Reliably Unreliable Climate

Western Canada did not discover drought during the Great Depression. There were other droughts in the years before and after the 1930s, even though the three prairie provinces were abnormally wet throughout much of the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Drought, both intense and prolonged, is actually the norm for the region, where evaporation exceeds precipitation on an annual basis.

The Hypsithermal Interval (also called the Holocene Thermal Maximum [HTM]), a period of centuries-long aridity, as long as four thousand years, held the region in a stranglehold from about 9000 to 5000 years ago during the Middle Holocene period. Average annual temperatures rose as much as three degrees Celsius higher than current values, while humidity and moisture levels decreased dramatically. The upshot was a general northward shift in the grasslands (based on an analysis of plant and tree pollen assemblages secured from ancient sediments). Over time, the Hypsithermal drove a dramatic shift from grassland to forest across the central part of the region. There were no longer any transitional parklands--just an abrupt change from one ecological region to another.[1]

There is an on-going debate whether the Hypsithermal drove humans and the bison they hunted from the interior plains. The poor range conditions, it has been argued, could not support millions of grazing animals; there was simply not enough forage for them. But whether the bison disappeared completely from the region for two thousand years is extremely doubtful, especially because the mountain-fed Saskatchewan River continued to flow and the zone of short-grass prairie probably increased. It is more likely that the herds altered their seasonal grazing patterns to deal with the drier conditions, as well as decreased in size in response to the reduced carrying capacity of the land. Evidence of human occupation has also been unearthed in the region during the Hypsithermal Interval.[2]

Even though the climate 2000 years ago came to more closely approximate the climate today, variability remained the defining characteristic–not simply from season to season, but also from place to place.[3] One writer has half-jokingly summed up the weather situation as “reliably unreliable.”[4] This idea of constant variability challenges the practice of dividing recent worldwide climate shifts into the Medieval Warm Period (sometimes known as the Medieval Climatic Anomaly), when the climate was notably warmer for about four centuries (1200 to 800 years before present), followed by the Little Ice Age, which marked some five centuries of cooler, unstable climate. These broad climatic patterns can certainly be read in the proxy data collected in western Canada. But ancient tree-ring sequences that capture growing conditions of the past few centuries, especially precipitation, also point to periods of warm climate, even severe, multi-year drought, during the so-called Little Ice Age in the prairie west. Nor were climatic conditions always the same across the entire region. Tree ring data indicate that some areas escaped drought, whereas other areas suffered. Variability is a defining feature of the climate from locality to locality and from year to year.

-

Breaking Sod

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend (1968) illustrates how newcomers prepared previously-unploughed land for cultivation. It also addresses the practice of pulverising top soil in the belief this would help conserve moisture.

-

Dust

This scene, also from Dustbowl Dividend, features images of the blowing soil that characterized the 1930s.

- Vance, R. E., A. B. Beaudoin, and B. H. Luckman, “The Paleoecological Record of 6 Ka BP Climate in the Canadian Prairie Provinces,” Géographie physique et Quaternaire 49 (1995): 81-98. In special edition: Paleogeography and Paleoecology of 6000 yr BP in Canada, ed. Hélène Jetté.

- B. Reeves, “The Concept of an Altithermal Cultural Hiatus in Northern Plains Prehistory, “ American Anthropologist 75, 5 (1973): 1228, 1237, 1246; W.R. Hurt, “The Altithermal and the Prehistory of the Northern Plains,” Quaterneria 8 (1966): pp. 110-11.

- M. Boyd et al, “Reconstructing a Prairie-Woodland Mosaic on the Northern Great Plains: Risk, Resilience, and Resource Management,” Plains Anthropologist 51, 199 (2006): 235-6.

- Candace Savage, Prairie: A Natural History (Vancouver: Greystone, 2011), 80.

What Went Wrong in the 1930s

Much of western Canada’s prosperity in the 1920s had been fueled by the sale of wheat on the export market. Now, on the eve of the new decade, agriculture was badly staggered by an economic-ecological one-two punch.

A severe drought placed a stranglehold on the short-grass prairie district and would not let go for the better part of the decade. Pronounced dry spells had always been a persistent feature of the prairies since homesteading began in the 1870s, but the 1930s were notorious for the number of consecutive dry years. The problem was compounded by the ploughing of semi-arid lands that should never have been open to grain production, while farming techniques at the time only exacerbated the situation by the heavy working of the soil.

Hot, drying winds scooped up loose topsoil and whipped it into towering dust storms that made outside activity nearly impossible. Darkness at noon was not uncommon, while churning soil piled up in deep drifts along buildings, fence lines or ridges–anything that stood in the way of the swirling dust. At the peak of the storms, hundreds of thousands of acres of land were literally blowing out of control, while millions more had been sucked dry of any moisture. Even in areas where erosion was not a serious problem, the withering heat stunted the wheat crop, preventing the head from filling out with grain. Some fields were so patchy that harvesting seemed a terrible joke. Total wheat production dropped during the decade even though farmers continued to plant a crop in the expectation that things would be better the next growing season.

Then, there were the insect infestations. Tens of millions of pale western cutworms, often mistakenly identified as army worms, munched their way across the land, devouring crops, stripping shrubs and trees, and laying waste to gardens. The wheat stem sawfly, as suggested by the name, chewed through the lower stem of the stock, causing the grain to fall over. The undisputed champion insect pests, however, were the grasshoppers, which flew in with the winds “in numbers beyond all calculation, even beyond the exaggerated genius of the yarn spinners of the prairies.”[1] There was no shortage of amazing stories about the hoppers–how their swarms darkened the sky, how they ate the clothes on lines, even how the guts from their squished bodies stopped trains. They made the drought conditions worse by destroying any plant cover.

No one at the time would have predicted that the nadir of the Depression would not be reached until 1937 when the drought extended its reach beyond the North Saskatchewan River and the region’s wheat kings produced the smallest wheat harvest in thirty years. By then, other parts of the country were already recuperating from the economic depression. It would take the Second World War to put Western Canada back on the road to recovery.

-

Impact of Drought

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend (1968) describes how various family members coped with the drought.

-

Pests

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend examines the insects and weeds that flourished in the 1930s and also addresses other environmental effects of drought.

-

Grasshoppers and Criddle Mixture

Entomologist R. H. Painter describes how Norman Criddle first developed the Criddle Mixture to combat grasshoppers by 1885.

-

Applying Criddle Mixture

Entomologist R.H. Painter describes his organization of Criddle Mixture baiting stations in Manitoba after the 1932 grasshopper infestation in that province.

-

Grasshoppers Remembered

P. Janzen describes how he organized the Criddle Mixing Stations in Saskatchewan to distribute poison to farmers to combat grasshoppers in 1933-34.

Life at the Lowest Common Denominator

Prairie agriculture was hit with a double whammy at the start of the Great Depression. International demand for wheat not only collapsed, but the price went into a free fall. Beginning in 1930, at a time when western Canadians farmers derived most of their cash income from wheat, the price tumbled to forty-seven cents a bushel and remained well below a dollar for the rest of the decade. The consequences were catastrophic for grain producers who helplessly found that they were losing money on any crop they were able to harvest.

The other problem was poor crop yields. In the naive belief that things would be better next year, producers continued to plant wheat to recoup their losses. But the prolonged drought made fields so patchy that harvesting seemed a terrible joke. Total wheat production dropped during the decade even though wheat acreage actually increased during the same period. In other words, more cropped land was actually producing less wheat. The 1937 harvest was particularly bad. Wheat production in Saskatchewan, for example, dropped to a stunning thirty-five million bushels, a paltry 2.5 bushels per acre. It was the smallest provincial wheat harvest in thirty years, the major difference being that the 1908 crop had been grown on less than twenty percent of the 1937 acreage.[1]

Many farm operations did not survive the decade. Nor were large urban centres spared. Because cities and towns acted primarily as agricultural service centres, businesses floundered, unemployment soared, and tax arrears mounted as the price of wheat went into a tailspin. Retail trade shrank, while per capita income declined. The prairie provinces became the most heavily indebted region by the end of the 1930s.[2]

In September 1934, two newspaper reporters toured by car the so-called “burnt out” area of the southern prairies and found that six consecutive years of drought had reduced life “to the lowest common denominator.” From Tribune, south of Weyburn, Saskatchewan, they reported, “Today many of the stores and shops are vacant, windows nailed up, people gone. There is scarcely a scrap of crop in the country.” But at the same time, no matter where the reporters went, they were constantly being assured by farmers that “the land is still all right. All it needs is rain.”[3]

-

Crested wheat grass

L.E. Kirk describes how he developed the Fairway strain of Crested Wheat Grass that eventually was used throughout North America as an important cover crop to stop soil erosion.

- Province of Saskatchewan, A Submission by the Government of Saskatchewan to the Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations (Regina: Government of Saskatchewan, 1937), 136, 148-9, 174-80.

- A. Lawton, “Urban Relief in Saskatchewan During the Years of the Depression, 1930-39,” unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1969, 43-50; J. W. Brennan, Regina: An Illustrated History (Toronto: Lorimer 1989), 102.

- D. B. Macrae and R. M. Scott, In the South Country (Saskatoon: Saskatoon StarPhoenix, 1934), 13, 18, 20, 23.

Relief

The once-vibrant rural communities of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta buckled under the weight of the Depression. Prairie families and homes suffered, while businesses that had existed since the founding of villages either collapsed or tried to stay afloat by providing government-funded relief aid.

Many destitute people, overcome by shame, had to screw up their courage just to ask for help. One woman remembered seeing her father cry for the first time when he filled out his relief application for food for his hungry children. It was as if he was signing away his pride and independence. Another person was afraid that her reputation in her home community would be sullied if her request for help ever became public. “I don’t know what to do. I hate to ask for help,” confessed Mrs. P.E. Bottle of Craven, Saskatchewan, “every one knows me around here and I’m well liked, so I beg of you not to mention my name. I’ve never asked anyone around here for help or cloths[sic] as I know them to[sic] well.”[1]

At the start of the Depression, the provinces provided rural relief, including agricultural support (such as seed, feed, and fodder), to try to keep families on the land and producing a crop in the event that international wheat prices bounced back. This aid was supplemented by the Red Cross, which solicited donations of fruit, vegetables, and other foodstuffs from other provinces and then arranged for carloads to be shipped to distressed areas by the railways free of charge. One of the unexpected bonuses was dried salt cod from the Maritimes.

Ottawa’s rigid adherence to the principle that relief was a local responsibility put western Canadian communities on the front line in dealing with the growing jobless problem. The challenge was particularly daunting for major cities, already hobbled by the large debt they were still carrying from the reckless over-expansion before the Great War.[2] Most communities introduced residency requirements to limit the number of people on relief roles. Others reduced assistance or tried to get families to start over again on pioneer farms in the parkland and southern boreal forest as part of a “back to the land” movement.

Governments also worked to provide accommodation for the growing problem of rural debt–both in the form of outstanding bank loans for farm land and machinery and mounting tax arrears. Debtors, for example, were given the opportunity to work out new arrangements with their creditors or alternatively, to apply for a debt moratorium.

- Quoted in L. M. Grayson and M. Bliss, eds., The Wretched of Canada: Letters to R. B. Bennett, 1930-1935 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1971), 112.

- A. Artibise, "Patterns of Prairie Urban Development, 1871-1950" in P. Buckner and D. Bercuson, eds., Eastern and Western Perspectives (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981), pp. 132-4.

Living Through Drought

The drought, the misery, and the hopelessness spawned all kinds of exaggerated stories, many of which have become legendary. Children, for example, reached school age before knowing what rain was or came running home in fright when they felt a drop of rain for the first time. Another was that parents decided whether to send their children outside by throwing a gopher up in the air; if the animal dug a burrow, then there was too much dust swirling around. Or there was the young baseball player who lost his direction while rounding the bases during a dust storm and was later found several miles out on the prairie.

There was no denying, though, that the drought and the accompanying dust storms had a profound impact on the rural population and its daily life. Mothers were known to put lamps by windows so that children could find their way home from school. Responsible for much of the domestic labour at this time, women faced a frustrating battle trying to keep the dust out of their homes, setting wet rags on window sills and hanging wet sheets over doorways. But it still managed to seep through, depositing a thick film on everything, like a layer of ash from a volcano. The memory of the drought and the dust-laden winds would haunt people for years to come. “It is a despairing thing,” remarked Etha Munro four decades later, “to watch your farm and pastureland die a slow death over a period of several years, each year getting drier and more hopeless than the year before.”[1] Another dust-bowl survivor painfully recalled, “The wind had a moaning sound, sometimes a high piercing sound, it made my head ache. The wind blew day and night for, I am sure, five years.”[2]

Some people sought solace in their garden–if it survived the drought--one of the few places where they could find pleasure and fulfilment in a world seemingly turned upside down.[3] But poverty took its toll. So too did the isolation since many farm homes could no longer afford a radio, telephone or newspaper. “There is a feeling that one has been shoved out of life,” mused “The Forgotten Woman” to the “Mainly for Women” pages of The Western Producer in 1934, “some call it a living death.”[4] Author Max Braithwaite, who was a Saskatchewan rural school teacher, saw in the faces of his students’ mothers “the same tired look of resignation...drought and cold and worry and childbearing had cast them in the same sad mould.”[5]

The drought even found its way into the period literature. “The sun through the dust looks big and red and close,” Sinclair Ross wrote in his classic novel, As For Me and My House, “Bigger, redder, closer every day. You begin to glance at it with a doomed feeling, that there’s no escape.”[6] Or as Edna Jacques put it less elegantly in “The Farmer’s Wife in the Drought Area,” one of her popular Depression poems: “The garden is a dreary blighted waste/The air is gritty to my taste.”[7]

- The Western Producer, 1 April 1976.

- Quoted in Wendy Wallace, “ ‘All Else Must Wait’: Saskatchewan Women and the Great Depression,” unpublished PhD diss., University of Victoria, 1988, 60.

- The Western Producer, 8 February 1934.

- C. Bye, “A Friend to Woman: The Prairie Farm Garden During the Depression,” unpublished paper presented before Graduate Symposium on Gender Research, 2003.

- Quoted in Wendy Wallace, “ ‘All Else Must Wait’: Saskatchewan Women and the Great Depression,” unpublished PhD diss., University of Victoria, 1988, 113.

- Sinclair Ross, As For Me and My House (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1957), 96.

- Edna Jacques, Drifting Soil (Moose Jaw: Moose Jaw Times Co. Ltd. n.d.).

The Response in the Fields

The prolonged drought of the 1930s did more than expose the inherent vulnerability of the western Canadian wheat economy. It also revealed the shortcomings of common agricultural practices, especially when rainfall was deficient for several consecutive crop seasons.

One of the most daunting challenges was how to arrest soil-drifting and promote water conservation in the drought-stricken short-grass prairie district. The response of the R.B. Bennett Conservative government was to create the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA) in April 1935. Although the emergency program was intended as a cooperative measure with the three prairie provinces, the federal government was effectively assuming control of the problem, committing almost five million dollars over five years. It fell to the new Liberal government, however, to continue to fulfill the legislation, and the prime minister was not keen. “It is part of the U.S. desert area,” Mackenzie King noted in his diary, “I doubt it will be of any real use again.”[1] But Jimmy Gardiner, whose Agriculture department was responsible for administering the temporary program, embraced the PFRA as the only realistic solution to the problems created by opening the area to dryland cultivation in 1908. In fact, in 1937, as the situation in the southern prairies worsened and the drought reached as far north as the North Saskatchewan River, Gardiner pushed through an amendment that empowered Ottawa to take land out of cultivation and create community pastures. Two years later, the act was made permanent, a recognition that ongoing management of the ploughed native grasslands was necessary to ensure the ecological integrity of the region.

The PFRA went hand-in-hand with the efforts of university and government agricultural specialists who teamed up with local farmers to devise new ways of cultivating the land while avoiding moisture and soil loss. While the community pasture program took some land out of production across the prairie west, the PFRA goal was better farming, not necessarily a reconsideration of whether grain production was realistic, let alone feasible. And it appeared that these efforts were paying dividends by the end of the decade when the rains returned and farmers enjoyed decent harvests. But the threat of drought was always there–no matter what new farming practices were introduced and adopted.

-

Dams and Dugouts

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend (1968) describes early efforts to conserve water on the drought-stricken prairies.

-

Noble Blade

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend explains the operation of the Noble Blade, a piece of machinery intended to help preserve soil. It also discusses other efforts to adapt farming to dry conditions, including trash farming.

-

Plowing technique

Asael Palmer describes how he wrote the 1935 Information Bulletins to farmers instructing them on the various techniques to stop desertification occurring on their lands.

-

Community pastures

Agricultural Scientist Baden Campbell describes how PFRA community pastures were established as a means of combatting desertification.

The Great Trek

Drought forced many prairie residents from their homes. As early as 1930, the news of normal rainfall in the districts north of the North Saskatchewan River encouraged farmers to abandon their land in favour of starting over again in areas where there was at least the chance of growing a decent crop. This out-migration picked up momentum once it became apparent that the drought had a stranglehold on the southern prairies. But leaving was never easy. Mrs. A.W Bailey, who traded the family farm south of Regina for a new home in the Bjorkdale district, recalled asking her husband to stop the truck before her former house passed out of sight. “In those few moments,” she wrote, “I got a lasting mental picture of the little home where my first babies were born. The house that had sheltered us from the snow and wind and dust storms would stand lonely and silent now, with the mice playing in the rooms and the frost cracking the flowered wallpaper...I closed my eyes and said a silent little prayer.”[1]

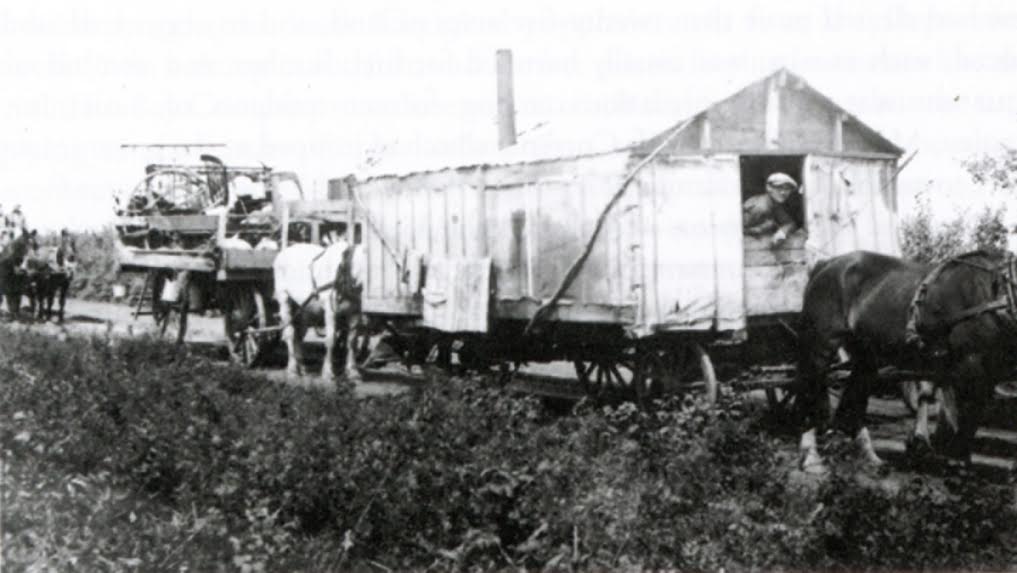

The refugees headed north with their worldly possessions in all kinds of conveyances, from heavily loaded trucks and horse-drawn Bennett buggies (cars with the motors removed) pulling small trailers, converted hay racks, or specially built cabooses often trailing a few cows. At night, there would be a string of campfires along the highways heading north, as families prepared meals and talked about their new homes and the future.

The migration north out of the dust bowl was no slow, orderly occupation of the land, but an invasion by anxious people intent on settling almost anywhere. “We just kept going along the highways and the trail,” explained A. Vaadeland of Lake Four village, just outside the southwest corner of Prince Albert National Park, “and then, at what looked like the last house, we just asked if the next quarter was empty. We felt certain we could make a go of this land.”[2] 45,000 refugees--representing about five percent of the provincial population--moved into the forest fringe of central Saskatchewan between 1930 and 1936. By the time of the 1941 census, the prairie provinces’ north had more people than at any other time in the past.

Those who arrived in the middle north in the early years of the 1930s usually secured the most desirable land, near the railway branch lines. But like the soldier settlers who moved into the same general areas a decade earlier, many of the new settlers survived on non-farm income, such as cutting cordwood, and ironically, continued relief assistance, to avoid starvation. The other, unexpected consequence of the great trek north was the hardship it brought local Indigenous populations. The new settler demand for local resources came at the expense of Indigenous peoples (including Métis) and their traditional reliance on hunting, fishing, and trapping.

-

Great Trek

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend (1968) illustrates how some drought-stricken farmers headed north in search of more prosperous farms.

-

Remembering Great Trek

G.P. Matte of the Northern Settlers Re-Establishment Branch describes how farmers abandoned southern farms and relocated with difficulty to northern areas.

The Climate History Legacy

In the spring of 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the prairie west as part of a national tour. It was the first time that a reigning British monarch had toured Canada, and nothing, certainly not the persistent rain, was going to prevent the region’s citizens from seeing the royal couple. More than one hundred thousand waited through light drizzle in Regina on May 25. Another forty thousand braved a heavy downpour in Moose Jaw. The rain did not deter the royals either. They insisted that activities continue as planned, even going as far as to ask that the top be left down on their car as they made their way through the streets in each city. The long-awaited break in the drought, coupled with the arrival of the king and queen, seemed a sign of good things to come.

But drought did not go away. Just as it had been a persistent feature of the prairie climate before the 1930s, drought returned to the region, sometimes for several years, during the remainder of the twentieth and first part of the twenty-first century. In fact, according to an Environment of Canada climatologist, the drought of 2002 was one of the worst on record for its severity.

The incidence of drought is expected to increase over the next century. Since the early 1960s, western Canada has experienced extensive and above normal warming. Temperatures across the region have risen by at least one degree Celsius, while larger increases (up by three degrees Celsius) have been reported for parts of Montana and the Dakotas. Minimum winter temperatures are also rising. This warming trend has also been accompanied by significant drying, leading to a steepening of the east-west moisture gradient during the twentieth century. Over the last 100 years, precipitation in eastern Montana and North Dakota has declined by ten percent while increasing by the same percentage in the eastern prairies.

Climatic variability has been recognized as the “new normal” for western Canada.[1] But drought is not new to the region; rather, it is the acceptance of drought as a regular and persistent feature that is new. And in the coming years, there needs to be acceptance of drought, planning for drought, and adjusting for drought.

-

Community Pastures

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend (1968) explains how community pastures were created in areas that were unsuitable for intensive agriculture.

-

Dustbowl Dividend

This scene from Dustbowl Dividend argues that the experiences of the 1930s led prairie farmers to adapt to local environmental conditions. It illustrates the mythology of the 1930s, which held that the lessons of this difficult period would ensure greater agricultural success in future. This was the dividend of the dustbowl years.