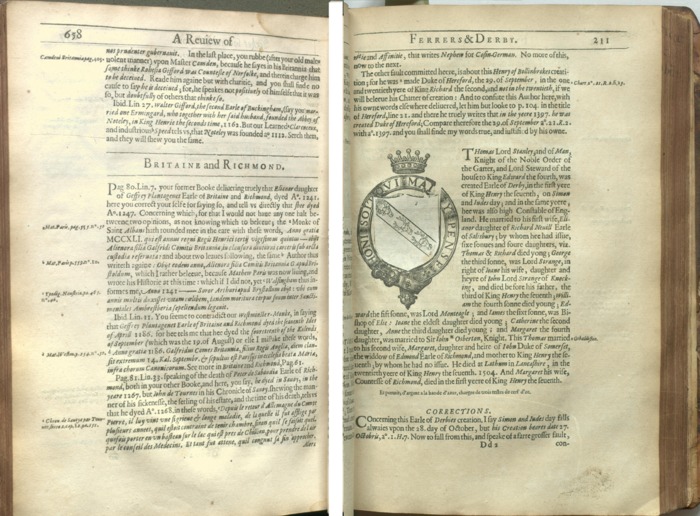

Figure 9

Click For Larger Image

Ralph Brooke, A Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, and Viscounts (London: 1619). Page 77 misnumbered as 83. This sheet has an additional error: a duke’s coronet is placed above Robert Sackville’s shield, rather than an earl’s. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

Twenty-five years later, Brooke published a heraldry book of his own, the Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, and Viscounts of this Realme of England, since the Norman Conquest, to this Present Yeare, printed by William Jaggard. In the preface to King James, he argues that his aim with the edition is to “discover and reforme many things heretofore grossley mistaken, and abused by ignorant persons who, venturing beyond their owne element and skill to write of this subject, have shewed themselves more bold and busie, then skillfull in Heraldry.”52 Yet Brooke himself later admits to the introduction of new errors, mainly in his list of “Notes of Dead Heralds” but also “many more great errors have I likewise discovered, yea (almost) in every page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC of my booke,” although he fails to specify what kinds of errors these might be.53 Preceding the errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC for this volume, Brooke offers a list of “errors published in print, to the great prejudice of those they concern” (see figure 8). Much like in his Discovery of Errors, the tone of Brooke’s corrections is derisive and snide, addressing even typographical errors such as a switch in numbers—which accidentally stated King John was born in 1227 and died in 1572—with a sarcastic remark that “surely I have not read of any so olde since Christs time.”54 Ironically, Brooke’s own edition was rife with pagination Pagination the numbering of pages. See: Foliation Page CLOSE or ESC issues and other more glaring errors, something the author seemed uneasy about admitting (see figure 9).

Having witnessed the level of scorn with which Brooke treated his fellow authors, Jaggard should not have been surprised to see his own reputation attacked in the second edition of the Catalogue and Succession, published in 1622 by William Stansby. In addition to a slightly revised dedication to King James, the edition includes a preface “To the Honourable and Judicious Reader.” Brooke announces that his second edition not only includes additional materials but also that he has corrected “many escapes, and mistakings, committed by the printer, whilst my sickness absented me from the presse, at the first publication” and which, according to him, have given his “envious detractors” cause for critique.55 Brooke preemptively responds to his future critics, stating that even should they find errors in his work (which any person inevitably will, as evidenced by the printed errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC list immediately below his preface), the reader should keep in mind “how much more painful it is, to compile a laborious Volume, then to carpe at it.”56 The irony of this statement seems lost on Brooke, who had already earned a reputation as overly critical and antagonistic.

Perhaps it was the large undertaking of the First Folio that fueled Jaggard to publicly defend this work? Had he heard from other printers about the new edition, or from his friend, the herald Augustine Vincent, who had been preparing his own Discovery of Errors as a response to Brooke? Whatever the reason, Jaggard stopped the work on the First Folio in order to publish, in 1622, A Discovery of Errors in the first Edition of the Catalogue of Nobility. Unlike Brooke, Vincent is straightforward in his goal, which is primarily to humble his colleague by giving him “a true glasse, wherein to see himself, that abandoning those multiplying glasses, which have made him believe, that he is so many times more then [sic] he is, he may see himselfe to be sicut unum e nobis, a man as we are, subject to ignorance and error.”57

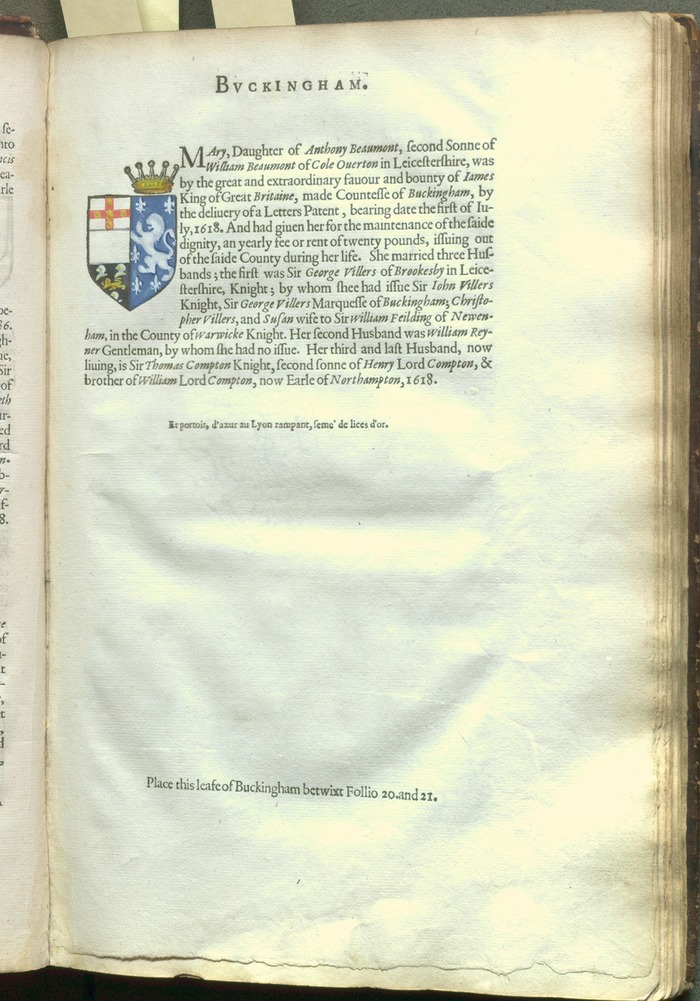

Figure 10

Click For Larger Image

Ralph Brooke, A Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, and Viscounts (London: 1619). Pasted leaf with instructions for the binder. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

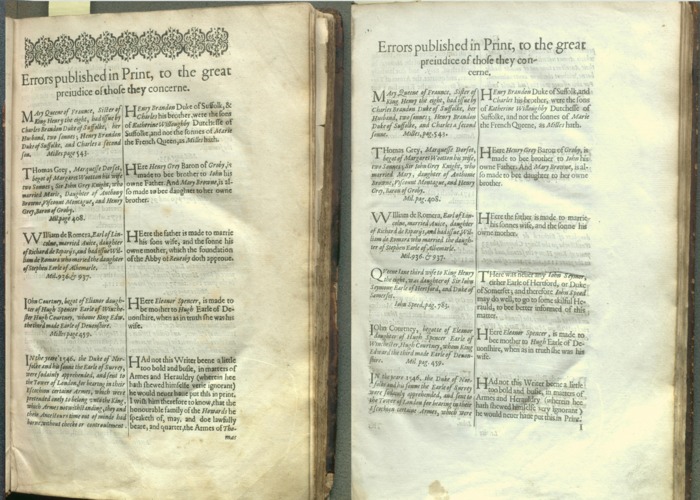

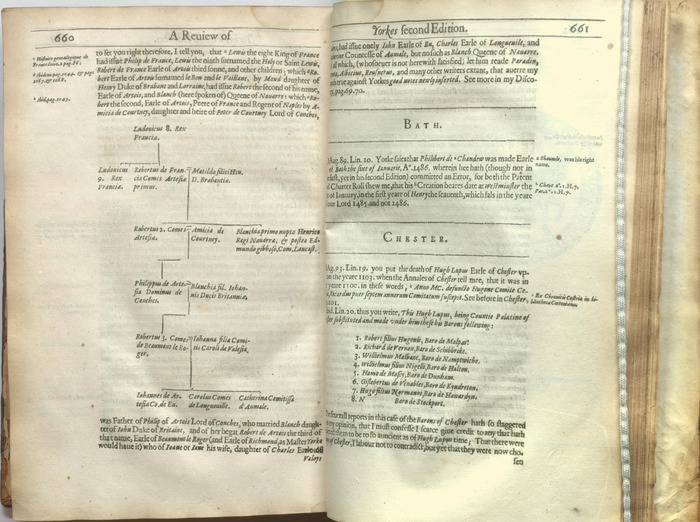

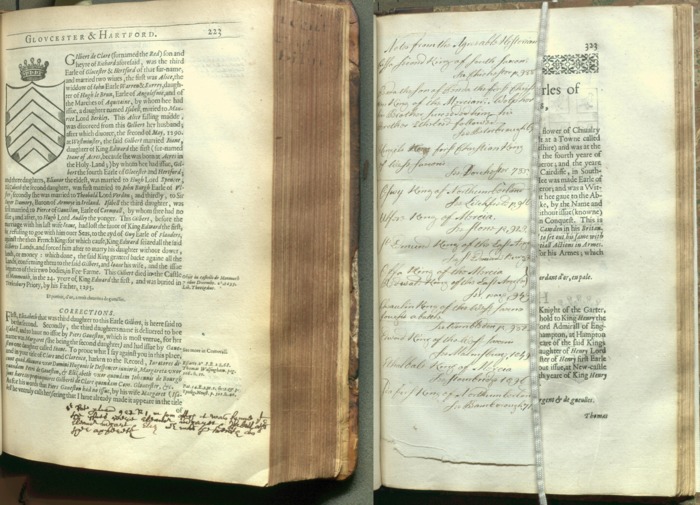

Figure 11

Click For Larger Image

Ralph Brooke, A Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earles, and Viscounts (London: 1619). Uncorrected leaf with missing text (left) next to inserted leaf cancel (right). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

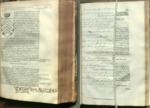

Figure 12

Click For Larger Image

Augustine Vincent, A Discouerie of Errours in the First Edition of the Catalogue of Nobility (London: 1622). Blank pasted-on slip (left) and new shield insertion with pasted-on slip (right). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 13

Click For Larger Image

Augustine Vincent, A Discouerie of Errours in the First Edition of the Catalogue of Nobility (London: 1622). Overprinting at the bottom of the page. Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

Jaggard’s preface, titled “The Printer,” responds directly to Brooke’s earlier allegations, claiming that Brooke was cowardly and dishonest in his preface to the second edition of the Catalogue. The printer accuses Brooke of having poached the (unpopular) edition from his shop, delivering it to another printer “when there lay yet (and yet do) of the former impression, almost two hundred of five, rotting by the walles.”58 Most importantly, however, Jaggard makes a point to distinguish between errors the printing house is likely to commit (and attempt to correct) and errors in the content, for which the author is solely responsible. The printer relies on his reader’s capacity to identify the typical (and forgivable) faults of the press, when not even “the meanest reader were like to stumble at such strawes, nor the most captious adversarie would go a hawking after syllables.” Incredulous at the very accusation that the press workers might deliberately introduce errors while Brooke was absent, Jaggard marvels at the extent to which the workmen would have to go for Brooke’s claims to prove true:

what time could it possibly bee, but in Master Yorkes absence from the presse, occasioned by his unfortunate sickness? Who all the time before, while hee stood sentinell at the presse, kept such strict and diligent guard there, as a letter could not passe out of his due ranke, but was instantly checked and reduced into order; but his sickness, confining him to his chamber, and absenting him from the Presse, then was the time, that the Printer tooke, to bring in that Troiane horse of barbarismes, and literall errours, which over-runne the whole volume of his Catalogue. Neither makes it to the purpose, that in the time of his vnhappy sicknesse, though hee came not in person to over-looke the Press, yet the Proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCe, and Reviewes duly attended him, and he perused them … I must confesse, that the sight alone of such a reuerend man in a Printing-house, like an old Fencer vpon a Stage, would do more good for keeping the presse in order, then the view, and review of twentie proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCes by himselfe with all his Latine, and other learning, he being in the meane time personally absent from the Presse.59

This rant is particularly illuminating, as it offers evidence that authors were often present at the printing house to look over the correction of errors and that, whenever necessary, proof Proof a trial print usually used for error-checking. See: Copyeditor CLOSE or ESCs might be sent to their home for proper revision. It further illustrates some key differences between errors that are natural to the hand-press process, including problems with spelling or grammar (“literal errors”) and what Jaggard terms “material faults,” which come down to the argument and message of the text. Indeed, Jaggard’s editions for both Vincent and Brooke feature a number of typical errors and corrections such as mislabeled pagination Pagination the numbering of pages. See: Foliation Page CLOSE or ESC, inserted leaf Leaf the sheet of paper or parchment with one page on its front side (recto) and another on its back (verso). See: Recto Verso Page Codex CLOSE or ESC cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESCs (see figures 10 and 11), pasted-on cancel Cancel a new leaf or sheet that has been printed to replace a section of the text containing errors caught while it was undergoing its print run. See: Print Run CLOSE or ESCs (see figure 12), and overprinting Overprinting a correction made to a text by running the sheet over through the press a second time and superimposing the correction or by hand-stamping a single letter over an already-printed one. See: CLOSE or ESC (putting the sheet Sheet a whole piece of paper. CLOSE or ESC through the press a second time to add in an omitted line)60 (see figure 13).

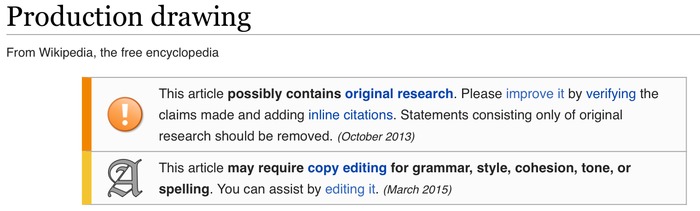

Figure 14

Click For Larger Image

Manuscript corrections of content issues in Vincent (left) and Brooke (right). Image courtesy of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library.CLOSE or ESC

The impact of error and correction in these publications is both literal and rhetorical: we may see clearly through Brooke’s (and Vincent’s) intentions to self-aggrandize in claiming to perform a public service of corrections. And yet, the fact that Brooke’s own printer felt he needed to formally join the controversy suggests that printing houses drew a very hard line between acceptable errors, for which they candidly asked the reader’s pardon and assistance (as Jaggard says in the errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC to this Discovery of Errors: “misconstruction afterwards is not more common, then slips are incident to books in the presse”) and errors of interpretation, for which the press should not be blamed or even be expected to intervene (see figure 14). Whereas scribes might often feel compelled to make interpretative and critical decisions in copying a manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC, this behavior suggests a change in perspectives: despite any potential errors and technical corrections, the press had to maintain a mostly dispassionate, mechanical approach—otherwise books might take years to finally be ready for the shop.

These examples demonstrate the degree to which errors and their corrections could become a contentious subject, representative not just of professional reputation and pride but, more broadly, of personal ideology. Further, even in their overzealous approach toward correction, Brooke and Vincent (and their printers, Jaggard and Stansby) could not prevent the introduction of new errors. Whereas it may be pointless to seek an error-free final copy, the errors and corrections that linger in written texts have provided (and will continue to provide) readers and scholars with a rich account of the structures, practices, and shortcomings of textual production, reproduction, and transmission as well as the efforts of scholarly editing in recovering or emending the many accidentals Accidentals term used by W. W. Greg to define errors that do not typically affect author\'s meaning, such as spelling variation and punctuation errors. CLOSE or ESC and intentions of authors, scribes, print workers, and digital editors alike.

Anderson, Nate. “Congressional Staffers Edit Boss's Bio on Wikipedia.” Ars Technica, January 30, 2006. Accessed 13 June 2015. http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20060130-6079.html.

Anon, The king of Vtopia his Letter to the Citizens of Cosmopolis, the Metropolitan City of Vtopia. Printed at Cosmopolis in the Year 7461 and Reprinted at London An: Dom 1647. Wing K575. Early English Books Online. Accessed 10 June 2015.

Beal, Peter and A. S. G. Edwards, Scribes and Transmission in English Manuscripts, 1400-1700. London: British Library, 2005.

Bennett, Henry S. Early English Books and Readers 1603 to 1640. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Bowers, Fredson. “Criteria for Classifying Hand-Printed Books as Issues and States.” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 41 (1947): 271-92.

Brewer, Charlotte. Editing Piers Plowman: The Evolution of the Text. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Brooke, Ralph. A Discouerie of Certaine Errours Published in Print in the Much Commended Britannia. London, 1594.