ArchBook: Architectures of the Book

Published 21 December 2016

Corrected and updated 10 February 2022

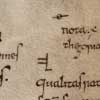

Figure 1

Click For Larger Image

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 352, fol. 3v (detail). Boethius, De institutione arithmetica, with marginal and interlinear glosses. Image courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.CLOSE or ESC

Signe-de-renvoi, meaning "sign of return," is a term for a visual mark, usually in a manuscript Manuscript any document in which the text is written by hand. See: Script CLOSE or ESC, that links a location in a text to a corresponding correction, annotation, or cross-reference in the margin Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC. The "return" refers to the reader's practice of leaving the primary text to read the annotation and then returning to the primary text. Signes-de-renvoi are sometimes referred to as tie marks or tie notes, although these are also (and perhaps better) used to refer to symbols that link textual elements on different pages Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC.1

Symbols used for signes-de-renvoi vary widely in form (see fig. 1). Crosses, patterns of dots, arrows, and combinations of dots and lines were common symbols used for signes-de-renvoi. A signe-de-renvoi is normally neither a number or a letter in the symbol set used for the primary text; in that sense it is distinct from the primary text, and it signals content that is also spatially separated from the main text block.

Signes-de-renvoi are primarily used to link corrections, commentary, annotations, and other marginal content to the main text, in what historians of print sometimes call a keying system.2 They should be differentiated from symbols used as finding or indexing aids, such as capitulum, paraph, or section marks that occur in the main text block or provide cues in the margin Margin white space surrounding the area taken up by printed matter. See: Back Margins Head Foot Manicule Marginalia CLOSE or ESC. These visual indexing strategies use fixed positions on the page to indicate textual structure and aid searches for particular content, whereas signes-de-renvoi are bi-directional linking devices, requiring the reader to leave and return to the main text, and thus guiding the reader from text to margin and back again. Signes-de-renvoi were used in production and correction of texts at all stages of the life of a manuscript to signal points of correction or add supplementary material. They save extensive corrections or annotations from becoming crowded and disorganized, enabling a simple process whereby the reader can find the note or correction easily and quickly return to the primary text.

Signes-de-renvoi began as linking devices for corrections, particularly to supply material that had been omitted from the main text. From the tenth century onward, they were also used to link the main text to glosses and other types of marginal annotation. Throughout the rest of the Middle Ages, they were commonly used for both functions – correction and discursive annotation – but their use and form were never widely standardized. When print technology restricted the number of possible symbols to those in the fonts available to printers, and as the heavily glossed text became less normative in printed books, the forms and usage of signes-de-renvoi were greatly reduced – except in the case of alphabetical or numbered marginal annotations, which persist to the present day as footnotes Footnote note printed at the bottom of the page. See: Shoulder-Note Endnote Side-Note CLOSE or ESC and endnotes Endnote note printed at the end of a chapter or book. See: Shoulder-Note Footnote Side-Note CLOSE or ESC.

Manuscript History

Figure 2

Click For Larger Image

London, British Library MS Additional 43725 (Codex Sinaiticus), fol. 233r, col. a (detail). Image courtesy of The British Library Board.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 3

Click For Larger Image

London, British Library MS Royal 7.C.xii, fol. 105r (detail). Ælfric, Catholic Homilies. Image courtesy of The British Library Board.CLOSE or ESC

Signes-de-renvoi have their roots in early omission and insertion signs. In Greek manuscripts from as early as the first century, text that had been mistakenly omitted was supplied in the top or bottom margins and pairs of words and/or symbols directed the reader to the location where the supplied omission was to be inserted. E. A. Lowe found, in western European manuscripts of the fourth through eleventh centuries, a range of such signs, including obeli, asterisks, crosses, and other combinations of lines and dots. In the fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus, for example, a pair of arrow-shaped signs show where the missing words kakōs echōn ("being ill") should be inserted into the text of Luke 7:2 (see fig. 2). Early Latin manuscripts also used the abbreviations hd and hs (hic deorsum and hic sursum, meaning "here downward" and "here upward") to direct the reader to the top or bottom margins. The meanings of the hd and hs abbreviations were often not understood by later scribes, who nevertheless continued to use them as linking devices.3 For example, Insular (especially Anglo-Saxon) scribes from the late seventh century onward used d in the main text to link to h in the margin.4 When the directional meaning of hd or hs is not understood by a scribe and the abbreviation is repeated both in text and in the margin, the sign has been reduced to "a mere signe-de-renvoi."5 Signes-de-renvoi were first used in the same way as, and sometimes together with, the hd and hs abbreviations: that is, as linking devices to indicate an omission and insertion.6 Fig. 3 shows a pair of cross-shaped signes-de-renvoi used by Ælfric of Eynsham in an autograph manuscript of his Catholic Homilies to link missing text, supplied in the lower margin, to an insertion point in the main text block.

Figure 4

Click For Larger Image

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Auct. F.4.32 (“St Dunstan’s Classbook”), fol. 2r (detail). Image courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.CLOSE or ESC

Figure 5

Click For Larger Image

London, British Library MS Royal 6.A.vi, fol. 78r (detail). Aldhelm, De laudibus virginitatis, glossed. Image courtesy of The British Library Board.CLOSE or ESC

It was a natural development of the signe-de-renvoi to use it not only for omissions but also for other types of corrections, especially extensive ones. Minor corrections were most often performed interlinearly Interlinear written or printed between the normal lines of text. CLOSE or ESC, within the main text block; for example, a mistake could be erased and the corrected text written over the erasure or above the line. However, the medieval scribe always had the option of providing the correction in the margin and linking to it with a signe-de-renvoi,7 especially where there was not sufficient space for the correction within the main text block or where an inline correction might be judged too untidy. Though erasures and inline corrections were preferred, the signe-de-renvoi was the most common linking device for marginal corrections.8 If signes-de-renvoi provided a versatile and efficient way of linking marginal corrections to the main text, their function could be, and was, extended to other types of marginal annotation, such as explanatory glosses (scholia), supplementary texts, and extended commentary. From the ninth century onward, increasingly sophisticated scholarly books presented complex reading environments in which the main text might be elaborately glossed by the original or later scribes. In such cases, signes-de-renvoi provided an unambiguous method of linking commentary to specific points in the main text.9 For example, fig. 4 shows Latin and Breton glosses in the hand of the ninth-century scribe keyed to the main text by a wide variety of arbitrary symbols. A tenth-century manuscript of Aldhelm’s prose treatise in praise of virginity (fig. 5) uses alphabetical signes-de-renvoi for the glosses. Signes-de-renvoi also proved useful for any kind of supplementary text, such as the English text of "Cædmon's Hymn" in Bodleian Library MS Hatton 43, an eleventh-century copy of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum; an English version of the poem has been added to the bottom margin by a later scribe and linked to its Latin equivalent in the main text block (fig. 6).10 These applications of the signe-de-renvoi, supporting the complex activity of perusing glosses alongside primary texts, provided visual tools to facilitate what has been called "reference reading," searching a text for particular items of information.11

Figure 6

Click For Larger Image

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Hatton 43, fol. 129r. Cædmon’s Hymn as marginal note to Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum. Image courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford..CLOSE or ESC

Figure 7

Click For Larger Image

London, British Library MS Additional 54228, fol. 7r. Image courtesy of The British Library Board.CLOSE or ESC

Some texts that lend themselves to extensive commentary, such as biblical or legal texts, were designed to be annotated extensively and ample space was provided in the margins. Medieval manuscripts were often laid out in order to be glossed, for instance, by leaving very wide margins that a later glossator would be expected to fill.12 In the case of well-established commentary traditions such as the standard glosses on biblical books from the twelfth century onward, the association of text and gloss was usually accomplished by page layout Layout a plan for the appearance of a piece of printed work. See: PDF Page CLOSE or ESC, indexing systems, and rubrication instead of a linking system based on signes-de-renvoi, although symbols similar to signes-de-renvoi might be used to indicate citations.13 However, for corrections, occasional annotations, or readers’ comments, the signe-de-renvoi remained an important tool. This was the case even for non-scholarly texts: for example, fig. 7 shows an unusually elaborate series of signes-de-renvoi linking notes to entries in a list of rents from an English estate book of c. 1200. More unusually, signes-de-renvoi might link marginal images to words in the main text, as in the case of the illustrated troubadour lyrics in a thirteenth-century Italian manuscript, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M.819.14

Navigating Matthew Paris' Chronica Majora

Figure 8

Click For Larger Image

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 26, fol. iii R fld A (detail). Matthew Paris, Itinerary to Jerusalem, Chronica majora. Image courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.CLOSE or ESC

The itinerary maps at the beginning of Matthew Paris' Chronica Majora facilitate interaction. The maps associated with this thirteenth-century medieval chronicle have been described as an "imagined pilgrimage" for those who were not able to travel.15 The Cambridge MS of the Chronica Majora makes innovative and interactive use of a signe-de-renvoi in the prefatory maps. The sign bridges the gaps between elements of the manuscript that are not illustrated, such as the wide gaps of ocean or land that have to be imagined. The pages have extra flaps that can be unfolded to expand the surface of the page. According to Daniel Connolly, "this text also visualizes the route that has been lost in the working of the flap (that is, the route through Apulia). Here, however, that route is no longer a road or a series of cities; it becomes, at the dotted sign θ, a boat and its path through the Mediterranean – but not even a route so much as a sign of route making."16 Thus Connolly suggests that the sign symbolizes the mode of transportation from one city to another, and that the symbol was chosen to facilitate this metaphor and so to improve interaction.

Connolly explains how the dotted linking sign (θ) orients the reader and maintains a route through the map of cities. When the reader comes across the sign in the text of the itinerary, the corresponding sign by the image guides the reader through the visual elements (see fig. 8). When the text in the margin is oriented in such a way that the reader must rotate the page to read it, the sign is also rotated so that it is oriented correctly in relation to the image, helping the reader to determine which way to orient the page.17 Hence the sign in the Chronica Majora enhances interactivity, orients the reader, and suggests a metaphorical explanation for travel that creates a more immersive reading experience.

Print History

Figure 9

Click For Larger Image

Geoffrey Chaucer, Canterbury Tales (Wynkyn de Worde, 1498), STC 5085, sig. y1r. Image courtesy of The British Library Board.CLOSE or ESC

Many physical characteristics of the manuscript page Page one side of a leaf. See: Recto Leaf Verso PDF Pagina Layout Pagination CLOSE or ESC were adopted by print. Linking devices for annotations, including signes-de-renvoi (often called reference marks in print contexts), continued to develop in the production of printed books. However, whereas symbols used in manuscript annotation are potentially unlimited and often idiosyncratic, printed reference marks are restricted by availability and quantity of the types Type metal letters used in a printing press. See: Face Typeface Type-Founder x-height Ascenders Foul Case Galley Typesetter Type Case CLOSE or ESC in a printer's font. For this reason, linking symbols for annotations in print became much more standardized. Asterisks, daggers, and other symbols that were used in manuscript annotation and correction were often used as signes-de-renvoi in early print. For example, Wynkyn de Worde in his 1498 edition of Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales solved the problem of linking marginal glosses to the inner column of the prose Pardoner’s Tale by employing crosses as reference marks (fig. 9). However, de Worde's layout primarily relies, as did the medieval text-and-gloss format, on spatial proximity to guide the reader; the cross symbol he used as a linking device could not provide the precise one-to-one correspondence of a full system of signes-de-renvoi.

Figure 10

Click For Larger Image

Geneva Bible (1560), opening of the Epistle of Paul to the Ephesians. Image courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

Letters of the alphabet, which were sometimes used as signes-de-renvoi in medieval manuscripts, were unambiguous, ordered linking symbols available to printers, as were Hindu-Arabic numerals.18 The marginalia Marginalia anything appearing in the margins of a text, including printed and manuscript notes, and decorations. See: Margin CLOSE or ESC of the 1560 Geneva Bible (fig. 10), among the most widely read early modern texts, are iconic, and particularly instructive when looking at early printed annotation.19 Like many medieval Bibles, the 1560 Geneva Bible is full of marginal notes and commentary. For example, at the beginning of Ephesians, there are three types of annotation used on the same page: asterisks, a symbol for textual variants (“), and lettered marginal notes. These symbols distinguish different types of annotations. Asterisks and the alternate reading symbol (“) provide a quick note or cross reference, while lettered footnotes provide commentary. Elsewhere, two pipes (||) are used for alternate readings.

The two medieval functions of signes-de-renvoi in medieval manuscripts – correction and annotation – shifted in print environments. Early printed books might still be corrected by hand, but, by the sixteenth century, corrections were usually compiled in errata Errata a list of errors in the publication. Since errors could be found both throughout and after the initial print run, the presence of an errata list, and the number of items on it, can frequently be used to distinguish earlier from later impressions within an edition. CLOSE or ESC lists or incorporated into later print runs Print Run the number of copies produced in a single edition or issue. See: Stop-Press Cancel CLOSE or ESC.20 The practice of surrounding an authoritative text with glosses and annotations persisted into early modern print environments, however; thus not only could glosses and commentaries be printed around the main text block, but modern readers, like medieval scribes, continued to supplement their printed books with their own annotations.21 Scholars were also regular users of these types of marginal annotations, employing them for scholarly editions of texts and for their own commentary.

Such practices were common among humanist readers and were encouraged among Protestant readers of vernacular Bibles.22 William Sherman notes that in early printed commentary of Bibles, such as that in the Geneva Bible, "most marginalia were concerned with clarifying and digesting the text, making it easier to read and apply to particular (and often peculiar) needs."23 Annotation by readers was also a potential continuing use of signes-de-renvoi. Readers added their own clarifications and interpretations, but also added cross-references and other indexical signs to their Bibles. Annotations by readers were not always looked upon with favour by those who considered a lay-person’s comments a disservice to the Bible, but they were an important part of reading practices.24

Figure 11

Click For Larger Image

John Ogilby, Homer: His Iliads Translated, Adorn'd with Sculpture, and Illustrated with Annotations (London: Thomas Rycroft, 1660), Wing H2548, p. 1. Image courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.CLOSE or ESC

In the eighteenth century, during the notorious "battle of the books," this type of annotation became a subject of ridicule and satire. William Slights suggests that "readers had begun to object to such intrusions from the margins, not so much on spiritual grounds (though the furore over annotating Holy Scripture had raged for centuries) as on aesthetic and class snobbery ones."25 For example, the footnotes in Alexander Pope’s Dunciad Variorum (1729) parody the extensive footnotes of translators such as John Ogilby even as they lavish false praise on him for his editions of classics26 (fig. 11). Annotation came to be seen as the pedantic and excessive baggage of the printed page.27

Modern print continues to use text annotation, especially in scholarly and religious texts. Footnotes and endnotes are the usual form in modern print for this type of linking. Though the symbols are not as varied as signes-de-renvoi, they perform a similar linking function for modern readers, using characters already in sequence and readily available in type. In print environments today, the one regular function of a text-to-margin linking device that remains is to link main text to annotation.

Hyperlinks and Hashtags

Hyperlinks are obvious candidates when trying to determine a digital equivalent of the signe-de-renvoi. Online texts often use hyperlinks to connect citations and annotations to anchors in the main text, and these devices enable the exit from and return to a location in the main text. But similarities between the ways we engage footnotes and links in digital environments, and human interactions with signes-de-renvoi in a manuscript environment, depend on interface design.

Online linking is a machine-readable practice. Usually, a link is identified as a hyperlink by a difference in colour and/or a symbol that indicates that a link will be opened in another window, but after the user clicks on the link, the rest of the process is carried out in sequence by the user’s computer, Internet Service Provider, the host server, etc. Different navigation strategies produce different reading experiences. When a link directs the user to an anchor on the same page, the user must be provided with a means of returning to the previous location (or must use the "back" command in the browser). When exterior links are opened in the same window or another window or tab, the user must become oriented to a new page. This process is much different from that facilitated by signes-de-renvoi in purely visual, human-readable, and human-navigated manuscripts, which rely on the uniqueness of the sign on the page and on human intuition to connect two sections of content which are spatially fixed. The hyperlinks that most nearly resemble signes-de-renvoi are those that present supplementary content without requiring the reader to navigate away from the original location: for example, pop-up windows that appear on mouse-over require minimal movement of the hand and eye.

Symbols in digital environments that signal more content are also similar to signes-de-renvoi in the variety of their forms, from the icons in task bars, to downward facing arrows that signal drop-down menus, to information buttons (i) and icons that signal the presence of tools such as search functions. Icons are an efficient way of signalling additional content when the meaning of the symbol is understood. In digital environments, however, readers often train themselves to block out marginal content, which may be filled with advertisements and footnotes, such as the "small print" in Terms of Agreement.

Figure 12

Click For Larger Image

Screenshot of #signe-de-renvoi tweet, from Erik Kwakkel on Twitter, 11 June 2013. Image courtesy of Erik Kwakkel.CLOSE or ESC

Another close analogue of the signe-de-renvoi is the hashtag (#) (fig. 12). In long documents, page anchors are coded with a hashtag, followed by the name of the section title. Hashtags may seem similar to links and footnotes, but they have a wider variety of functions. Downloadable files or documents are assigned a hashtag string or Digital Object Identifier (DOI) so that they can be easily retrieved from multiple locations. In blogging and microblogging environments, hashtags can be used to group messages about specific content or comments and stories about a particular event. Hashtags expand on previous linking and cross-referencing, creating massive networks and associations in some cases, or helping to find a specific item in a large amount of data. The hashtag is user-generated with meaningful content, but it is treated as a metadata tag by the computer. The fact that it is human-readable as well as machine-readable makes it a digital analogue to the signe-de-renvoi in a text environment.28

Budny, Mildred. "Assembly Marks in the Vivian Bible and Scribal, Editorial, and Organizational Marks in Medieval Books." In Making the Medieval Book: Techniques of Production. Proceedings of the Fourth Conference of the Seminar in the History of the Book to 1500, Oxford July 1992, edited by Linda L. Brownrigg, 199-239. Los Altos Hills, CA: Anderson-Lovelace, 1995.

Carlson, David. "Nicholas Jenson and the Form of the Renaissance Printed Page." In The Future of the Page, edited by Peter Stoicheff and Andrew Taylor, 91-110. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Connolly, Daniel K. "Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris." Art Bulletin 81, no. 4 (December 1999): 598-622.

Connolly, Daniel K. The Maps of Matthew Paris: Medieval Journeys Through Space, Time and Liturgy. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009.

De Hamel, C. F. R. Glossed Books of the Bible and the Origins of the Paris Booktrade. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 1984.

Grafton, Anthony. The Footnote: A Curious History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Grafton, Anthony. "The Humanist as Reader." In A History of Reading in the West, edited by Gugielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane, 179-212. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1999.

Graham, Timothy. "Glosses and Notes in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts." In Working with Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts, edited by Gale R. Owen-Crocker, 169-71. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2009.

Hamesse, Jacqueline. "The Scholastic Model of Reading." In A History of Reading in the West, edited by Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane, 103-19. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1999.

Huot, Sylvia. "Visualization and Memory: The Illustration of Troubadour Lyric in a Thirteenth-Century Manuscript." Gesta 31 (1992): 3-14.

Jackson, H. J. Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Ker, N. R. English Manuscripts in the Century after the Norman Conquest. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960.

Kiernan, Kevin. "Reading Cædmon's 'Hymn' with Someone Else's Glosses." Representations 32 (1990): 157-74.

Lewis, Suzanne. The Art of Matthew Paris in the "Chronica Majora." Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Lowe, E. A. "The Oldest Omission Signs in Latin Manuscripts: Their Origin and Significance." In Paleographical Papers 1907-1965, edited by Ludwig Bieler, vol. 2, 349-80. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972.

McKitterick, David. Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450-1830. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Molekamp, Femke. "'Of the Incomparable Treasure of the Holy Scriptures': The Geneva Bible in the Early Modern Household." In Literature and Popular Culture in Early Modern England, edited by Matthew Dimmock and Andrew Hadfield, 121-35. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009.

Nichols, Stephen G. "'Art' and 'Nature': Looking for (Medieval) Principles of Order in Occitan Chansonnier N (Morgan 819)." In The Whole Book: Cultural Perspectives on the Medieval Miscellany, edited by Stephen G. Nichols and Siegfried Wenzel, 83-121. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Parkes, Malcolm Beckwith. "The Influence of the Concepts of Ordinatio and Compilatio on the Development of the Book." In Medieval Learning and Literature: Essays Presented to Richard William Hunt, edited by J. J. G. Alexander and M. T. Gibson, 115-41. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976.

Parkes, M. B. Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993.

Pope, Alexander. The Dunciad: with Notes Variorum, and the Prolegomena of Scriblerus. London: Lawton Gilliver, 1729. Edited by Allison Muri and Catherine Nygren at http://grubstreetproject.net/works/T5549.

Rouse, Mary A., and Richard H. Rouse. "Statim invenire: Schools, Preachers, and New Attitudes to the Page." In Authentic Witnesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts, 191-219. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991.

Rouse, Richard H. "Backgrounds to Print: Aspects of the Manuscript Book in Northern Europe of the Fifteenth Century." In Authentic Witnesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts, by Mary A. Rouse and Richard H. Rouse, 449-66. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991.

Rumble, Alexander R. "Cues and Clues: Palaeographical Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Scholarship." In Form and Content of Instruction in Anglo-Saxon England in Light of Contemporary Manuscript Evidence, edited by Patrizia Lendinara, Loredana Lazzari, and Maria Amalia D'Aronco, 115-30. Turnhout: Brepols, 2007.

Saenger, Paul. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Saenger, Paul. "Reading in the Later Middle Ages." In A History of Reading in the West, edited by Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, translated by Lydia G. Cochrane, 120-48. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1999.

Sherman, William H. Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Slights, William W. E. Managing Readers: Printed Marginalia in English Renaissance Books. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Slights, William W. E. "Back to the Future -- Littorally: Annotating the Historical Page." In The Future of the Page, edited by Peter Stoicheff and Andrew Taylor, 91-110. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Tribble, Evelyn B. Margins and Marginality. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993.

Tribble, Evelyn B. "'Like a Looking-Glas in the Frame': From the Marginal Note to the Footnote." In The Margins of the Text, edited by D. C. Greetham, 229-44. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.